Books, Big Ideas, Q&As

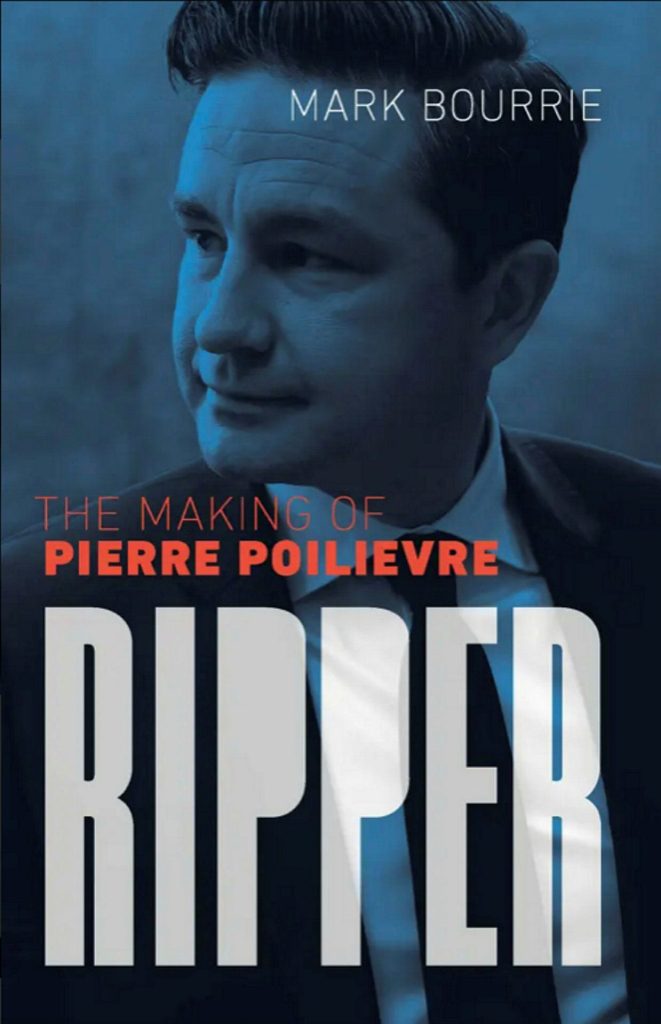

Poilievre is a ‘classic political ripper,’ says author of new bestselling biography

Mark Bourrie says he wanted to write a book about federal Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre because he saw a need for a biography that focused on Poilievre within the modern media environment in Canada. He also wanted to look at the rise of the right in Western democracies, and the undermining of this country’s democratic institutions. The result is Ripper: The Making of Pierre Poilievre, Bourrie’s 430-page, gripping, and exhaustive look at one of the more controversial leading figures in federal politics today. The book is detailed, well-written, and is currently on The Globe and Mail’s bestselling Canadian non-fiction books list.

Bourrie, who is a lawyer, author, former Hill journalist, and a historian, has written numerous non-fiction books, including Bush Runner: The Adventures of Pierre-Esprit Radisson, which won the prestigious RBC Taylor Prize for non-fiction in 2020. He is also author of Crosses in the Sky: Jean de Brébeuf and the Destruction of Huronia; Big Fear Me; The Killing Game: Martyrdom, Murder and the Lure of ISIS; Peter Woodcock: Canada’s Youngest Serial Killer; and Kill the Messengers: Stephen Harper’s Assault on Your Right to Know.

Bourrie argues that Poilievre is “a ripper,” a politician “who sees politics as a war that gives their lives meaning,” and says rippers make “fantastic opposition leaders,” but “awful” prime ministers.

This Q&A, conducted via email, has been edited for length and clarity.

How long did it take you to write this book? “I worked on it from late May or early June 2024 until late February 2025.”

Where do you write and what is your writing process for writing big biographies? “I write at home. I buy every book that I think will be relevant, then normally use Library and Archives Canada for research. With the Poilievre book, I got a lot of material at the Ottawa City Library, which gives people access to huge, expansive media databases. I also use university online academic databases (though they weren’t that useful in this project.”

What were your sources of information (documents, books, newspaper stories, reports), and why did you decide not to interview people? “I’m trained as a historian. I found the written record to be much more useful and accurate than interviews. Poilievre is a polarizing figure in ordinary times. By the time I started the project, he’d been leader of his party for almost two years and we were, supposedly, 18 months away from an election. Finding anyone in Ottawa who was non-partisan and fair was almost impossible.

“People who didn’t want him to win really didn’t want him to. I would spend hours listening to hours of rumour and come away with nothing usable. On top of that, there was a strong element of fear, especially in the media. I realized few people in Ottawa really know him. All this confirmed my bias against oral history. Poilievre’s life is well-documented. He’s been in the media spotlight since high school, and an MP for 21 years. I’m very comfortable with the written record. A lot of it was created before people became so polarized.”

Why did you want to write this book? “In 2016, I wanted to follow up on books about Stephen Harper’s information control and ISIS’s use of the internet as recruiting and communication tools. I hoped to start a book about the changing media environment and the creation of alternate media universes, but, at the time, no publisher was interested. Then I pitched a book about foreign use of the internet in asymmetrical warfare against Western democracies. No takers there, either. A proposal for a book on Pierre Radisson from 2004 was still kicking around and was picked up by Biblioasis, a boutique publisher that hadn’t handled much non-fiction. So I did that.

“The book sold well and won a prestigious prize. That allowed me to do another project that had been on my mind for years, a biography of Globe and Mail founder George McCullagh. It allowed me to delve into modern anti-democratic thinking in Canada. I also did a legal text for journalists for a law book company, and a biography of the Jesuit mystic Jean de Brébeuf. I’d never intended to be a biographer, but I’ve realized you can use biography to make important points about politics and society. They’re an awful lot of work, though, if you are serious about doing them well.”

Why did you want to write a book about Pierre Poilievre, specifically? “I believed there was a need for a book that centred Poilievre within the modern media environment in Canada and, to a lesser extent, the rise of the right in Western democracies. I’ve been concerned for a long time about the undermining of democratic institutions in Canada. [Former prime minister] Paul Martin tried to address what he rightly called the ‘democratic deficit,’ but politicians and the media lost interest when Paul Martin lost to Stephen Harper.”

Why is this book important, and who should read it? “Everyone should read it. What else would I say? The book is as much about the failings of modern political parties and the Canadian media as it is about Poilievre. It’s a warning that political parties are no longer democratic organizations where like-minded people can debate policy, develop local followings, and run for office to represent the interests and values of their regions.

“They’re election-campaign machines that are run by long-established cliques designed to elect whipped MPs to Parliament while ‘The Centre’ of unaccountable staffers and ‘strategists’ who propelled the leader forward takes real control of the country’s administration. This has been happening for 40 years, in both major parties, and it is killing democracy. It’s even worse here than it was in the United States. Though there, they now have a fascist in power who has no use for democracy and would get rid of it if he could.”

Why was it important to publish this book now in the midst of an election campaign? “It wasn’t published in the midst of the campaign. It came out before the campaign started. We had planned for a late April or early May launch, with the late spring and summer to promote the book. By the start of the fixed-date election campaign, the book would have had most of the media coverage that it was going to get, and it would be around like, say, Stephen Maher’s book on Trudeau (which I expected to be out in paperback by then).

“In the summer of 2024, I believed Justin Trudeau would be the Liberal leader and we’d go to the polls when we were scheduled to. Launching the book early to get it out before a spring election was not part of a plan, and it was bad for the book. Once the election was called, the CBC—the one media organization that can make a book a success—dropped its invitation for a major interview and the discussion of the book was caught up in the campaign.”

As the book’s title says, you argue that Pierre Poilievre is “a ripper,” a politician “who sees politics as a war that gives their lives meaning.” The entire book argues this quite forcefully, but can you explain here why Poilievre is a “ripper,” and not a “weaver”? “Rippers are fantastic opposition leaders. They find real and imagined scandals, force governments to defend policies, raise new issues, and are always challenging the status quo. Poilievre is a classic political ripper. So is Charlie Angus of the NDP. The Liberal Rat Pack were also pretty good rippers back in the day. The media has a few rippers who make important contributions to politics.

“Poilievre takes it farther by personalizing his attacks. Rippers, however, aren’t good at developing policy, partly because they don’t tend to socialize well, and they don’t get the rush and quick political results that come from a tough attack. Weavers, on the other hand, get gratification from developing policies and putting together coalitions. I think Justin Trudeau has the empathy of a weaver, but not the organizational skills. Right now—and surprisingly, at least to me—Doug Ford has become the most vocal weaver in Canada, at least on the issue of saving our sovereignty.”

New York Times columnist David Brooks was the one to first categorize between “rippers” and “weavers.” Why did this column resonate with you, and did this inspire you to write the book? “It didn’t inspire me to write the book. I saw Brooks’ model as a way to explain Poilievre in a simple way. I wrote the book because, in the spring of 2024, I believed Trump would be back, [Nigel] Farage would gain ground in the U.K., [Geert] Wilders would continue to be at the centre of power in the Netherlands, [Viktor] Orban would keep his lock on Hungary. A neo-fascist was on the verge of power in Austria, a fascist had the Italian premiership, the AfD was the most dynamic party in Germany, and the hard-right was making big gains in France.

“I believed then, and I still believe, we are in the early stages of an anti-democratic revolution in the West.

“Democracy in Canada was already in a sad state at least in terms of real public participation and even interest. A Canadian government that made common cause with that movement would be a disaster.”

Can “rippers” be good prime ministers, and has there ever been a “ripper” prime minister in Canada? “No. They’re awful. We’ve had two already: Arthur Meighen and John Diefenbaker. Meighen’s nastiness doesn’t show up in the history books because he never really got a chance to do much. He finished Robert Borden’s term after the First World War and served a few weeks after the King-Byng affair, losing the 1926 election. You have to dig deep into the politics of the time to see how hard he was, and how he scared people.

“For example, in the mid-1930s, the Ontario Liberals and Conservatives came up with an admittedly strange plan to form a coalition provincial government to try to deal with the problems created by the Great Depression and to stop the spread of unions into Ontario factories and mines. Meighen, who was a Senator at the time, crushed the proposal in one meeting.

“Diefenbaker was a great opposition leader. He was a brilliant, compassionate lawyer. But he had no ability to tolerate anyone who disagreed with him or to listen.”

How do you think Poilievre’s style of politics has affected and changed federal politics today? “Poilievre has made the never-ending campaign a real thing. I’m not sure that could continue through four years of a majority government, but I expect it to be normalized when we have minorities. It puts the prime minister at such a disadvantage since the PM’s administrative work and security concerns prevent that much travel. This kind of politics requires a huge amount of fundraising and organizing. We could see the House of Commons become even more of a prop and less of a democratic institution where MPs debate about proposed laws and use committees to examine policy and administration.

“The bigger change is in the development of pseudo-media to replace what used to be the mainstream media. Poilievre and his campaign were always miles ahead on creating their own ‘news’ content on platforms like YouTube, and partnering with partisan organizations that run outlets that produce what can best be called propaganda disguised as news and analysis.”

What were some surprises you learned about Poilievre? “I’m amazed at his drive, his luck, his determination. I was also surprised at his rigidness. He’s not a stupid man at all.

“I think he gives very little thought to policy. He just scans the political environment, looking for things that will sell. That could change. To a much lesser extent, and without the anger, Joe Clark was just as obsessed with strategy when he was young, then developed into a more thoughtful politician. But Clark never made politics personal the way Poilievre does.”

Why do you think Poilievre distrusts the Hill media so much? “I distrust the Hill media. They’re the last people to realize they must get their act together very quickly. They need to stop seeing themselves as political players, spend some time outside their bubble, and end their craving for access, which never produces great journalism.

“At the same time, they made Poilievre. He’s been a favourite dial-a-quote for decades. I find it odd that he so utterly despises journalists who fawningly covered his campaign against WE Charity in 2020-2021, and turned a fairly uncritical and a very lazy eye to his pro-convoy work in 2022. I suppose his disdain is grounded in the right-wing myth of a liberal press. Donald Trump and Stephen Harper believe it, too.”

Why do you distrust the Hill media, especially as a former Hill journalist? “I believe informing the public is not the top priority of many Hill journalists. I see far too much social climbing and status seeking with journalists more concerned about ‘access’ than bravely telling people what’s going on. With some very notable exceptions, press coverage of the Hill is just the repetition of some interest group or politicians’ talking points and analysis by people who have a minimal understanding of law, economics, history, and public administration and no research skills to speak of. Too often, public affairs are covered as sports or social events. I suppose that’s what media managers in this country thinks sells, though it doesn’t seem all that interesting to the vast majority of people.”

What do you think of Poilievre’s treatment of the Hill media? Does it work for him? “If I were advising Poilievre, I’d suggest he give separate substantial interviews on policy to senior journalists from all the country’s major media outlets to try to put to rest the idea that he’s a policy lightweight, if, indeed, he isn’t one. [Liberal Leader Mark] Carney and [NDP Leader Jagmeet] Singh would be smart to do the same thing. All the party leaders seem to me to see all journalists as bad-faith actors, which is understandable, considering some of the recent big media failings.

“Still, I believe the campaign should be covered, and that candidates should have the self-confidence to deal with journalists. The situation has been getting worse over the years, and the public doesn’t seem interested in punishing candidates and government leaders who shun the media. Nor do journalists stick together and push back, so I expect it to work.

“If real media want to survive in Canada, journalism needs to professionalize: real qualifications, professional standards, and a mechanism to enforce those standards in a meaningful way, including the discipline and, if necessary, expulsion of bad actors. So much of the media’s problems are created by journalists themselves, and the door is wide open to propagandists and political actors claiming to be media. Without rebuilding credibility, it’s impossible to get public support.”

What do you think will happen if Poilievre wins the next election? What kind of prime minister would he be? “I believe Poilievre is an honest man. He will keep his promises. And, after making the same ones over and over again, I can’t see how he can get out of them. That means the defunding of the English CBC. It also means the end of support for mainstream print media, which is probably a good thing since most dailies in Canada have minimal readership and do so little coverage.

“He’ll cut all climate-change mitigation efforts, and stop or greatly reduce foreign aid. Each one of those things could, and should, have been major election issues, but our relationship with the United States has dominated the campaign so far. It’s hard to know if he’d have a decent cabinet, since we can’t be sure who’s going to be elected, but it probably wouldn’t matter much. His campaign already shows how much he depends on a small group around him and that he doesn’t listen to anyone else. My biggest concern is that he’ll be weak at the knees around Trump and his enablers. They are, in so many ways, on the same wavelength.”

What if he loses? What do you see unfolding as a result of that both in the party and across the country? “If he wins, he’s fine. If the election is a minority, he goes back on the road with a good chance of winning next time. In the next election, the Liberals would be seeking their fifth mandate. Canadians have given a party a fifth term just once, in 1953. Sir John A. Macdonald and Sir Wilfrid Laurier couldn’t win five elections in a row. Neither could Pierre Trudeau or the Liberals under Jean Chrétien and Paul Martin.

“It gets interesting if Mark Carney were to win a majority. The knives might come out for Poilievre. They certainly will for Jenni Byrne and others on the Conservative campaign team. But I don’t see him going without a nasty fight. He’s actually done a good job on the campaign, so far. If the Liberals win, seats will come from the Bloc Québécois and the NDP, not the Conservatives. That should mean something. As well, Poilievre won the leadership with the support of a large block of people in western Canada and rural-small town Ontario who believe in him and will not turn on him. And there’s no obvious successor. That means the Conservative establishment would have to drag him out, and I don’t believe they have the political muscle to do that.”

Ripper: The Making of Pierre Poilievre, by Mark Bourrie, Biblioasis, 430 pp., $28.95.

The Hill Times

LICENSING

LICENSING PODCAST

PODCAST ALERTS

ALERTS