New housing minister’s ‘first-week jitters’ on home values needs clarification, says policy expert Mike Moffatt

Prime Minister Mark Carney can’t afford to allow first-week cabinet jitters to dilute his government’s messaging on the housing crisis, says economist and progressive policy expert Mike Moffatt. But to truly address affordability, the government will have to admit that homeowners won’t be able to keep all the value.

“The prime minister is willing to acknowledge that housing prices do need to fall, but the housing minister would not,” said Moffatt, an associate professor of economics and public policy at Western University’s Ivey Business School. “Overall, Canada now seems to have two parallel housing policies: one from the prime minister, and one from the housing minister.

Writing for The Hub in the immediate aftermath of the cabinet shuffle on May 13, Moffatt, an executive with the Smart Prosperity Institute and host of the Missing Middle podcast, described the selection of former Vancouver mayor Gregor Robertson (Vancouver Fraserview–South Burnaby. B.C.) as Carney’s (Nepean, Ont.) newest housing and infrastructure minister as a “high-risk, high-reward” decision.

However, in his first week, Robertson produced “far more risk than reward,” Moffatt told The Hill Times in a May 15 interview.

Less than 24 hours after being named to the role, Robertson had already created the impression that he and Carney “are not on the same page” regarding how to solve Canada’s housing affordability crisis, Moffatt said.

During a post-shuffle press conference at Rideau Hall on May 13, Carney was asked whether his decision to select Robertson as housing minister signals that he does not believe housing prices need to fall, given the nearly 200-per-cent increase in housing prices during Robertson’s time as the mayor of Vancouver.

“You would be very hard pressed to come to that conclusion,” Carney responded, pointing to his past statements and his government’s priorities.

“We have a strong view on housing, a very clear policy … developed with a number of members of the team, including with Mr. Robertson, and I’m thrilled that he’s in the new role,” Carney told reporters, noting that Robertson has the “type of experience that we need to tackle some aspects of this problem,” like reducing municipal costs and regulations.

“Ultimately,” Carney continued, the housing crisis will be solved with an “aggressive” objective to double the construction of new homes in Canada.

However, as he entered his first official cabinet meeting the next morning, Robertson gave journalists and Canadians the impression he had reached a slightly different conclusion.

“No,” Robertson told reporters when asked if he believes “housing prices need to go down.”

“I think we need to deliver more supply [and] make sure the market is stable,” Robertson continued. “It’s a huge part of our economy. We need to be delivering more affordable housing.”

Later in the evening, Robertson attempted damage control. Just after 10 p.m., Robertson took to the social media platform X, and attempted to reframe the question he thought he was answering as whether he believed in “reducing the price of a family’s current home, which for most Canadians, is their most valuable asset.”

When questioned about how he plans to make homes more affordable without reducing the price of a pre-existing family home, Robertson said the solution would be to “build more homes at scale.”

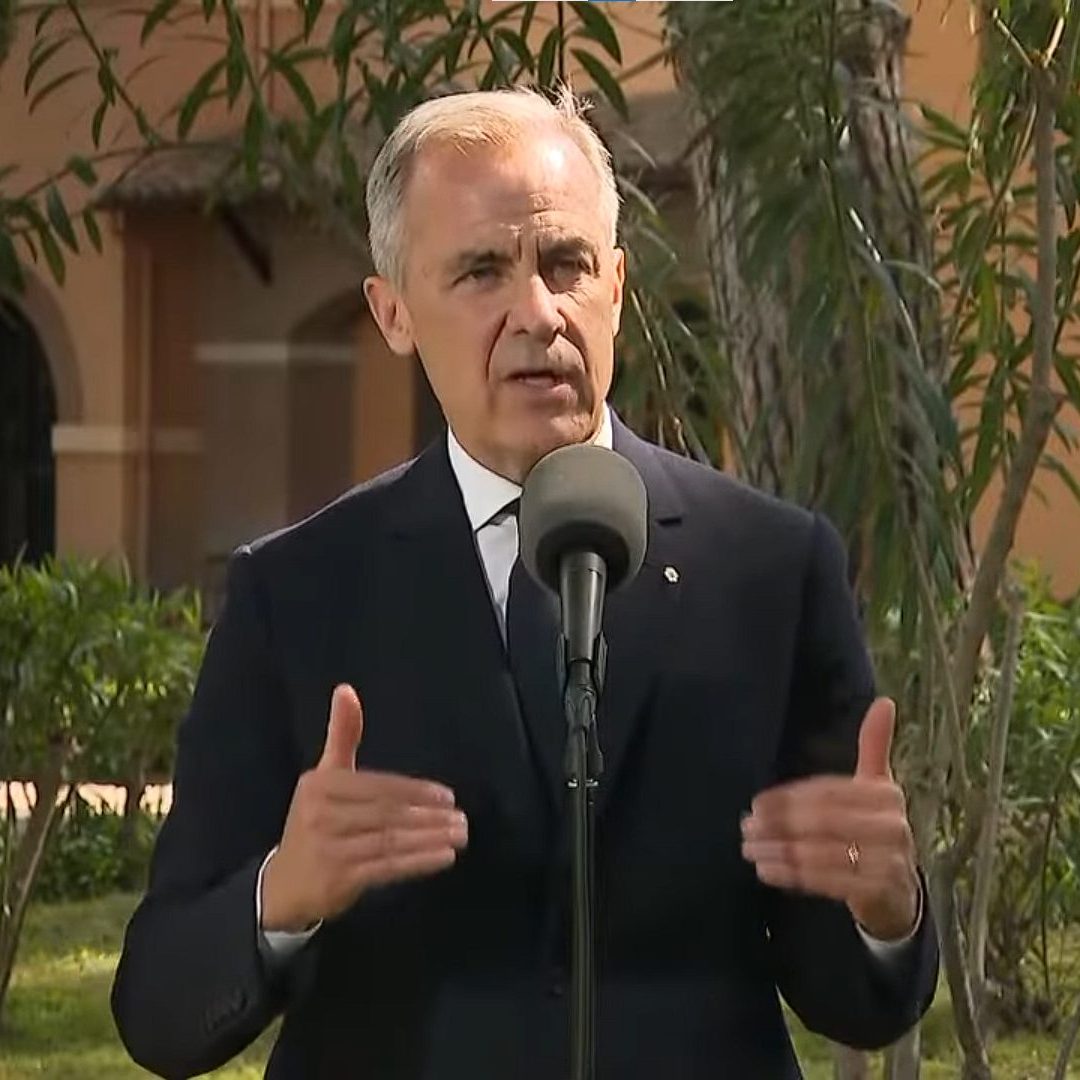

During a May 18 press conference in Rome, Italy, where he had travelled to attend the inaugural mass of Pope Leo XIV at the Vatican, Carney said housing affordability is not a simple “yes or no” question.

“It’d be lovely if we could always get very simple, yes, no … up, down [answers] to the economy, but we’re talking about time horizons,” Carney told reporters when challenged to give his answer on the issue.

“The core issue for younger Canadians—for all Canadians—is that the level of house prices goes down relative to their incomes, so the affordability goes up,” he continued, pointing to measures his government would take to cut costs on new home construction, including cutting the GST on new homes under $1-million, halving development charges, and scaling up a more efficient domestic construction industry.

“All of those factors are going to help to improve affordability,” Carney said. “The exact level of house prices, of course, is going to be a function of a variety of factors, including where incomes grow, but the key is that we’re building new homes, and the purchase of new homes becomes less expensive. Absolutely, without question.”

Moffatt said Robertson’s answers on what to do about housing prices have been confusing and contradictory since becoming minister. He noted that while the original answer began with a “no,” the rest of Robertson’s reply contained numerous supply measures that would cause overall prices to go down.

“Obviously, he’s a rookie who had been in that role less than 24 hours, so I think the charitable view would be that this is kind of first-day jitters,” Moffatt said, noting that the short timeframe from his swearing in would have given little time to memorize talking points.

“I would like to see him clarify because until then there certainly does seem to be a pretty big misalignment between the Robertson’s talking points and the prime minister’s,” Moffatt said.

Robertson’s office told The Hill Times that “overall housing prices” would need to come down across the country to solve the housing crisis.

“It’s not about reducing the value of an individual home—it’s about ensuring everyone in this country has good housing options they can afford,” wrote press secretary Sofia Ouslis. “We will get more homes built by cutting taxes and fees on the construction of new housing, removing municipal roadblocks … and by getting the federal government back into the business of building affordable homes at a scale not seen since after the Second World War.”

However, Moffatt also noted that Robertson had further muddied the waters on his government’s “very clear” platform promises to lower housing costs, particularly development charges.

During a May 13 interview with the CBC’s David Cochrane on Power and Politics, Robertson was asked about increasing development charges as Vancouver mayor. He defended these charges as “cost recovery” for municipalities to invest in infrastructure, and a way for those cities to “rebalance” their budgets.

“When market housing is selling at those rates, we may as well take some of that back into the public purse,” Robertson said. “Developers are making money … just got to make sure that the [government] isn’t giving everything away.”

Moffatt said he understands the tightrope Liberals are attempting to walk: balancing owners whose home values are their retirement plans, and those hoping to buy their first home. However, he said it would be better for everyone if the government were more explicit about those competing interests rather than pretending the conflict doesn’t exist.

“I understand the concerns of existing homeowners, but we need the cost of constructing new homes to fall, and that means some existing homes will fall in value, too,” Moffatt explained, noting that even if housing prices just remained flat, it would take up to 50 years for middle-class wages to catch up.

“The more important thing is for the cost of building new homes to go down, but we need to say both,” Moffatt said. “Otherwise, it just looks disingenuous or incoherent at best.”

The Hill Times

LICENSING

LICENSING PODCAST

PODCAST ALERTS

ALERTS