B.C. voter data complainant calls out microtargeting, as parties mum on next steps after court loss

A private citizen behind a complaint that has led to tighter privacy rules for political parties is calling a recent court ruling a “vindication,” while a former Conservative Party president says the decision leaves the country’s rules for political parties “balkanized,” and should be appealed.

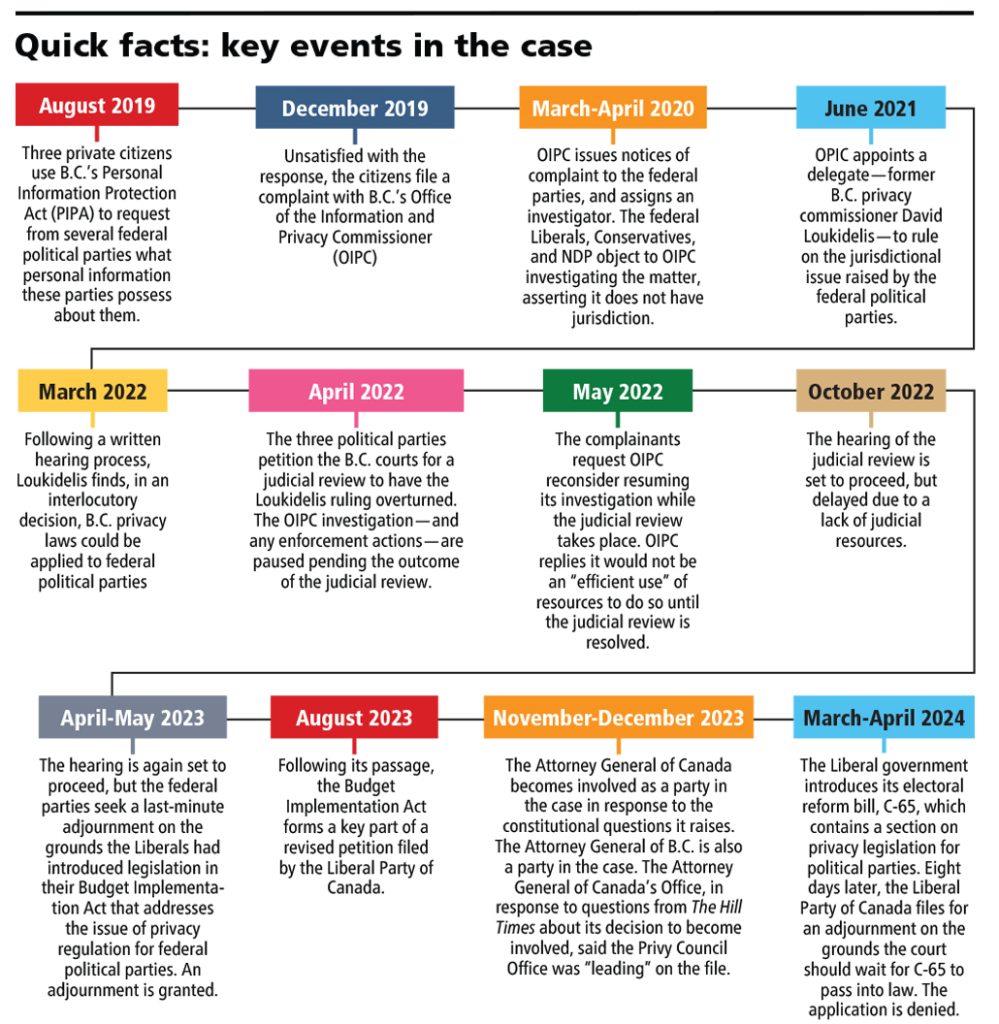

Andrew Clement, a computer scientist and professor at the University of Toronto’s Faculty of Information, was one of three private citizens who submitted a request to several federal political parties in 2019 asking for any personal information the parties possessed about him. That request set in motion a years-long battle with privacy commissioners and in court. On May 15, a British Coulmbia judge ruled that federal political parties are subject to that province’s privacy laws.

“It was really a very clear sort of vindication,” Clement told The Hill Times. “The judge really got the message, and was clear and powerful in his judgment wording.”

Clement and the two other private citizens—who have chosen to remain anonymous—are all British Columbia residents, and used that province’s privacy laws to make the request.

Federal privacy legislation does not cover political parties, while British Columbia has some of the strictest provincial privacy laws in Canada. Provincial political parties operating in British Columbia are subject to its privacy laws, and the three private citizens asserted federal parties also fell under its jurisdiction. The federal Liberals, Conservatives, and NDP objected.

In a May 15 ruling, Justice Gordon Weatherill waded through a series of complex constitutional arguments about the division of powers under federalism, and whether applying British Columbia privacy laws would frustrate Ottawa’s role in regulating federal elections. He ruled that it wouldn’t.

That means federal political parties are now subject to British Columbia’s privacy laws, and a stalled investigation into how the parties collect and use data can resume—unless the parties seek a stay of the ruling pending appeal. If the investigation proceeds, it could shed light on what sort of data the federal parties possess about Canadians, and affect how the parties carry out many activities such as fundraising, canvassing, and getting out the vote.

‘A long pre-occupation’: Clement

A computer scientist, Clement said he has had “a long preoccupation” with “the issues of surveillance and privacy,” which motivated his desire to challenge the federal parties.

“I’ve just been interested in how computerization has been used to basically grab people’s information in all kinds of ways and then process it—whoever’s doing it—to their advantage,” he said.

One of the central concerns privacy advocates have raised is that political parties are using data to create profiles of voters, which is used for microtargeting. They’re concerned about the impact this may have on the democratic process.

Clement said these practices can lead to “fragmented exchanges” where “contradictory messages can be given.” He said having a profile that might tell the party how a voter thinks about a particular issue “exposes you to a manipulative process, rather than a public deliberative process.”

He said that he saw filing the complaint as an opportunity to promote greater accountability for how data is used.

“It just doesn’t make any real sense from a governance point of view that a set of organizations that collect some of the most sensitive personal information are not governed effectively by any privacy regime,” he said.

Clement pointed to the Cambridge Analytica scandal—in which the personal data of Facebook users was collected without their consent and used to craft political advertising—as an example of large-scale misuse of personal information.

He also noted a 2019 report from British Columbia’s Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner (OIPC) that looked into how that province’s provincial political parties were collecting and using voter data. The report found that parties were keeping large amounts of data about voters, including sex, ethnicity, age, languages spoken, religion, income, education, and professional status.

That’s why when the federal parties sent Clement a response to his initial inquiry in 2019, their answer didn’t sit right with him. Clement said the parties claimed to have only some basic information on him, such as his voter registration information including some details related to when he used to live in Toronto. They also provided records of some past donations he had made.

“This didn’t sit with what we knew about the way in which political parties are trying to extract as much actionable information as they can about voters,” he said.

‘Leaves the country a bit balkanized‘: Lamb

Scott Lamb, a former Conservative Party president and British Columbia-based privacy lawyer, said the ruling should be appealed.

“It, unfortunately, leaves the country a bit balkanized, said Lamb. “We don’t have an overarching approach to how political parties—who are very important entities in our democracy—are governed across the country.”

Regardless of the debate on regulating political parties’ use of data, Lamb said he is concerned the ruling could lead to a patchwork of different provincial rules for how federal elections are regulated. He expects those constitutional issues could be central in an appeal.

Lamb also disagreed with tighter privacy rules for federal parties on the grounds that most of the campaigning is carried out by thousands of volunteers going door to door. He said that makes compliance with increased regulation difficult.

None of the political parties have yet stated if they will launch an appeal.

The Attorney General of Canada was also a party in the case, and argued against the application of British Columbia’s laws. Despite that involvement, Attorney General Arif Virani’s (Parkdale-High Park, Ont.) office has consistently sidestepped comment on the matter, pointing media questions to the Privy Council Office—which speaks for Dominic LeBlanc (Beauséjour, N.B.) in his role as democratic institutions minister.

PCO did not offer a reaction to the ruling, or say whether the government would appeal.

“The Government of Canada will further analyze the court’s decision over the coming weeks,” said Pierre-Alain Bujold, a media relations manager at PCO in a statement.

Asked about whether the Liberals would consider new legislation or changes to Bill C-65—the electoral reform bill—in order to create a more robust federal privacy regime that might overtake the need for the application of provincial privacy laws, Bujold indicated Ottawa plans to proceed on the current legislative path.

“Work on Bill C-65 has been ongoing for quite some time. The changes proposed in Bill C-65 are not in response to this litigation—they are a continuation of the Government of Canada’s ongoing enhancement of privacy provisions, which were strengthened for the first time in 2018,” said Bujold. “We look forward to continuing with the process towards royal assent.”

Immediate implications

With an appeal possible, the immediate implications of the ruling for federal political parties remain somewhat unclear.

According to the ruling, the parties are now subject to British Columbia’s Personal Information Protection Act which is based on a set of 10 principles. These include obtaining consent, limiting data collection to what is strictly necessary, and making disclosures to residents who request to know what personal information an organization possesses about them. However, PIPA also makes certain exceptions to these principles, such as allowing non-consensual collection and use of personal information when it is authorized by other laws—such as the Canada Elections Act. Until OIPC’s investigation resumes, it is unclear if the parties are in compliance with the act, or what changes they may need to make to their operating practices.

OIPC told The Hill Times it is consulting with its legal team to determine if and when that investigation would resume.

A spokesperson for OIPC could not comment on a specific investigation, but offered some insight into how the process generally works. He said it would involve gathering evidence from both parties, considering whether the organization was acting in compliance with the applicable privacy law, and issuing findings.

“If a public body or organization is found to have been offside of the legislation,” said the spokesperson, “they will be subject to a legally binding order to take action to comply with the law.”

Lamb said an order would usually relate to one of the principals in the act. For example, it could require a party to shift from relying on implied consent and start obtaining explicit consent from voters on their data—which he said would create undue burden given the voluntary nature of political canvassing.

A final report from an investigation could also shed light on what type of data parties possess on voters.

Editor’s note: This story was updated on May 28 to provide additional context about how the application of B.C.’s privacy laws could affect the operations of political parties.

icampbell@hilltimes.com

The Hill Times

LICENSING

LICENSING PODCAST

PODCAST ALERTS

ALERTS