Liberals’ recycled plan to fix ‘badly busted’ defence procurement can take root in Trump era, say experts

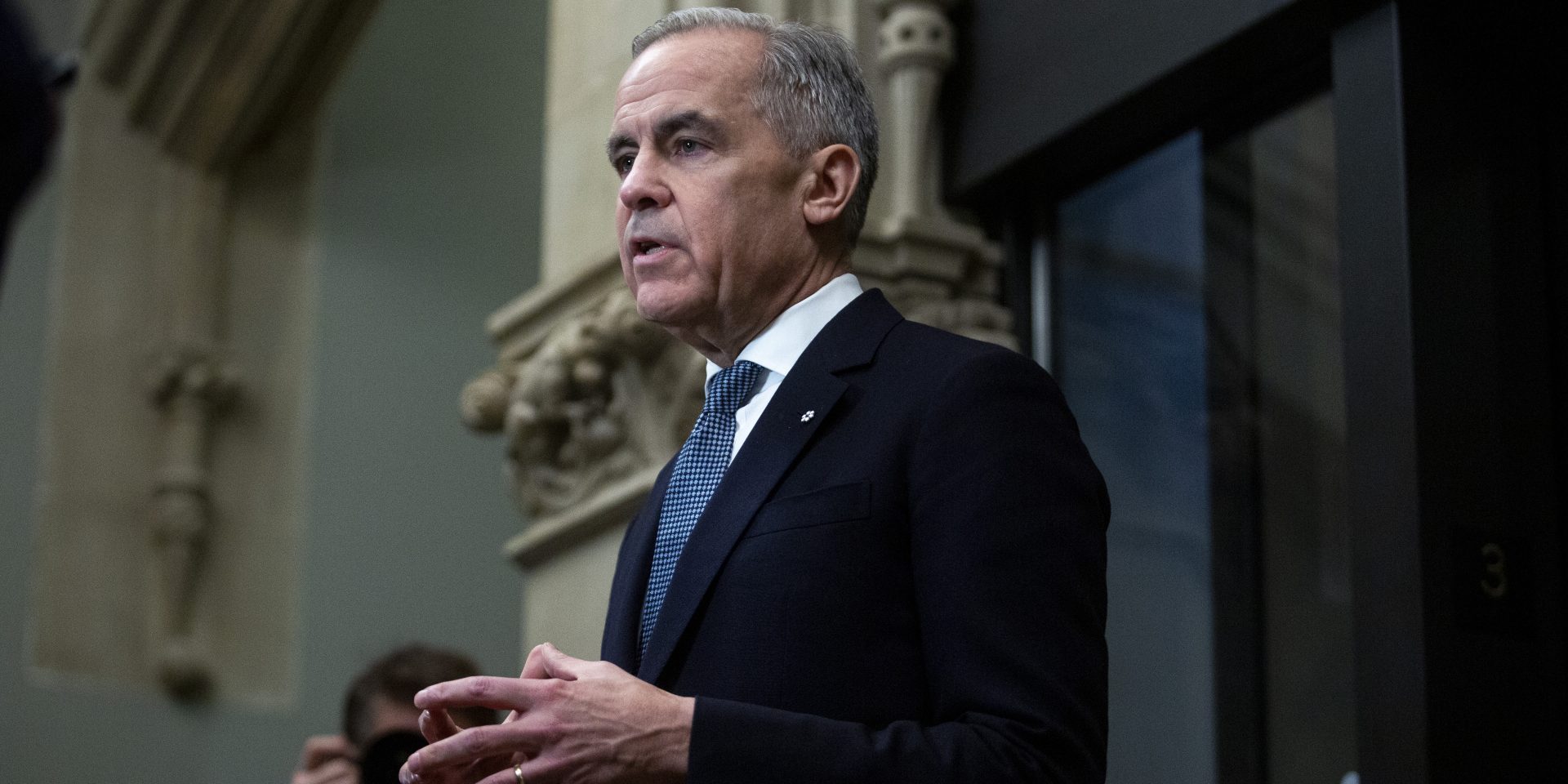

Amid mounting American trade threats and global instability, Prime Minister Mark Carney recycled the Liberal promise of overhauling Canada’s problem-plagued military procurement system through a new centralized agency. That pledge, floated repeatedly over the past two decades, could take root if the next government has “the political imperative” to follow through, but it won’t solve everything, say defence experts.

Carney announced a series of measures on April 14, including establishing a new “Defence Procurement Agency” to centralize expertise within the government, streamline the process for acquiring military equipment, and modernize procurement rules. This builds on the Liberals’ 2019 campaign pledge to create a standalone procurement agency, an idea that’s been floated repeatedly, but never implemented.

Carney’s plan also includes establishing a bureau of research, engineering, and advanced leadership in science to ensure the Canadian Armed Forces and Communications Security Establishment have homegrown solutions in advanced research and technology, as well as support for domestic defence firms looking to expand internationally to grow their sales. He also committed to a “buy Canadian” approach for steel, aluminum, and critical minerals purchases.

All these promises come as part of a broader effort to reinvest in the military and diversify trade in response to tariff and annexation threats from United States President Donald Trump.

The prime minister’s plan is doable, but it hinges on political will, according to former federal Liberal defence minister David Pratt, who is currently the principal of David Pratt & Associates. He argued conditions are more favourable than ever with rising public support, U.S. pressure, and geopolitical urgency.

“The political imperative that exists to move quickly and efficiently with a sustained effort to improve the procurement process and make greater defence investments is stronger today than it has been since the end of the Cold War,” he said.

On whether a new agency would slow things down, Pratt said that if done right, it could even speed things up.

“If it is properly constituted, this new procurement agency will cut a portion of the bureaucracy out of the process, and accelerate the acquisition of new equipment and technologies. The critical factor will be the expertise and experience that the people in this agency bring to the task. There will undoubtedly be mistakes made, but the benefits in the long run will outweigh any teething problems,” Pratt said.

The former minister argued Canada can learn from its allies as well as from its own history when military equipment was acquired more quickly and efficiently. “Military procurement, in some respects, really needs to go back to the future,” he said.

Outgoing Liberal MP John McKay, erstwhile chair of the House Defence Committee, did not deny that Carney’s promise is a recycled one, but told The Hill Times that the combination of Trump-era unpredictability and an increasingly dangerous geopolitical environment has helped defence become a priority in the public’s eyes.

“This is the first time in my living memory where defence and security policy has been a central discussion among the political classes, and even among the Canadian electorate,” he said.

McKay argued that whether through an agency, secretariat, or a procurement czar, there are urgent and critical procurements that need to move quickly.

He said that Carney understands that “if you are going to reduce your security vulnerability, you need to have a very robust defence capability.”

“I think it’s a much larger response than just, ‘Oh well, we’ll put this in the window and call it a platform plank,’” added McKay.

A 2024 report by the House Defence Committee offers a roadmap for fixing this country’s procurement system, and would provide a roadmap to all party leaders including Carney, McKay said. However, he noted many of the report’s recommendations rest on the assumption that the U.S. remains a reliable ally.

“The system is busted. It’s badly busted. It’s risk-averse, and decisions aren’t made in a timely or effective way. And we no longer have the luxury [to continue to operate] in the current system we’re operating under,” McKay said.

Lack of accountability is why there’s ‘chaos’, says Williams

Alan Williams, a former assistant deputy minister of materiel at the Department of National Defence (DND), was also the one of the first people to pitch the idea of centralizing procurement under one accountable authority almost 20 years ago. He said he has championed it ever since while speaking to MPs at standing committees and with party representatives.

“It’s not nuclear science. I worked in PSPC [Public Services and Procurement Canada], and then I worked in DND. It was pretty clear to me there is such inefficiency and such wastage … it made total sense,” Williams said in an interview. “Why does everybody else have one minister accountable, and we don’t?”

The Liberals’ 2019 federal election campaign promised to create a centralized agency named Defence Procurement Canada that would streamline the process for major defence projects. Williams said such an overhaul is as easily doable now as it was back then.

It would save money and time in the long term, and it would hold the government to account, Williams said, but he argued lethargy, political risk aversion, and bureaucratic resistance are key reasons why governments have avoided implementing the change.

“Up until now, there hasn’t been any imperative, and it’s not like the rest of the country cared much about defence,” he said. “It’s not an issue that will generate votes … so why change if you don’t have to? It’s the inertia.”

Williams argued that the core problem with Canada’s current procurement system is the absence of a clear chain of command or final authority when things go wrong—with responsibility spread across PSPC; DND; and Innovation, Science, and Economic Development.

“No matter how you do it, the key is to hold one person accountable at the top and make sure that you have performance measures going. It’s an easy thing to do legislatively,” said Williams.

“This is the only part of our government where the prime minister cannot go to a minister and say you’re accountable for this,” he said. “And if you don’t have somebody accountable… You can’t put performance measures in and it just leads to mediocrity.”

Between the turnover of ministers and deputy ministers, and the errors and overlap and duplication of work, “it just slows everything down to the slowest part of the process. That’s why you get the kind of chaos you have in the system today,” Williams said.

Eugene Lang, former chief of staff to two federal Liberal defence ministers, said it is a “seductive” idea to establish a separate procurement agency, which is why it resurfaces time and time again.

“It’s all fragmented and decentralized, accountabilities are diffused now. Get the accountability consolidated in one place, and it’s going to be more streamlined, more efficient and accountable. So at its highest level, it’s a very seductive idea, until you dig into the complexities of actually executing on it,” he said.

Another reason why this keeps coming up, according to Lang, is that no one has publicly come up with a compelling alternative that would meaningfully reform defence procurement.

Yet, Lang said he is “skeptical” about such an agency being implemented successfully, given “big, complicated machinery-of-government changes rarely live up to their expectations, rarely deliver the desired results.” He argued that sometimes they create entirely new problems.

Lang said the term “agency” could refer to anything from a special operating unit within a department, or a full-blown, arm’s-length organization like a Crown corporation, all of which would have different levels of ministerial accountability and legal autonomy.

Lang said the implementation of Carney’s plan would require changing legislation, creating a new organization, transferring regulatory authorities, and potentially moving thousands of staff across departments.

“The complexity of that is significant. In fact, I can’t think of a more complex machinery-of-government change that’s been contemplated in the last 30 years,” Lang said.

As for Carney’s commitment to prioritize Canadian industry and to grow domestic defence manufacturing, Lang said while it is “long overdue,” it is refreshing to see a Canadian leader “who believes in building up the domestic defence industry, generally and, in particular, in these times of peril that we’re in right now.”

Christyn Cianfarani, president and CEO of the Canadian Association of Defence and Security Industries, said while it’s “tempting,” it’s not clear yet how Carney’s recycled pledge could be actualized, and added that a centralized agency “would not, by itself, fix the problems in the procurement system.”

“The changes needed to the current machinery of government would be huge, and the growing pains during that transition could slow down procurement at a time when Canada needs to speed it up,” she said.

Richard Shimooka, a defence procurement expert and senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, expressed skepticism about Carney’s recent pledges, suggesting they may be more rhetorical than substantive.

Shimooka said that the creation of a new agency could be “effective” in streamlining the process, but said, “if it’s just moving boxes around on an organizational chart, it’s not worth doing.”

“It’s nice to have these structures, and we can rearrange this, but if the money isn’t coming through, then what’s the point?” Shimooka said.

Cianfarani said Carney is “saying a lot of the right things” in terms of favouring Canadian firms, building up our defence industrial base, supporting defence exports. “Those are all strategies that the defence industry has called for, and they are certainly doable,” she said.

But she added, that “the devil will be in the details. Most importantly, the money will need to align with the ambition and reflect the urgency.”

As for whether or not the Canada’s defence sector has the capacity to meet the demand that could stem from Carney’s “buy Canadian” approach, Cianfarani said, the industry has “plenty to offer, but it needs clear marching orders and an overarching strategy.”

ikoca@hilltimes.com

The Hill Times

LICENSING

LICENSING PODCAST

PODCAST ALERTS

ALERTS