Books, Big Ideas, Q&As

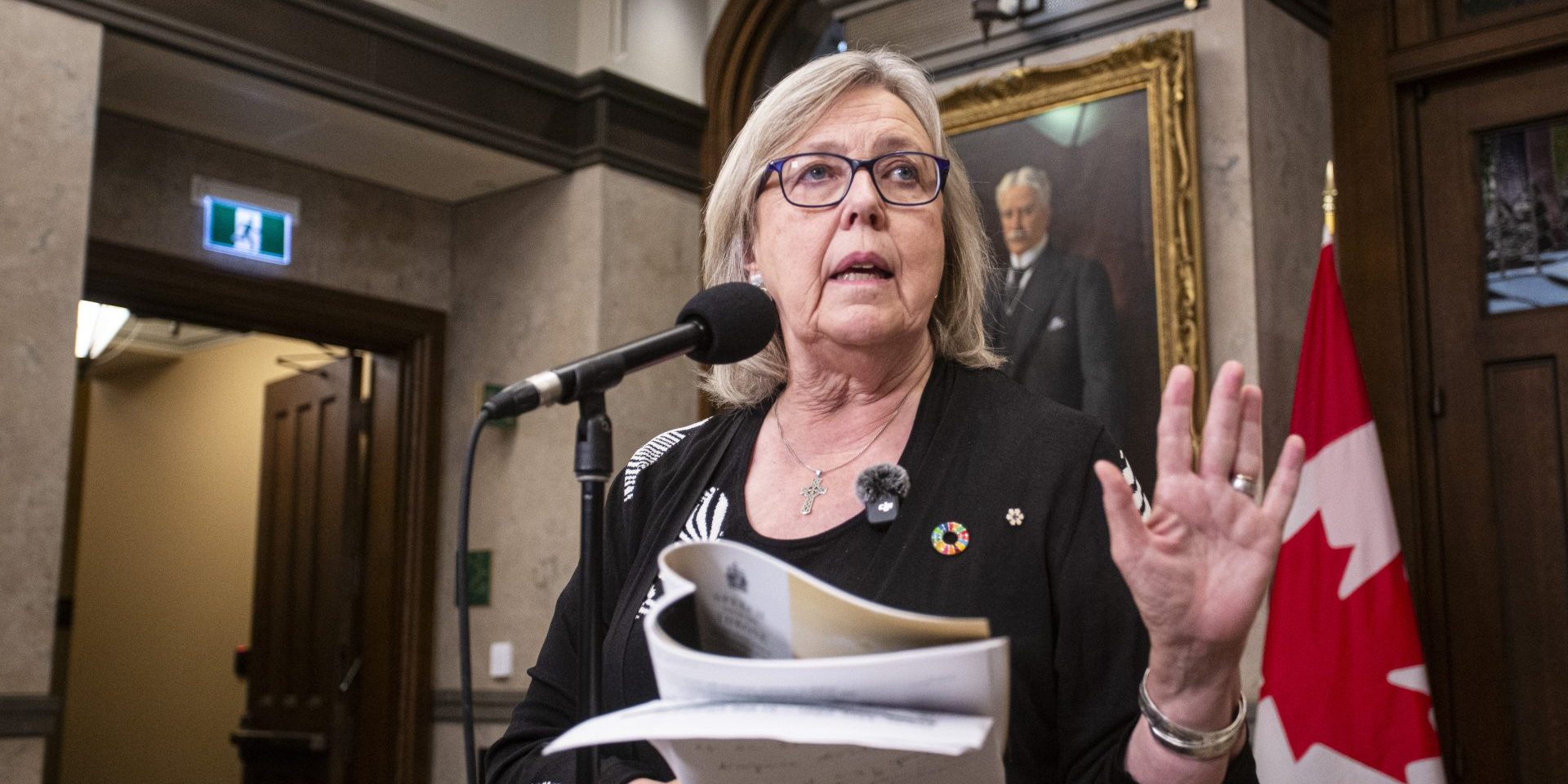

Q&A | Elizabeth May on Carney’s major projects’ ‘get-out-of-jail-free card’

Prime Minister Mark Carney’s proposed major projects legislation is styled as a “get-out-of-jail-free card” that is “trampling” on Indigenous and environmental rights, says Green Party Leader Elizabeth May.

In a recent episode of The Hill Times’ Hot Room podcast, May (Saanich-Gulf Islands, B.C.) raised concerns about Bill C-5 and the speed at which the government is trying to pass legislation that would skip major infrastructure and natural resource projects past the federal environmental assessment process if they make the list of “national interest projects.”

Prime Minister Mark Carney’s (Nepean, Ont.) government introduced Bill C-5 on June 6, and before the House of Commons debated it, his team had already introduced a motion to fast-track the bill, crunching Parliament’s time to study, debate, and vote on the law.

“It’s a very unusual piece of legislation. I’ve never seen anything like it,” said May, who has been scrutinizing Canada’s environmental assessment laws for decades.

“Carney’s bill is 100 per cent about unfettered political discretion exercised by cabinet.”

The following interview has been edited for length, style, and clarity. Listen to that episode for the full interview.

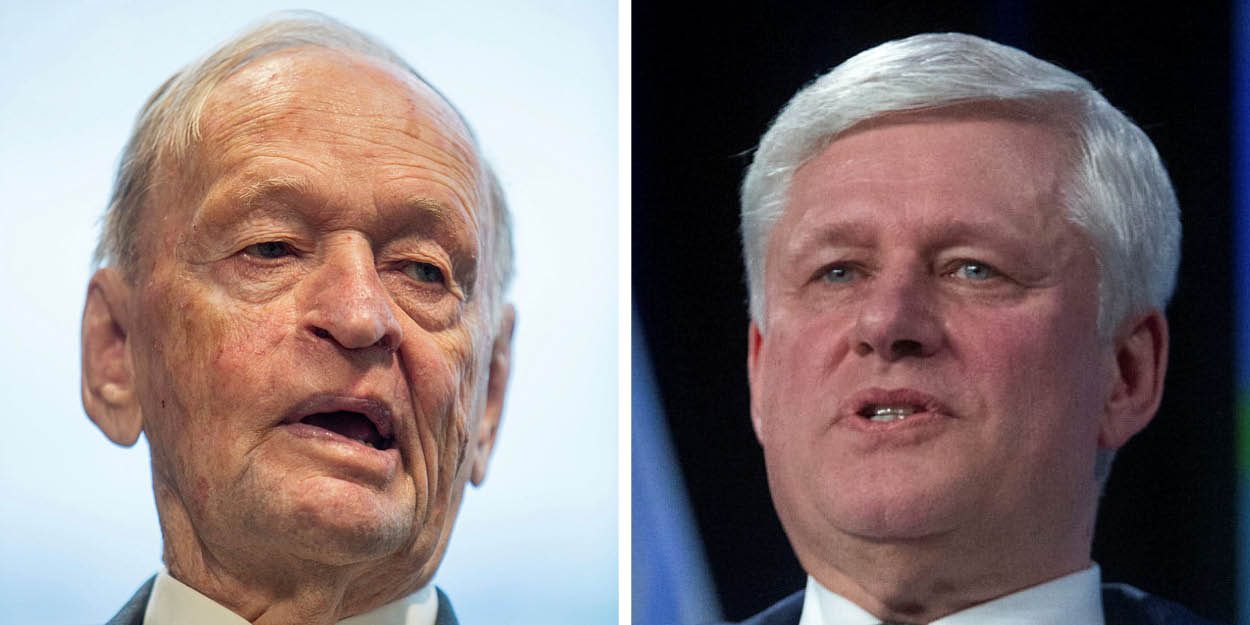

Let’s set the stage: In 1992, Brian Mulroney brings in an environmental assessment law that you worked on. Then, in 2012 Stephen Harper repeals that, and brings in his own. In 2019, Justin Trudeau brings in his own. It’s 2025, and we’re kind of doing this again. Why can’t governments get this right?

“They got it right in the 1980s, 1990s, throughout the 2000s. It wasn’t until Harper introduced the concept of deviating from everything that had gone on for the previous 40 years—of having very strict criteria, and if a project fell within those criteria, it was a fact-based, evidence-based decision. This project is either going to be reviewed federally or it’s not. And the question wasn’t about the project or the kind of project it was. It was clearly about what’s in federal jurisdiction. Ironically, Harper’s repeal of Mulroney’s law and the subsequent focus of Harper on ‘let’s have a list of projects that we’re going to review’ with no anchor to federal jurisdiction—that [Trudeau-era former environment minister] Catherine McKenna kept—that piece of legislation led to another important event on that timeline, which was the Supreme Court finding the federal government had exceeded its jurisdiction. That’s because of Harper’s decision that this should be a political discretion

“The essence of federal environmental assessment, when we get it right, is that different orders of government have a responsibility within their own area to ensure that from an environmental and also social point of view, a project has been reviewed. Harper changed that, and the Liberals kept Harper’s changes, and that’s why the court found that they’d exceeded federal jurisdiction.

“Carney takes it to a new height of political discretion, untethered, unfettered by anything. So this is an entirely new proposal. It is very time limited. This bill will exist for five years, but I think Mr. Carney should think twice about giving this kind of wide open political discretion to potentially a different government and a different prime minister. I’m not thrilled to have any government or any prime minister have unfettered discretion at this level, but we’ll see. Meanwhile, it’s not really an environmental assessment law. It’s another animal.

“Carney’s bill is 100 per cent about unfettered political discretion exercised by cabinet.”

Carney and his ministers are talking about ‘one project, one review,’ about getting projects approved within two years or less if they’re in the national interest, that Carney wants to make this a part of a plan to make Canada an energy superpower.

Let’s look at what the bill actually proposes. The Building Canada Act is just one half of government bill C-5. The other half of the bill has to do with lowering barriers to free trade between the provinces and territories. Is there any chance that the Speaker of the House could split this bill?

“Yes, of course, but depends. Part one is about trade and mobility between provinces, mostly about labour mobility and standards. Serious concerns have been raised about part one from the Canadian Cancer Society, and they really want the media and public to pay attention to their concerns that part one of the bill could lead to a race to the bottom on standards that protect human health against carcinogenic chemicals. Let’s set that aside.

“Part two is essentially an omnibus bill that is about projects in the national interest. So you could say it’s an environmental-assessment law. It’s basically trampling environmental assessment and trampling Indigenous rights if you have a political discretion and a political decision from cabinet without any mandatory criteria at all, that a project is in the national interest. So that decision will be essentially unreviewable by courts. I used to practice environmental law. What you look for is, here’s the legislation. Courts don’t second guess governments, but judicial review is to the extent of saying, ‘Did the minister follow the law?’ In that sense, part two of Bill C-5, the Building Canada Act, there’s no way to find that any cabinet didn’t follow the law because the cabinet has free reign to decide anything it wants without regard to any other mandatory considerations. It lists a bunch of factors, but … if a clause says so and so may consider the following that means they also don’t have to.

“If you’re not looking for ‘is this reviewable by the courts,’ and you’re looking at it from a public relations point of view, it says all the right things, but the things it says are of no legal consequence for the most part.

“Basically from the late 1990s throughout the beginning of this century, we had, as a country, resolved one project, one review, with joint reviews, so that you didn’t have a separate review in B.C. and a separate review federally for a project or Nova Scotia. We didn’t have duplicative, sequential reviews of projects, although you’re looking at the political rhetoric around it, particularly from Conservatives, you’d swear that you never got through the review process at one project, one review has been pretty much the norm.

“Back to what does Bill C-5 say: It doesn’t mention one project, one review. It doesn’t even suggest what you do—which most bills would—if there’s been a provincial decision or a provincial assessment is underway. There’s also nothing in Bill C-5 that says our process, start to finish, has to take two years. There’s nothing in Bill C-5 that says you can’t say a project is in the national interest unless you have consensus. Bill is silent as to any of those concepts.”

The bill says if the governor-and-council “is of the opinion” that a project is in the national interest, then the cabinet may add this project to the list of those that are in the national interest.

So what does the law say about how the cabinet decides whether it’s in the national interest? Subsection six says the cabinet “may consider any factor it considers relevant.”

“Does it say ‘you must consider these things?’ No. Cabinet may consider factors. You could have cabinet make a decision—it’s completely consistent with the language used in C-5—where the only thing cabinet looks at is recent polling.

“In terms of statutory interpretation, if you want something to be enforceable, it will say ‘shall.’ If it says, ‘may’ well they might think about it, including factors like chance of success of execution, importance to the economy, advancing Indigenous rights. This requirement uses weasel words even around the requirement to consult. But the requirement to consult has nothing beyond the usual federal requirements to consult—which have despite the fact that Speech from the Throne says everything we’re going to do is going to be deeply embedded in free, prior, and informed consent—nothing in C-5 suggests that free, prior, and informed consent will be respected.”

What does consult mean?

“Many, many times these issues have been brought to court. The reason that, at various stages, the TMX pipeline was found by the Federal Court to have violated Indigenous rights was because the consultation wasn’t meaningful. But it doesn’t say “meaningful consultation” in the bill, it just says consult. And there’s lots of other examples of consultation. Ministers must consult each other. And the cabinet has to consult various regulatory energy agencies. And the regulatory energy agencies are the only place where they have a veto, so consulting provinces isn’t even in there.”

“First Nations, if their Sec. 35 rights may be impacted by the project, they have to be consulted. But the quality of that consultation isn’t defined—other than previous court decisions. Certainly UNDRIP [United Nations Declaration on the. Rights of Indigenous Peoples] isn’t mentioned. I mean, within the environmental law community, it looks as though this is going to suspend environmental laws if they might get in the way once a project is on the list as a project of national interest. Ditto, First Nations, Métis, and Inuit rights can be pushed to one side if the project is on the special fast track. But again, the timing of the fast track isn’t in the law either. It’s a very unusual piece of legislation. I’ve never seen anything like it. It’s more like sort of a get-out-of-jail-free card that you win, like a game show, more than a piece of legislation.”

What is the downside of empowering a minister, a prime minister, to just hit the rubber stamp get these things done?

“What we’re going to get now is, I think, going to potentially slow projects down. Because there are such things as rights. Particularly the rightsholders in these scenarios are First Nations, Métis and Inuit. And then there’s also previous jurisprudence around what kind of decisions can be made without offending environmental assessment and previous determinations of the courts of what’s required.

“[With Bill C-5] There are so many question marks about the content of the bill. It offends every element of procedural fairness in the Parliament of Canada to imagine this bill can be pushed through before we adjourn for the summer. I’m prepared to sit so that we continue to have, or start having, any discussion of this bill, and how it will work, and what its impact is on Indigenous rights, environmental protection, or meeting our climate targets. Those are all wide open questions.”

The Hill Times

LICENSING

LICENSING PODCAST

PODCAST ALERTS

ALERTS