Define ‘Canadian’: questions loom over Carney’s ‘protectionist’ procurement policy push

Prime Minister Mark Carney’s new “Buy Canadian” policy promises to steer billions of federal dollars toward domestic suppliers in response to the tariff war with the United States, but procurement experts say departments and industry need clearer rules for interpreting the “protectionist” directive.

Carney (Nepean, Ont.) unveiled the new policy on Sept. 5 with the stated aim to ensure Ottawa buys from domestic suppliers. While full details of how the policy will be implemented remain unclear, a backgrounder from the government outlined that it will streamline rules and support business so they can access federal procurement, including Crown corporations, provinces, territories, and municipalities.

By November, the government is planning to introduce new measures to make sure Canadian suppliers and their products are prioritized in all federal spending. The new policy is expected bring an additional $70-billion more in spending.

Easy political sell, hard policy shift

Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC) did not respond to The Hill Times’ questions about whether the Prime Minister’s Office has directed departments or provinces on how the policy would be implemented.

Some, like Ian Lee, an associate professor at Carleton University’s Sprott School of Business, argue that Carney’s “Buy Canadian” push is a populist move tapping into nationalist sentiment amid tariff wars, but it’s “counterproductive.”

“It’s the equivalent of shooting yourself in the foot. But it’s popular politically,” Lee said.

Lee argued that what he called a “protectionist” move could hurt the nation in the long term by circumventing competition and inflating costs, leaving Canada vulnerable in a global market dominated by production giants like the U.S., China, and Europe.

“Protectionism… does not protect us. What it does is it immunizes firms from outside competition, and makes them weaker,” Lee said.

“The idea that we’ll become a world-class competitor … across many technologies, going it alone … it is preposterous. … It’s delusional. We’re not big enough.”

“It is nothing about political will. We don’t have the scale.”

This policy would initially cover Canadian steel and softwood lumber, and would be flexible to allow the feds to include more domestic materials in the future, according to the government. The government will also launch a new Policy on Prioritizing Canadian Materials in Federal Procurement that would require domestic and foreign suppliers contracting with Ottawa to source key materials from Canadian firms in defence and construction procurements exceeding a certain threshold.

Many, like former Privy Council clerk Michael Wernick, question the government’s definition of Canadian content, and how it will fit into the general policy objectives for procurement.

“Will it bump and override other policies, or is it additive to a checklist?” he asked.

“Does the American-owned GM plant in London [Ontario] that makes heavy vehicles count as Canadian? Is Lockheed Martin still eligible for the fighter contract if it has a subsidiary in Canada? Both steel mills in Hamilton [Ontario] are foreign owned. Do they count?”

Wernick argued the implementation challenge is going to fall largely on PSPC as the feds’ central purchaser, which he said prompts questions such as whether the government will invest in training and digital tools for procurement teams.

He also described the policy as protectionist, but said the argument in favour of this approach has always been that it builds capacity and creates jobs to protect sovereignty—and it’s worth taking the risk.

“We won’t really know the outcome for several years,” he said.

Jennifer Robson, associate professor at Carleton University, said it’s hard to predict how the policy will be rolled out, but the implementation will matter. Departments will have to figure out administratively how to interpret the new policy directive.

“There is an administrative burden here,” she said.

Robson explained that once the policy kicks in, departments will have to monitor and enforce it, which is going to require people focused on the goals, and new terms and conditions added to existing rules that govern the transfer of money, or new funding deals.

Robson echoed that defining what is Canadian will be “really hard,” expanding on the issue in a Sept. 8 Substack post.

“The politics of this may be tricky, even if the economics of it should be straightforward. But I seem to recall a prime minister who promised to govern in econometrics,” Robson wrote.

According to Statistics Canada, in 2023, foreign and Canadian multinational enterprises in this country employed 5.1 million people and traded $1.2-trillion worth of goods internationally.

Departments, industry need clear, early guidance, say experts

Mary Anne Carter, principal with Earnscliffe Strategies with expertise in global trade and Canada-U.S. relations, said Crown corporations and provinces could adopt the policy, but it will come with challenges.

“Without clear federal guidance and shared tools, there’s a real risk of higher costs and slower project delivery,” she said, adding that those challenges can be compounded by regional disparities, “as some provinces have stronger supplier bases than others, raising questions of fairness and consistency across the country.”

Premiers of Ontario, Quebec, and British Columbia have previously talked about limiting American firms from provincial procurement during ongoing tariff tensions, but those statements have not yet translated into concrete action.

Another risk would be pushback from trade partners, particularly the U.S., and less competition if domestic rules are too rigid, according to Carter.

“To balance those risks, Canada will likely need to lean more heavily on European partnerships to diversify supply chains and reinforce access to critical inputs,” Carter said, adding that even friendly allies may view the measures as “protectionist,” and push back.

Challenge of defining ‘Canadian’ content

According to Carter, who previously oversaw federal procurement files at the Canadian Chamber of Commerce, tracing Canadian origin in globally mixed supply chains will be “difficult.” It will likely be defined through a blend of percentage thresholds for domestic value and sector-specific criteria, she said, noting that businesses are waiting for clarity on this.

“Many sectors, including EV batteries, defence, and infrastructure rely on globally integrated supply chains, making it difficult to determine what truly qualifies as ‘Canadian content’ whether in materials, labour, or intellectual property without significant diligence,” she explained.

“Procurement officers will likely rely on supplier declarations, domestic value thresholds, and some form of auditing, though that will add layers of complexity.”

Goran Samuel Pesic, president of Samuel Associates who specializes in federal procurement, said Canada can meet a significant share of the government’s demand in areas such as shipbuilding, advanced materials, communications, and cyber, but not without targeted scaling.

“Gaps remain in high-volume munitions, advanced micro-electronics, and energetics. With predictable multi-year demand signals, investment in skilled trades, and allied co-production agreements, Canadian firms could deliver far more domestically,” he said.

Under the new policy, Ottawa committed to formalizing and extending the new policy to include infrastructure spending, grants, contributions, loans, and other federal funding streams. Provinces, territories, and municipalities will be provided with a roadmap they can adopt. A new procurement program will also be set up to create specific streams for small and medium businesses.

New content requirements will be used when the government does not have a choice but to buy from foreign suppliers. And by spring 2026, Ottawa plans to fully implement the new “reciprocal procurement” policy to ensure non-defence procurements are limited to Canadian goods and services.

According to Pesic, by November, departments will need to finalize a government-wide definition of Canadian content, introduce standard contract clauses and attestation rules, launch supplier readiness calls to map domestic capacity, and accelerate security clearances and funding for tooling.

Pesic also noted that a pilot ‘Buy Canadian’ policy should be tested for procurement, and the Industrial and Technological Benefits regime should be reformed to give clearer incentives, reduce red tape, and reward domestic production.

Carter argued that, by that date, departments would also need to build out supplier lists, and train procurement staff, while also signalling any changes to industry early on.

‘There is a price for Canada’s sovereignty’: Khan

Sahir Khan, a former assistant parliamentary budget officer, said the announcement signals an “important shift in policy that will have a significant impact, both on Canada’s economy and its sovereignty.”

“The policy imperatives will drive fiscal pressures, but are necessary, given the geopolitical context, and economic growth can offset some of this cost,” he said.

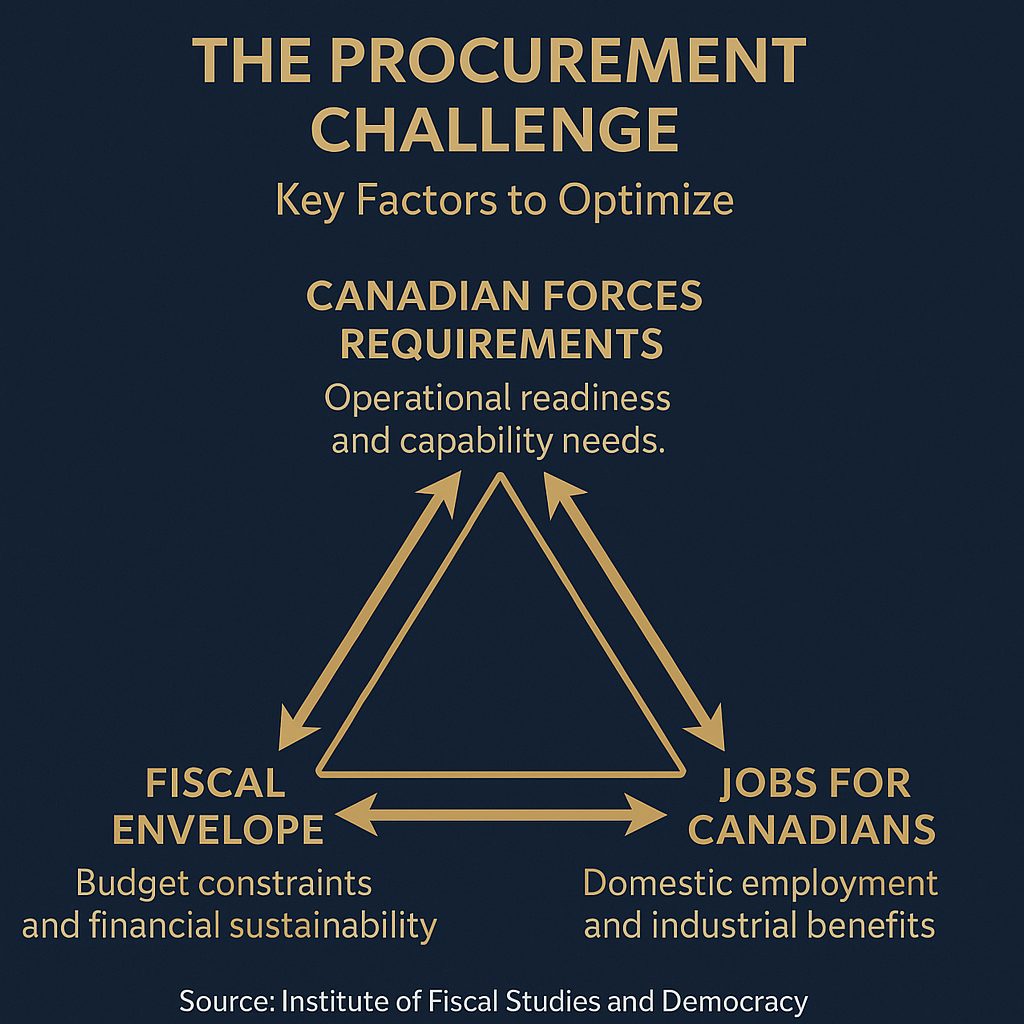

Khan argued the government’s new strategy can ensure Canada’s independence in its infrastructure and supply chains in key sectors of the economy and support Canadian Forces to discharge their mandate more fully.

“This dual use element will have to be a feature of major capital investments to ensure longer-term fiscal and political viability,” he said.

Khan, now an expert in government finances at the Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy, noted that additional fiscal pressure will put upward pressure on the deficit while also driving reallocation of federal spending from lower to higher priority areas.

“But parliamentarians and Canadians will have to accept that there is a price for Canada’s sovereignty. We will start paying this critical national obligation in the October budget.”

The Hill Times

LICENSING

LICENSING PODCAST

PODCAST ALERTS

ALERTS