‘ArriveCan is different than other scandals,’ say experts, warning improprieties ‘erode public confidence’

In the high-stakes world of government spending and procurement where billions of taxpayer dollars are in play, Canada has faced numerous scandals over the decades—some revealing vulnerabilities in government processes, and others sparking fallout that felled political leaders.

The recent controversy surrounding the ArriveCan application—with its inflated costs and allegations of misconduct—brings this issue back into the spotlight.

As a dozen independent investigations—including one led by the RCMP—work to uncover the details of the ArriveCan scandal, experts and politicos weigh in on how it fits into a broader pattern of past controversies.

Is ArriveCan as big of a scandal as AdScam?

Conservative MPs have frequently drawn parallels between ArriveCan and another Liberal impropriety—the sponsorship scandal which broke in the early 2000s—even though many experts agree the circumstances and consequences of each government spending scandal are distinct.

The sponsorship scandal—sometimes called AdScam or Sponsorgate—brought to light revelations that the Liberal government misappropriated funds meant for promoting national unity in Quebec after the 1995 sovereignty referendum. The issue followed then-prime minister Jean Chrétien during his latter years in office, and plagued the short-lived government of his successor Paul Martin.

What ArriveCan and AdScam have in common is the significant amount of taxpayer money at stake, and a major lack of oversight and accountability—both of which erode public trust, experts agree.

“ArriveCan is a different scandal in Canada compared to other procurement issues,” Gilles LeVasseur told The Hill Times by email. LeVasseur is a professor of management and law at the University of Ottawa who has overseen public and private-sector projects.

“The failure primarily stems from poor project management by senior civil servants who did not properly apply protocols and appropriate project management norms,” he added. “The political system was not adequately informed at the initial stage, and the project expanded due to the complexity of information technology components and a lack of proper oversight.”

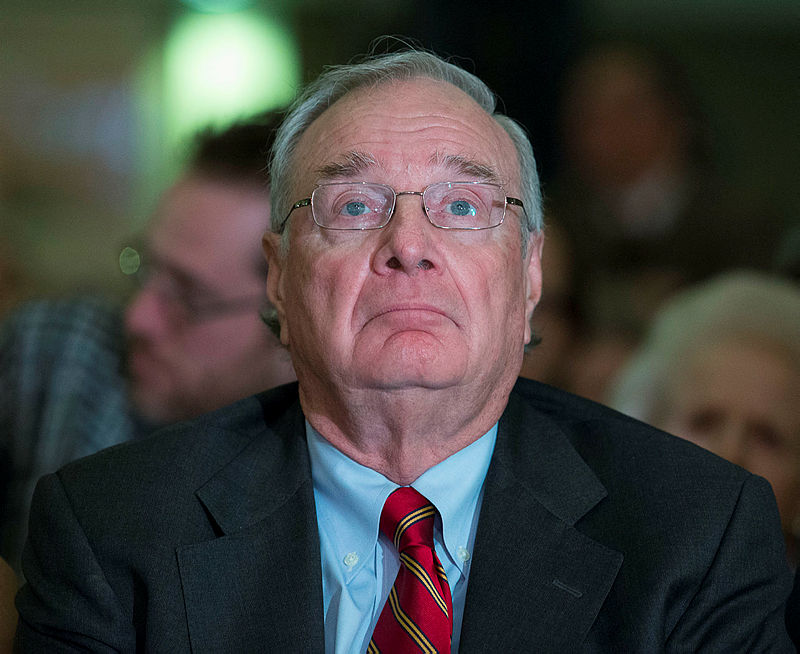

Former Privy Council clerk Michael Wernick echoed that assessment.

“ArriveCan is not like the sponsorship scandal because there is no evidence of a partisan political dimension to it,” Wernick said by email.

“The case can be seen as revealing big weaknesses in the overall procurement system, so the question now is what solutions are being proposed to address them,” he said, adding other procurement controversies, like the 1980s Airbus Affair, present a different set of lessons and course corrections.

According to Wernick, the biggest problem with procurement is that “politicians have loaded it up with about a dozen policy goals,” such as “regional benefits, supporting small businesses, Indigenous and Black entrepreneurs, stimulating technology firms, green procurement, reducing plastic waste, and more.”

Retired senior RCMP investigator Patrice Poitevin said the ArriveCan application, like past procurement failures, “revealed inadequate supervision and control mechanisms in the procurement process.”

“These consistently erode public trust in government institutions and their ability to manage public resources effectively,” Poitevin told The Hill Times.

Poitevin is the co-founder and executive director of the not-for-profit Canadian Centre of Excellence for Anti-Corruption. He consulted for the federal government’s preparation of the Guide to Best Practices in Integrity in Public Procurement, published in 2019.

“It seems to me there are huge gaps that should have been addressed. And [in the case of ArriveCan] it’s not political. This is systemic,” said Poitevin.

Poitevin argued the list of scandals have common issues such as lack of oversight and transparency, failures in complex project management, lack of expertise, and cost overruns—and they persist despite years of calls to improve the government’s procurement system.

“It’s not our first barbecue here. This is not new,” he said. “But if we repeat the same mistakes, obviously we’re not doing the right thing.”

Poitevin said Canada needs to address these issues revealed in past problematic procurement projects “because we’re not going to change anything unless you have the type of best practices that other countries or companies have put in place.”

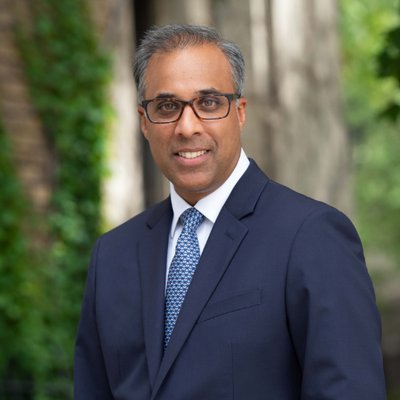

These unsuccessful projects hurt public confidence, said Sahir Khan, a former assistant parliamentary budget officer.

“It tears at public trust,” said Khan, who is now the vice-president of the Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy at the University of Ottawa.

Khan argued that “the lack of capacity, and the will to execute complex projects within the public service is where a lot of the issues are rooted.” The former PBO staffer said a scandal like ArriveCan alone would not be enough to topple a governing party, but not delivering on promises would hurt the government.

“If the public doesn’t feel confident that you’re delivering on the results and you’re just writing really big cheques, you are going to struggle politically with that,” he added.

Khan said governments often overlook the complexities of public procurement, ignore its intricacies, and fail to realize that project execution is as important to the public as the initial project idea. This becomes increasingly critical the longer a government remains in power, he argued.

“And, often, politicians don’t want to hear that something is really not fully baked before it gets rolled out. And then once they get going, no one has an incentive to say there’s a problem,” he added.

Procurement failures, including the shipbuilding strategy and the problem-plagued Phoenix pay system, which Khan tracked closely during his time at the PBO, “did not have substantiated business cases when they launched,” he said. This led to cost overruns and issues with the rollout of the projects, which in turn prompted political repercussions, Khan explained.

“You either have to get it right at the front end, or you’re never going to get them right. These projects usually don’t have really good business cases at the start, nor do they have experienced people delivering or skills to do the due diligence,” he said.

Khan said the federal government failed to build the internal capacity and expertise to roll out major projects in the public service.

He said that when this Liberal government got elected, they thought, “We’ll put in deliverology”—the name of a management theory championed by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau (Papineau, Que.) in the early years of his government.

“People think about these gimmicks as opposed to [asking], ‘Do we give deputy ministers who’ve never done these things the responsibility for rolling them out?’” he said.

Khan noted that government spending relative to GDP has increased to between 15 and 16 per cent, up from the 12 to 13 per cent range seen under the Liberals with Chrétien and Martin, and the Conservatives under Stephen Harper.

Khan said the increase means Trudeau’s government faces higher expectations for the successful delivery of projects, and an increased burden of accountability—particularly for progressive governments, which often promise to invest more taxpayer money.

“The real issue is governments have a hard time raising taxes when the public doesn’t have confidence in the way they spend money. It’s really quite simple that way,” he said.

Do voters care about procurement scandals?

Khan and his co-writer Helaina Gaspard’s 2017 analysis shows that, historically, fiscal promises have not impacted election outcomes. Their research revealed that voters instead put more importance on whether taxpayer money is being spent well, rather than notions like fiscal balance or deficits.

“When we looked at operating efficiency, that’s where all this procurement stuff lives, it turns out it actually does matter. Our thesis is that [spending scandals] actually have a really big impact with voters, particularly when a government has been in power for some time,” explained Khan.

“Voters tend to lose patience by the third term. You can’t campaign on inspiration anymore. It’s perspiration that matters,” he said. The Trudeau Liberals have won three elections, first by majority in 2015, followed by successive minority Parliaments in 2019 and 2021.

Jordan Paquet, a senior consultant with Bluesky Strategy Group, said “a general lack of oversight and accountability” often leads to continuous spending and procurement scandals.

“There are clear rules in place, they just need to be followed. The federal procurement process is so complex and thorough for a reason—it’s to avoid these types of scandals,” he told The Hill Times.

“Scandals hit any government no matter the political stripe,” Paquet said. “The Liberals have struggled with either a real or perceived lack of transparency on some of the major ones, which sticks in the minds of voters.”

Paquet highlighted the broader political implications of spending scandals on public trust. “These scandals certainly work to solidify [the existing] distrust. That leads to Canadians further disengaging from the political process, including voting.”

“Previous spending scandals in Canada have resulted in high-profile resignations, criminal prosecutions, and contributed to electoral defeats,” and the sponsorship scandal is one example with real consequences that “really stands out,” according to Paquet.

“Affordability wasn’t top of mind as a political issue back then, so trust in government became a predominant issue in the subsequent election campaigns that saw the Conservatives remove the Liberals from power,” he explained.

Paquet suggested that while the ArriveCan debacle has further eroded trust in the Liberal government—already struggling in polls—the political fallout has yet to reach the same extent as the sponsorship scandal, despite similarities in issues of lack of oversight and accountability.

A July 25 poll by Abacus Data suggests that, if an election were held today, 42 per cent of committed supporters would vote Conservative, while 23 per cent would vote Liberal.

Canadians place more trust in the police (67 per cent), other people (66 per cent), and courts and the judicial system (62 per cent) than in the federal government (49 per cent).

Paquet argued that the rules around procurement are “very clear and just need to be followed,”

“When an issue inevitably breaks, complete transparency is the best strategy. Otherwise, it will remain in the headlines and rightly haunt a government come election time,” he said.

ikoca@hilltimes.com

The Hill Times

Procurement problems from the past five decades

Airbus Affair

The Airbus Affair is a political scandal that began in 1988, and concluded in 2010. Under the government of then-Progressive Conservative prime minister Brian Mulroney, Air Canada—which was then a Crown corporation—purchased a fleet of Airbus A320 aircraft for $1.8-billion. An RCMP investigation looked into allegations of the prime minister accepting bribes from Karlheinz Schreiber, a German-Canadian businessman and lobbyist. Mulroney denied the allegations, and sued the Canadian government, but a public inquiry—the Oliphant Commission—concluded in 2010 that Mulroney received $225,000 in bribes. Mulroney admitted to receiving cash from Schreiber, but denied it was connected to the Airbus deal. The scandal highlighted issues of transparency and ethics in government procurement.

Human Resources Development Canada scandal

The Human Resources Development Canada (HRDC) scandal of 2000 unfolded after an internal audit raised serious questions about $1-billion in grants and assistance from that department. The audit found inadequate documentation, poor oversight, and funds allocated without clear objectives, with some grants awarded to organizations with ties to the Liberal Party. Then-human resources minister Jane Stewart was pressured to resign, but she remained in her position, committing to reforms aimed at improving oversight and accountability in HRDC’s grant programs. The scandal raised concerns about accountability and governance in federal grant programs.

Sponsorship Scandal

The sponsorship scandal, also known as AdScam, was a major political scandal in the early 2000s under Liberal prime minister Jean Chrétien. A sponsorship program was launched to increase the federal government’s presence in Quebec through advertisements and cultural events amid the 1995 Quebec referendum on sovereignty. Media coverage and an investigation by then-auditor general Sheila Fraser revealed that funds were allocated to Liberal-friendly advertising firms and consultants who, in return, made donations to the Liberal Party of Canada. A public inquiry led by Quebec Superior Court justice John Gomery revealed that ad agency executives and Liberal Party officials had corruptly handled more than $300-million. Five people were found guilty of fraud. The scandal damaged the reputation of the Liberal Party, including Chrétien and his successor Paul Martin. It contributed to the Liberal Party’s defeat in the 2006 federal election, paving the way for the Conservatives to take power under Stephen Harper.

F-35 procurement

In 2012, the Conservative government announced it would start a procurement process to replace Canada’s aging fleet of CF-18s with Lockheed Martin’s F-35 fighter jets. Initially, the projected cost for 65 fighter jets was estimated at around $16-billion, which mushroomed to $45-billion due to overruns and delays. This disparity between the estimates and actual costs prompted criticisms of mismanagement and lack of transparency, and led the government to abandon the procurement process. Michael Ferguson, the auditor general at the time, criticized the government for lowballing the costs and not following proper procurement protocols. The events led to a re-evaluation of Canada’s defence procurement strategy.

Davie Shipyard Scandal

Davie Shipyard, a major Canadian shipbuilding company, was awarded a $668-million contract in 2015 to convert a civilian vessel into an interim supply ship for the Royal Canadian Navy. This contract, known as Project Resolve, was part of the Navy’s effort to amp up its supply ship capability after the retirement of its aging vessels.

Vice-Admiral Mark Norman, the second-highest-ranking officer in the Canadian military at the time, was accused of leaking confidential information to Davie Shipyard about the Liberal government’s plans to delay or cancel the contract, which had been awarded by the previous Conservative government. The alleged leaks were intended to pressure the government to proceed with the contract to avoid political backlash and potential job losses.

In 2017, the RCMP launched an investigation into the allegations, which led to Norman’s suspension and being charged with breach of trust in March 2018. Norman maintained his position, arguing that his actions were in the best interest of the Navy, and that he was being unfairly targeted. In May 2019, the charges against the vice-admiral were dropped after the Crown concluded that there was no reasonable prospect of conviction, citing new information provided by the defence. Norman was reinstated to the military, and received an apology from the House of Commons.

SNC-Lavalin Affair

In 2015, the RCMP laid corruption and fraud charges against Montreal-based engineering and construction firm SNC-Lavalin over allegations of bribery to secure government contracts in Libya. Then-Liberal attorney general Jody Wilson-Raybould later revealed she faced pressure from Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, his handlers, and top bureaucrats to offer a deferred prosecution agreement (DPA) to the company, which would allow it to avoid a criminal trial. In 2019, then-ethics commissioner Mario Dion released a damning report on the ethics violation, stating that Trudeau and his officials had improperly sought to influence Wilson-Raybould’s decision.

Wilson-Raybould resigned from the cabinet in February 2019. Following her resignation, Jane Philpott, then-president of the Treasury Board and minister of digital government, also resigned in solidarity.

The affair made headlines for months in 2019, leading up to that year’s federal election. Key people named in the affair resigned, including Gerald Butts, then-principal secretary to Trudeau, and Michael Wernick, then-Privy Council clerk, who announced his retirement. The SNC-Lavalin affair had significant political fallout, raising concerns about the independence of the judiciary, and the potential for political interference in legal matters. Trudeau’s Liberal Party was re-elected in the 2019 election, but was reduced to a minority government.

The scandal also brought attention to the use of DPAs in Canada, and sparked a national debate about corporate accountability and the ethical conduct of public officials. SNC-Lavalin ultimately settled the case in December 2019 by pleading guilty to fraud and agreeing to pay a $280-million fine.

Phoenix Pay System

The Phoenix pay system administers the federal government payroll. The IBM-made system was established under the Harper Conservative government. IBM was awarded the contract for the new pay system in June 2011, through Public Services and Procurement Canada’s (PSPC) competitive process. The program was rolled out in 2016 by the Trudeau Liberal government, but it has been problem-plagued ever since. Tens of thousands of federal employees have experienced issues such as underpayments, overpayments, and non-payment of salaries. The government has faced severe criticism and legal challenges, spending billions of dollars in attempts to fix the system and compensate affected workers. Government records show that there have been 50 amendments to the initial Phoenix contract—valued at $309-million—to fix errors for a total contract value of $545-million. The ongoing issues with the system have led to questions about the government’s capacity to manage large-scale IT projects, and have resulted in significant financial and morale impacts on federal employees.

ArriveCan Scandal

The ArriveCan application was launched in April 2020 for international travellers to submit their COVID-19-related information electronically at border crossings. The emergency procurement of the app has been under scrutiny since the fall of 2022 due its soaring price tag, which Canada’s auditor general estimated cost $59.5-million. The allegations of misconduct involving some of the contractors and public servants who worked on the app’s procurement further intensified scrutiny.

GC Strategies was the primary contractor for the application, and received an estimated $19.1-million for its work, which did not involve the app’s actual development or maintenance. While the company’s co-founders deny any wrongdoing, their two-person IT staffing firm has been at the centre of a dozen independent probes including one by the RCMP.

LICENSING

LICENSING PODCAST

PODCAST ALERTS

ALERTS