Parties have ‘free rein’ with voter data, finds report, but veteran party ops say that’s vital for democratic engagement

Canada’s federal political parties are in an “arms race” when collecting and using voter data, say advocates calling for stricter privacy laws, but several veteran political operatives say parties need these practices to fulfill their unique democratic role.

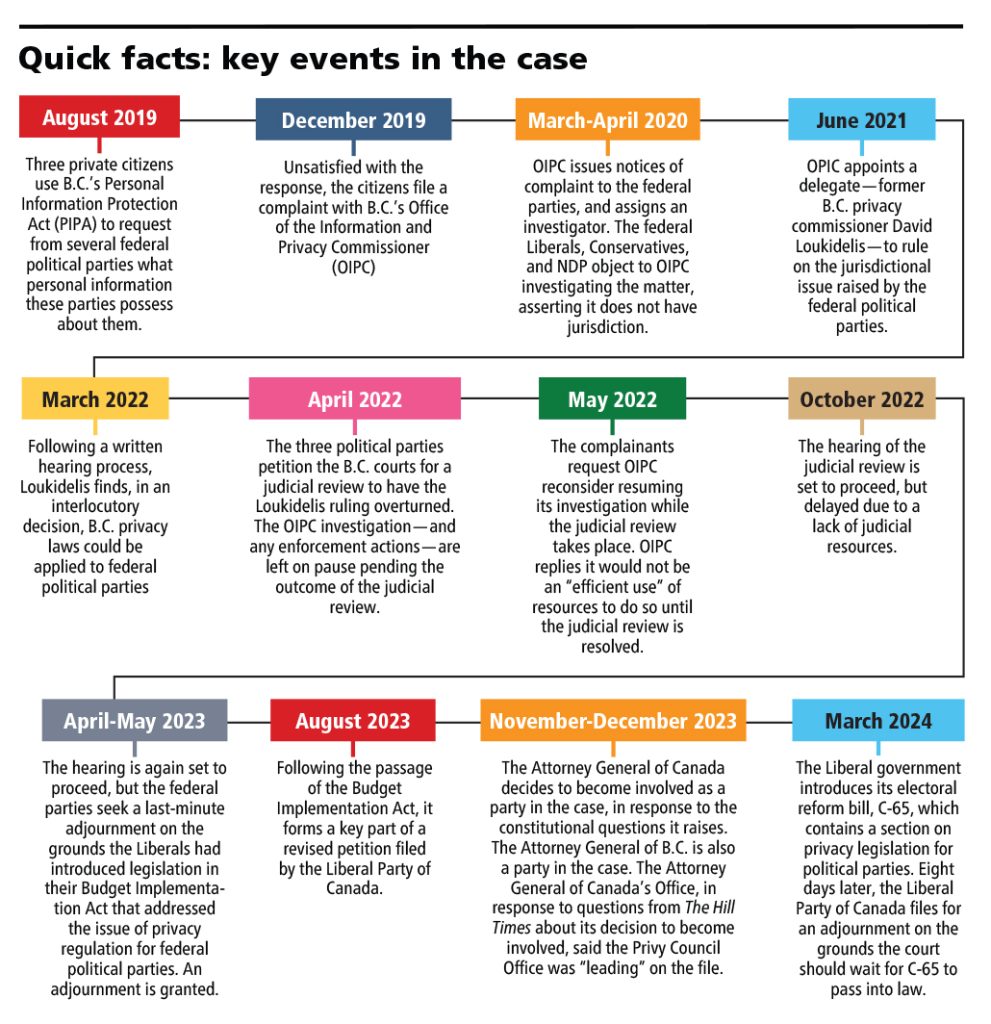

This issue is at the heart of a judicial review beginning in a British Columbia courtroom on April 22. At stake is whether federal parties are subject to B.C.’s privacy laws, which are far more stringent than the current federal rules governing their behaviour. The case was set in motion in 2019 when three private citizens sought to use B.C.’s privacy laws to inquire what information the federal political parties possess about them—a request that cannot be made under federal law. The federal Liberals, Conservatives, and New Democrats objected, saying the B.C. privacy commissioner did not have jurisdiction to investigate these complaints, and that federal political parties were to be solely regulated by the Canadian Parliament.

Those jurisdictional and constitutional matters are among the legal issues being hashed out in the B.C. court. The trial will also examine if the request for judicial review was premature.

However, those calling for stricter privacy rules say their primary goal is not to make federal parties subject to provincial laws. They would welcome a federal statute to create stricter rules about the use of voters’ data. They say Bill C-65, the government’s electoral reform bill currently before Parliament, does not meet that standard.

“This whole complex and expensive case would go away if the federal political parties agreed to apply the same standards to their operations that they have been happy to impose on government agencies and private businesses over the years,” digital privacy expert Colin Bennett previously told The Hill Times.

However, several veteran campaigners say political parties are not the same as other entities.

Scott Lamb, a former Conservative Party president who is also a B.C.-based privacy lawyer, said that parties are “players in the democratic process,” and that means they must be treated differently by privacy law than businesses, governments, and not-for-profits.

“The essence of a political party is public engagement,” said Lamb. “So barriers to engagement are not actually a good thing.”

Fred DeLorey, who served as national campaign manager for the Conservatives in 2021 and held a variety of senior roles in the party, said “at the end of the day, political parties need to be able to communicate to Canadians.”

“Soliciting through email and that sort of communication for corporations is heavily regulated for good reason—because it’s spam,” said DeLorey, who is now a partner at Northstar Public Affairs. “But this is basically the democratic right of political parties to be able to communicate with people, and you can’t hinder that. So privacy legislation needs to be very cautious.”

Dan Arnold, a Liberal pollster who served as director of research on the party’s last three federal campaigns and has worked in the Prime Minister’s Office, also said parties would have reason to be concerned about tighter privacy laws. It’s their job to “identify voters and get them to turnout on election day.”

“If there is anything that makes it more difficult for them to do that, that’s why I think we see some opposition there,” said Arnold, who is now chief strategy officer at Pollara.

Parties have ‘free rein’ with data, finds OpenMedia study

However, a soon-to-be-released report from OpenMedia, an advocacy organization that looks at digital issues in Canada, says the way the parties use data could have adverse effects on the democratic process.

Executive Director Matt Hatfield said the parties are doing what the federal laws allow, which is “writing their own rules” for their privacy policies.

That leaves the door open to collecting any sort of data they choose. Each party’s privacy policy lists illustrative examples of data they collect, but that’s only “the portion they’re telling you,” said Hatfield.

“They give themselves free rein to collect absolutely anything they want,” he said. “They’re not actually restricting themselves.”

An advance copy of the report provided to The Hill Times found the current privacy laws for federal parties allow them to violate at least six of the 10 privacy principals in PIPEDA—the federal law that governs the private sector. This includes principles such as requiring consent to collect information, limiting collection and use to what is strictly necessary, and providing citizens with a way to inquire what information the parties possess about them and correct it if it is inaccurate.

The B.C. law follows the same principles as PIPEDA, meaning that federal parties could become subject to these rules, pending the outcome of the judicial review.

One of Hatfield’s key concerns is tied to door-to-door canvassing where parties may record not only the information a voter tells them, but also note any details about what they observe on the doorstep.

“They can write anything down that they want on their clipboards,” he said. “They can write, ‘Hey, he’s got a nice car, probably in the upper income brackets,’ and make that part of how you’re targeted by whatever advertising or engagement political parties choose to do.”

Hatfield said there are also concerns about how that data, once collected, is used to microtarget voters, and how this impacts the democratic process.

“I really worry about a world in which people are coming to canvass at your door not with a sort of genuine open presentation of what a party’s fundamental policies are, but really with a pre-script written by AI [artificial intelligence] based off this data they’ve collected,” said Hatfield. “It’s really, I think, distorting our abilities to have a public conversation.”

He said this can drive polarization between regions or demographics.

“One of the areas the Liberals have gone wrong in their time in office has been—they were amongst the first to really champion this kind of microtargeting of voters—and I think at a certain point, it’s interfered with their ability to speak to Canadians at large,” said Hatfield.

“They are so focused on policies that speak to very specific demographics,” he said, “they’ve lost the plot of telling Canadians what the country as a whole needs to be doing. And I worry we’re just going to see more and more of that.”

Laws that hinder ‘get out the vote‘ efforts are ‘anti-democratic,’ says DeLorey

Arnold said that parties do collect data and use it for predictive modeling and targeting, but said this has a place in the democratic process.

“Essentially, what a predictive model is doing is it’s collecting all of the data that the parties know about an individual voter—and a lot of that can come just from what door-knockers have found out about these voters over the last couple of elections when they’re going door to door … so you can kind of predict some things based on that,” said Arnold.

“You can predict based on ethnicity, based on the name, and so basically you’re taking all the data that you know about people, and their neighbours, and any polling that you have, and putting it into a giant algorithm that is basically telling you, you know, this person is 60 per cent likely to turnout, and they are 38 per cent likely to vote Liberal if they turnout,” he added. “Even if you haven’t knocked on their door, based on the model, you can kind of tell who those people are.”

He said this could also be used to allocate resources, such as targeted mail drops, advertising, or even sending a volunteer or candidate to visit voters that the model identifies as persuadable.

Arnold disagreed that the parties’ use of models to make campaigning decisions would limit voter engagement.

He said if voters want to find out more about political parties, there are lots of opportunities such as attending local debates, looking at websites and social media, or calling a campaign office and asking for further details.

Even if tighter rules were to limit the use of data, Arnold said there would always be some targeting “based on geography or just gut feelings.”

“Justin Trudeau is not going to drop into Medicine Hat in the next federal election campaign and go meet voters there—because he’s picking ridings he thinks he can win,” said Arnold. “Or a Conservative door-knocker is going to see a hybrid in the driveway with ‘I Love the CBC’ bumper stickers, and is just going to skip the door.”

DeLorey also made the case that data plays a positive role.

“At the end of the day, politics comes down to one thing: whoever can get their voters to vote,” said DeLorey. “This goes back from the beginning of democracy. The way you win is you ID your vote, and you bring them out to the polls. And anything that hinders that is problematic, and in a sense, anti-democratic.”

Asked about some of the privacy principles in question—such as consent or limiting data collection and use—he said this could make it harder for parties to understand their voters.

“There’s tremendous risk potentially here that it will become too cumbersome for political parties to collect data,” said DeLorey. “If that happens, then they may lose a sense of what their supporters believe in.”

Lamb said imposing principles like obtaining consent and limiting collection to what’s strictly necessary would unreasonably impede the work of campaigns, particularly because of the large role played by volunteers.

He said the Liberals and Conservatives operate with a core staff of about 60 to 80 people, but take on thousands of volunteers at election time. He said an organization of this nature cannot comply with procedures to obtain consent the same way a private business can, and that an interaction on a doorstep should be considered implied consent to collect data.

He also pushed back against the suggestion that targeting voters to communicate with them about a particular issue was bad for democracy.

“You can look at that in a negative way. Or you can look at that in a positive way,” he said. “We’re engaging them on the issue they care about. That’s what we really want to do. … That’s actually how people do vote.”

However, Hatfield said the increasingly sophisticated tools used by the parties were “playing with fire,” and called on them to step back.

“We need to de-escalate the arms race,” he said. “Not in a way that benefits one [party] over the other. But if everyone agrees … at least ramp this down some from a race that I think has gotten increasingly frenetic and that I think AI is going to really magnify over the next three to five years.”

icampbell@hilltimes.com

The Hill Times

LICENSING

LICENSING PODCAST

PODCAST ALERTS

ALERTS