Books, Big Ideas, Q&As

Natan Obed weighs in on the Major Projects law, Carney’s election, and what the North needs

As sovereignty worries push the government to “reimagine the space” in Canada’s Arctic, Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami president Natan Obed sees an opportunity to close the infrastructure gap facing Inuit communities.

“Our infrastructure needs are just categorically different than the rest of this country,” said Obed, who said he presented a list of 79 proposed projects worth about $31-billion over the next decade at a recent meeting with ministers.

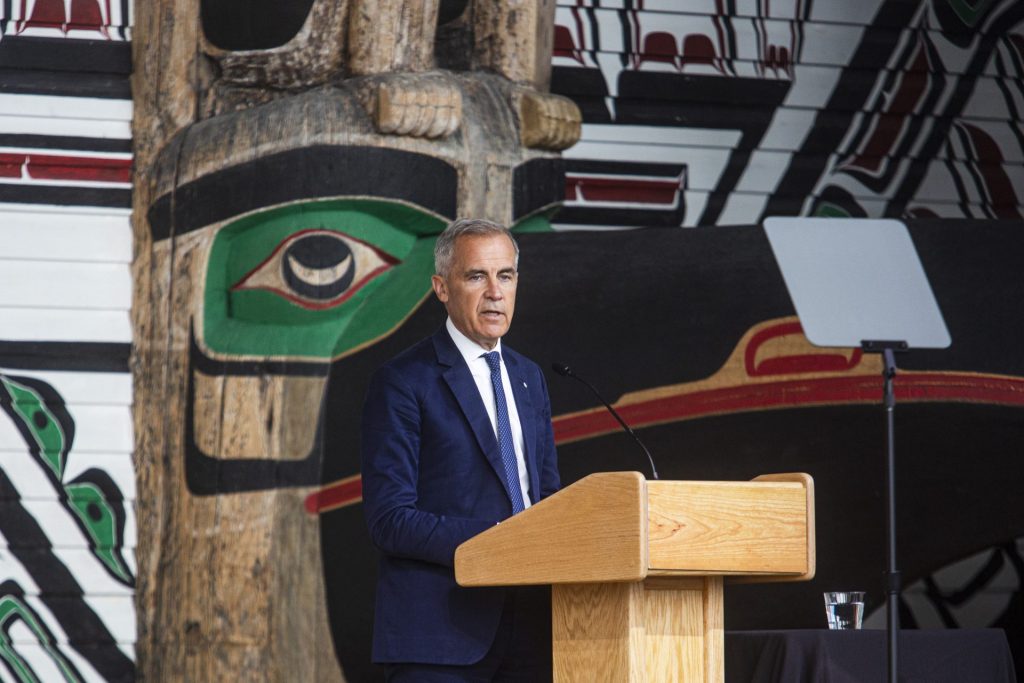

It’s part of the reason why Obed is opting to seek a fourth term leading the ITK after initially saying he wouldn’t re-offer. He said Prime Minister Mark Carney’s election played a role in his reconsideration.

“The ability to work with this prime minister and to know that there are huge opportunities on the table, and that reconciliation is still a key contributor to the thinking around the relationship motivates me,” he said in a recent interview with The Hot Room podcast.

The following interview has been edited for length, style, and clarity. Listen to that episode for the full interview.

You were part of a meeting with Inuit leaders, Prime Minister Mark Carney and a number of his cabinet ministers on July 24. How did the meeting go?

“I think the meeting went quite well. There was a lot of concern that Bill-C 5 and its implementation may be in conflict with our modern treaties or some of our existing regulatory processes that we’ve fought quite hard for over the course of the last 50 years. The prime minister put a lot of those issues to rest, and has promised to abide by our modern treaties and the way in which C-5 is implemented in the list of projects. We also got to work on a number of different areas as well, beyond just Building One Economy [Act].

“We talked quite a bit about the Arctic foreign policy and the implementation of that foreign policy, the Inuit child first initiative and other social initiatives, and really just a reset with this new government. And at the table there were no people who were at the last ICPC [Inuit-Crown Partnership Committee] meeting in November who were present at this meeting from the government side.

“All in all, I think it was great to have it in Inuvik. It got the ministers out of Ottawa, and it allowed for them to understand the challenges that we face every day in Inuit Nunangat but also from a social perspective. It’s always good for ministers and the prime minister to meet community members and to get a sense of what it’s like on the ground.”

When you say the prime minister promised to live up to his treaty obligations in regards to C-5, the law itself gives the government a tremendous amount of leeway to do as it wishes. What do we mean when we talk about the government has to live up to these obligations? What do you need to see from the government as it proceeds?

“Just on the interpretation of the legislation. We did a lot of work in the previous government to amend the interpretation act to create a universal non-derogation clause, and it lives within the interpretation act, basically stating that no legislation can derogate from the Government of Canada’s constitutionally recognized obligations to First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples. So our modern treaties fall under that. We are quite confident that when it comes to the priority or the precedent that this bill has limitations on its enforcement when it contradicts with our constitutionally-protected agreements.

“Now, practically, how the government implements its agenda and the tools that it uses to implement it, such as Bill C-5 or even the regulatory processes under our treaties, we are still trying to understand exactly how this will all unfold, what projects across Inuit Nunangat will be a part of the listed projects, and also we have larger infrastructure asks other than perhaps listed projects under this legislation. So a lot of time was also spent on discussing how to resolve the infrastructure deficit across Inuit Nunangat. That’s why it was really important for, say, the defence minister, to be there, as well, and to give a bit of perspective on what’s possible with dual use infrastructure that might be characterized as a military spend, but also will support infrastructure within our communities, as well.”

What kind of infrastructure do Canada’s Inuit need?

“We put a list forward of 79 projects over the next 10 years. Its total is about $31-billion. That’s a large number, and there’s a large number of projects. We have 51 communities. Only two of them are accessible by all weather road: Inuvik and Tuktoyaktuk in the Northwest Territories. The rest of the 49 depend upon air travel to get to southern Canada from our homeland, or even to travel between communities. There are no inter-community roads, either. There’s only one deep water port in all of our 51 communities, and that’s in an area that spans 40 per cent of Canada, and all of our communities are either directly in a marine environment, or adjacent through a waterway. So our infrastructure needs are just categorically different than the rest of this country.

“What I’ve said a number of times is we really need to bring Inuit Nunangat into Canada, and imagine this country and its infrastructure and equity in a different way than we have ever have before. I think the sovereignty defence and militarization pieces are all pushing the government of Canada to reimagine the space too, and so we, as ITK, are always fighting for the people to not be lost within the larger conversation.”

Dating back to at least the Harper government, references in the South to the North are often about sovereignty, about the idea of a military threat from Russia, or from China, maybe from the United States—that ships are threatening to elbow their way into Canada’s Arctic. Do the Inuit people who actually live in the high Arctic spend a lot of time thinking about that?

“I would say yes and no. There are many instances of foreign vessels being seen within our waters. In the research space, there is a greater interest from non-Arctic states to conduct and do research in Canada’s Arctic. From a resource-extraction perspective, there are a lot of other countries that hold mineral interests across our homeland—specifically China—in a number of scenarios. We know that these are a part of a larger political footprint and also the staging ground for what could be a pretty bitter dispute in the coming years around the Northwest Passage, and also the sovereignty of the Arctic. So we feel it and see it in different ways.

“We also know that we’re at risk because, say, at this very moment, we are largely dependent on Starlink for connectivity. There are other options, but Starlink has fast become one of the most widely used internet providers. Without connection through fibre-optic cables, we’ve solely dependent on satellite internet, and many cases, it’s generations behind when it comes to the ability for us to utilize that. I give that example because we are dependent, sometimes on private corporations or other nation states in order to just live sustainably in the Canadian Arctic, and it’s something that I don’t think is lost on CSIS [Canadian Security Intelligence Service] or on the minister of defence, but as a country as a whole, I don’t think that there’s been much attention paid to it. In our homeland, we think about this more often than not, especially since our families are in Greenland, Alaska, and the Chukotka region of Russia, each with their own political realities and turmoil.”

You recently confirmed that you plan to run for re-election as the leader of the ITK. That’s next month. You’d previously said you wouldn’t be running again. What changed your mind?

“Last fall, when the Trudeau government was in its dying days, it just seemed like on the horizon there was a lot of uncertainty in Ottawa and the leadership within Ottawa. It was quite clear that there was going to be a new prime minister, perhaps a new party running government. And also at the time after the election in the United States, with President [Donald] Trump re-emerging as a volatile actor, especially with the U.S.’s sites on the Circumpolar Arctic, but Canada as well, I thought that I still had a contribution here and a lot of new work on the table that seems to me to be urgent and of national interest. I now am a veteran of 10 years of this work, and I just had reconsidered about the role that I should or could play in Inuit politics. So I thought a lot about this, but in the end, we’re living in a pretty dynamic time, and the continuity that I can bring, I hope, will be appreciated by Inuit and by those who will elect me.”

Did Mark Carney’s election win play into that decision?

“Yes it did. The ability to work with this prime minister and to know that there are huge opportunities on the table, and that reconciliation is still a key contributor to the thinking around the relationship motivates me. It allows for me to imagine how the work will all transpire and how it will happen. It wouldn’t be that I would abandon my post if there was somebody, perhaps, who is less likely to be engaging and supportive. But at the same time, I think all of us, when we see a new opportunity that materializes, sometimes it reinvigorates us to double down and continue to do the thing that perhaps we were drifting a bit from.

“I’ve always been passionate about representing Inuit, and that hasn’t been the consideration. The consideration really was, how long should any one person be at the helm of the national Inuit organization? So I understand that my asking for another term is a departure from what I previously said. It also means that I will, at the end, have served for 14 years, but I feel like I’ve always led with a respect for all positions, and that I’ll continue to try to do that if re-elected.”

What’s left on your to-do list at ITK if you are re-elected?

“Well, there’s always the piece of unity and creating more unity within the Inuit regions. We are held together by our one society, but we are pushed apart by our different governance and our different relationships through treaties with the Government of Canada and our geography. So there’s always a standing issue that, in my mind, of building unity and keeping unity. And that is, for a population of about 70,000 people, our biggest asset when we come to the table in Ottawa. When ITK deliberates and passes resolutions, and I bring those forward to decision-makers, they can be certain that they’re hearing directly from Inuit.

“The other big pieces are ones of social equity and building a more sustainable society and a more prosperous society. Our vision here aligns with the vision of this government for building prosperity. How we do it is, is unique, I would say, and one that I would like to be a part of, not only conveying the need for distinctions-based work or specific Indigenous work, but also then the how—trying to figure out programs, policies, initiatives, and opportunities to ensure that Inuit across our homeland not only are able to thrive and do better, but also in turn, that it creates more prosperity for Canadians as well.”

The Hill Times

LICENSING

LICENSING PODCAST

PODCAST ALERTS

ALERTS