Translation Bureau launches ‘entry-level’ accreditation pilot, raising red flags for industry association

In a bid to expand its pool of interpreters, the federal Translation Bureau recently launched a new pilot project whereby it will offer contract positions and a new “entry-level accreditation” to individuals who came close but failed to pass its accreditation exam.

But the move is raising red flags with the International Association of Conference Interpreters (AIIC) Canada, which says the bureau is diminishing the quality of its services for a short-term solution to a long-term challenge: the shortage of qualified interpreters in Canada and around the world.

“We are watering down the qualification that’s required to uphold official language requirements under the act,” said Nicole Gagnon, AIIC Canada’s advocacy lead and a freelance interpreter with the bureau.

News of the pilot project was shared with different stakeholders earlier this spring, and the bureau confirmed it plans to begin offering entry-level accreditation to individuals in the near future once the results of the most recent May 10 accreditation exam—which 35 people sat—are known later this month.

The bureau has said these entry-level interpreters will only be assigned to cover “general, non-technical” departmental events, and not parliamentary ones. But Gagnon said AIIC Canada is concerned that once such individuals are “through that door,” in time, they will be used to cover parliamentary events as well, as the interpreter shortage “is not getting any better.”

“Near-pass candidates of the Translation Bureau’s accreditation exam will be granted partial accreditation to work as freelancers for the Bureau. This will allow the Bureau to contract these interpreters, who have demonstrated considerable interpretation skills, to cover general, non-technical events the Bureau would not otherwise be able to support,” explained Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC) media relations in response to emailed questions. The bureau falls under PSPC.

“Events being organized by other government departments will now be able to benefit from the Translation Bureau’s interpretation services instead of having to contract non-accredited interpreters on their own,” said PSPC, touching on the fact that due to the bureau’s struggle to meet current service-level demands, departments have had to look to outside providers to get interpretation services at some events.

“Parliamentary events are considered technical in nature and will therefore not be assigned entry-level interpreters,” stated the department.

The bureau has long offered interpreter intern positions to individuals who come close to passing its accreditation exam. These interns are hired as bureau staff, and while they cover parliamentary events, “they are constantly supervised, evaluated, and provided coaching to ensure the quality of their interpretation services,” the department explained. The number of interns hired depends on the bureau’s “capacity to offer an intern position, as well as candidates’ willingness,” said PSPC.

The new entry-level interpreters would be contracted as freelancers, and as such, PSPC confirmed there isn’t the same “employer-employee relationship” as exists with intern interpreters. Still, “coaching will be provided to the pilot project entry-level freelance interpreters, and they will be encouraged to take the exam to obtain full accreditation.”

PSPC said entry-level accredited interpreters “will remain in the Translation Bureau’s pool of freelancers in that capacity until” they either sit the exam again and get full accreditation, “quality checks show that they should no longer benefit from entry-level accreditation,” or until the bureau decides to end the pilot project.

“Entry-level freelance interpreters will be subject to quality evaluation of their work as are all Translation Bureau freelancers,” noted PSPC. “This being a pilot project, adjustments will be made as outcomes, lessons, and best practices become known.”

Last year, the bureau increased the frequency of its accreditation exam to two times per year. Historically, only a small fraction of the individuals who sit the exam actually pass, and not all who pass opt to work for the bureau.

For example, following the 2021 exam, nine of the 52 individuals who sat the exam passed, three of whom opted not to work for the bureau. No exam was held in 2020, but in 2019, just two people out of 44 candidates passed, only one of whom accepted an employment offer.

To try to boost capacity and entice more people to work for it, the bureau recently launched a new remote simultaneous interpretation—or dispersed mode—option, whereby freelance interpreters can work from outside the physical meeting room, and as a result are no longer required to live and work in the National Capital Region.

According to a slide presentation prepared by PSPC and shared with The Hill Times, entry-level accreditation would be equivalent to what’s called the “yellow quality index,” and such interpreters would be offered “one day of coaching per year, with feedback, by a Bureau staff interpreter.”

“Freelancers who wish to can contribute to the initiative by mentoring entry-level freelancers,” reads the slide.

The pilot has AIIC Canada—whose membership includes freelance interpreters—concerned on a number of fronts.

Along with worry that, once through the door, use of entry-level accredited interpreters will in time slip into parliamentary events, Gagnon highlighted the bureau’s own description of what a “yellow” rating means, and the understanding entry-level interpreters would only get one day of coaching guaranteed per year, with any other mentorship being volunteer based. Meanwhile, she said she understands the mentorship program for staff intern interpreters has already “suffered because … [of] the lack of interpreters to support them as they train.”

“How is someone who has failed an exam, who is going to work—let’s say—in general conferences, as claims the Translation Bureau, going to hone the skills required without mentoring—except for one day a year—to become a full-fledged interpreter?”

According to the definition included in the bureau’s open contract document for freelancers, a yellow rating is described as when “interpretation contains many inaccuracies or omissions OR the inaccuracies and omissions are more serious and affect the meaning OR linguistic mistakes and clumsiness are serious or frequent enough to distract the listener.”

“These people are not ready,” said Gagnon.

“The Translation Bureau is looking for a short-term solution to the problem of the qualified interpreters shortage, and there is no short-term solution.”

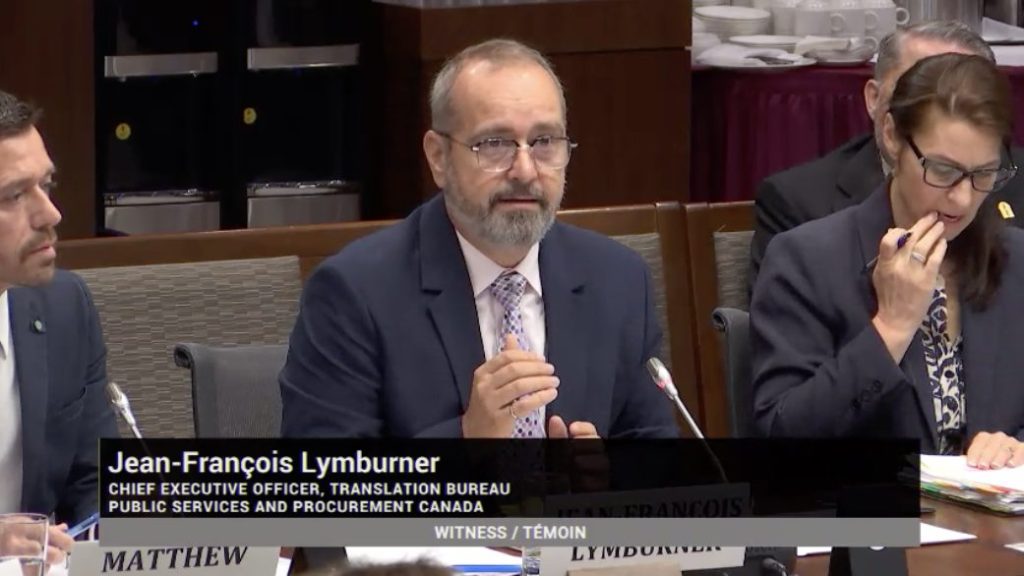

A June 10 open letter to bureau CEO Jean-François Lymburner signed by 101 accredited freelance interpreters spoke to the group’s “deep concern” over the bureau’s plan, writing that it “de-values the credentials” of accredited interpreters. The bureau’s “approach to addressing the shortage” of qualified interpreters “is both hostile to quality service and alienating of freelancers, to the point that a growing number of us will no longer be accepting assignments to work in Parliament.”

“With the increase in the number of accredited freelancers who have become disaffected from the [Translation Bureau], we know it is only a matter of time before this new group of non-accredited freelancers will be assigned to work in Parliament,” reads the letter. “Currently, accredited freelancers working at Parliament are assuming the lion’s share of the work on the Hill [55 per cent], but this number will drop with the introduction of the [bureau’s] plan.”

To be eligible for bureau accreditation, individuals must hold a master’s degree in conference interpreting. Currently, only two universities in Canada offer such a degree, producing only a small number of graduates each year. The bureau has previously noted efforts to encourage more universities to adopt such programs.

At a recent appearance before the Senate Internal Economy, Budgets, and Administration Committee, Lymburner noted “enrolment in language programs across the country has been declining.”

Touching on the idea of the entry-level accreditation pilot—which was not specifically mentioned—in response to a question about the use of “yellow category” interpreters, he said the bureau has focused on trying to use “lower levels [of qualification] in order to bring young people into the Translation Bureau earlier and support them.”

“I realize that this can give the impression that quality may be going down. However, that isn’t the case at all,” Lymburner told Senators.

According to numbers provided by PSPC, the bureau managed to keep up with staff attrition—albeit by largely slim margins—between 2020-21 and 2022-23, but last year only hired four new staff interpreters while five retired or left for other reasons. Currently, the bureau has 66 staff interpreters, and 84 freelance interpreters who provide services to Parliament.

In terms of freelancers, that’s a roughly 29 per cent decrease since 2020-21, when 119 freelancers were on the bureau’s roster.

AIIC Canada has warned of a “looming crisis” for the bureau when it comes to staffing levels. An August 2022 survey by the association found that, of the 92 accredited freelance interpreters who responded, 49 per cent indicated they planned to retire in the next five years.

Along with a scant pool of new grads and natural attrition, the bureau has been grappling both to respond to increasing service-level demands from Parliament, and to protect its existing workforce from injury.

When Parliament switched to a hybrid format amid COVID-19, reports of injuries among interpreters spiked. This led the Canadian Association of Professional Employees (CAPE), which represents staff interpreters, to file a complaint with the federal Labour Program in February 2022 alleging the bureau had violated its healthy and safety obligations under the Labour Code by failing to appropriately protect interpreters from the poorer sound quality associated with covering remote participants. In a February 2023 ruling, the Labour Program agreed with CAPE’s charge, and ordered the bureau to take steps to better protect its workforce. As part of its response, the bureau also created the position of director of parliamentary affairs and interpreter well-being.

While the rate of injuries has since dropped, reports continue, including from those interpreting in-person participants. In April, feedback caused by an earpiece device getting too close to a microphone led to a “significant hearing injury” for one interpreter, who went on leave as a result.

The Translation Bureau was allocated $35-million in the 2024 federal budget to help boost its translation and interpretation capacity, including $1.1-million over five years to establish a scholarship program.

Gagnon recognized the challenge the bureau is facing in increasing its workforce, noting “the association has no short-term solution, either,” but argued that with this new pilot project, it “is now trying to get through the back door to broaden” its pool.

“You have a great many interpreters who have been injured, you have a great many who have announced they will be retiring … this is not the answer, to take people who have failed the exam,” said Gagnon.

“The [Translation Bureau] was not mandated to water down quality. It has [been allocated] $35-million to grow the number of qualified interpreters, not to cut quality standards.”

Gagnon said the bureau’s focus should instead be on an “all-hands-on-deck approach,” with the government working together with industry and academia “to pull together to train the next generation of interpreters,” and encourage uptake of the profession, “not unlike what was done” to encourage more women to pursue careers in STEM.

“The government has to invest in training qualified people; you cannot do that overnight,” she said.

The Hill Times

LICENSING

LICENSING PODCAST

PODCAST ALERTS

ALERTS