First Nations, Inuit, and Métis leaders lay out major asks for re-elected Liberal government

With the historic inclusion of three Indigenous ministers in cabinet, Assembly of First Nations National Chief Cindy Woodhouse Nepinak says the governing Liberals can approach the upcoming parliamentary session as an unprecedented opportunity to address unresolved issues facing Indigenous Peoples.

Two of the top issues facing First Nations communities are the absence of clean drinking water and proper policing on reserves, said Woodhouse Nepinak. She said Mandy Gull-Masty (Abitibi-Baie-James-Nunavik-Eeyou, Que.)—the first Indigenous minister overseeing Indigenous services—Northern and Arctic Affairs Minister Rebecca Chartrand (Churchill-Keewatinook Aski, Man.), and Buckley Belanger (Desnethé-Missinippi-Churchill River, Sask.), secretary of state for rural development, can help advance those files in cabinet.

Woodhouse Nepinak is on the lookout for the return of a bill that died on the Order Paper in last Parliament: the First Nations Clean Water Act, which would have set drinking-water standards in First Nations communities and established a First Nations Water Commission.

Woodhouse Nepinak said Bill C-61 was “a missed opportunity to address” a crisis in which 38 drinking-water advisories in 36 First Nations remained in effect as of May 8, according to Indigenous Services Canada. In 2015, then-prime minister Justin Trudeau vowed to end all long-term drinking water advisories on reserves by 2021.

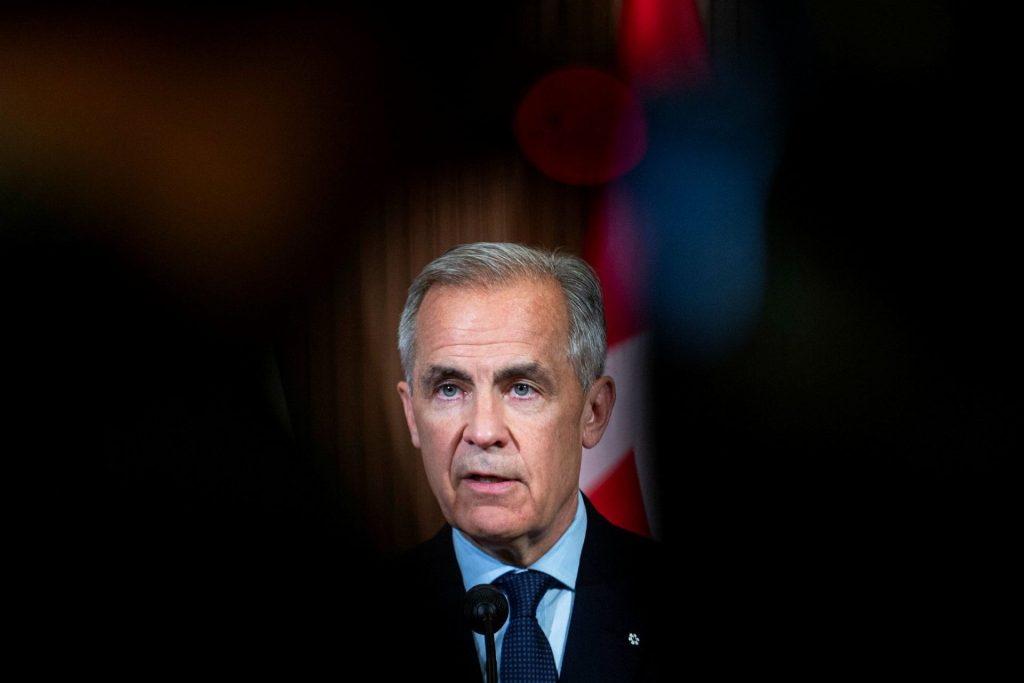

Now she said it’s time for Prime Minister Mark Carney’s (Nepean, Ont.) government to make the legislation’s return a priority.

During the election campaign in April, Carney told an AFN forum that his government would reintroduce C-61 and take First Nations guidance on creating a water commission to ensure they have the capacity for developing and maintaining the required infrastructure.

Beyond seeking relief from Parliament, First Nations have gone to the courts to gain access to clean drinking water. In 2021, First Nations and Ottawa agreed to an $8-billion settlement related to communities that were subject to drinking-water advisories between 1995 and 2021.

In 2022, the Federal Court also approved a class action brought forward by the Shamattawa First Nation in northern Manitoba, related to drinking-water advisories that lasted one year since 2020.

In its statement of defence, the federal government argued that “Canada does not owe the plaintiffs a general fiduciary duty as asserted to provide or fund water infrastructure on reserve. … Canada does not owe any legal obligations or duties to operate and maintain the plaintiffs’ water systems.”

Problems with public safety on reserves have also ended up in court.

Last November, in an 8-1 ruling, the Supreme Court of Canada held that the Quebec government needs to provide further funding for the Pekuakamiulnuatsh First Nation’s police force in the province after being ordered to do so by the Quebec Court of Appeal in 2022.

Woodhouse Nepinak said the federal government needs to allow First Nations to “take control of their own public safety because the models we now have are not working.”

“What other town or city in the country would put up with not having policing services within their communities? But unfortunately, First Nations have to tolerate that every day,” said the national chief, who is the great-great-great-granddaughter of Richard Woodhouse, who signed Treaty 2 in 1871—the second Aboriginal treaty with the Crown since Confederation.

During the election, the AFN called on the next government to commit to legislation that affirms First Nations’ jurisdiction over on-reserve policing, recognizes it as an essential service, and includes provides long-term funding.

At the AFN’s election forum, Carney said “we want to move to self-administered First Nation policing services.”

The assembly was also involved in a class action that in 2023 resulted in a Federal Court-approved, $23-billion settlement for about 300,000 First Nations children and their families regarding Canada’s chronic under-funding of on-reserve child welfare services between 1991 and 2022.

“We don’t always want to be in court,” said Woodhouse Nepinak. “Why don’t we just get to the table and work out things so we’re not always fighting each other in court?”

Leaders want to be at premiers’ table

Carney is meeting with premiers in Saskatoon, Sask., on June 2, and Indigenous leaders should be at the same table to discuss issues affecting their communities, she said, and not, “at the little kiddies’ table the day before a meeting of the first ministers” as her predecessors faced.

“Those days have to be gone,” she said. “We have colonialism at our doorstep from people like [United States] President [Donald] Trump pushing it towards Canada—and Canada should not continue to do that against First Peoples.”

“We’re stronger together.”

Natan Obed, president of the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK), echoed those frustrations. His group represents Canada’s 70,000 Inuit who live on 40 per cent of this country’s land mass and along 72 per cent of its coastline

“We are partners in Confederation, whether provincial or territorial premiers like it or not,” said Obed, noting that he has already had discussions with ministers Gull-Masty and Chartrand.

“It’s not been the Government of Canada that has been actively excluding us from these conversations. It has been provinces and territories.”

When asked about the provincial-territorial pushback, Obed said he believes the premiers view first ministers’ meetings as “privileged space with the prime minister, and often see First Nations, Inuit, and Métis issues as being separate in governance.”

“We share the governance of this country, and Inuit very explicitly have modern treaties and constitutionally-protected space,” said Obed, who has headed the ITK since 2015. “We have self-governments, we have administration of public funds that we provide to citizens just like provinces and territories do. But there is a lack of interest in treating national Indigenous leaders as if we play a significant role within the confederation of this country,” which he described as “a vestige of a more colonial and less-inclusive time in the country.”

Obed, who also serves as acting president of the Inuit Circumpolar Council Canada, is determined to change that.

He recently sent Carney a letter calling for a first ministers’ meeting on the Arctic with ITK participation.

The Fredericton-born, 49-year-old Inuk, who was raised in Nain, Nunatsiavut (an Inuit autonomous region in northern Labrador), said the people of the Inuit Nunangat (homeland) want to be partners in conversations involving Northern defence, sovereignty, infrastructure investments, and the militarization of the Arctic and matters involving it with other countries.

He hopes the Carney government will focus on those issues through the lens of the Inuit Nunangat Policy, which was created in 2023 during the Trudeau government, and through the Inuit-Crown Partnership Committee in which the prime minister and the ITK president are meant to co-chair an annual meeting.

Arctic defence on ITK’s radar

The national Inuit organization, formed in 1971, has several asks of the federal government during the upcoming parliamentary session. Chief among them is that any economic initiatives intended “to ease the worst outcomes of the tariff war” with the U.S. don’t add to the already high costs residents in the 51 Inuit communities face.

Obed explained that only two communities in the Northwest Territories—Inuvik and Tuktoyaktuk—have all-weather access roads. The rest are “fly-in, fly-out” communities, “which makes things much more expensive.”

Beyond the economic threat posed by the Trump administration, Obed made note of the American president’s frequent references to acquiring Greenland, which is in close proximity to Canada, and in some cases it’s less than 100 kilometres away.

“We share a common society and culture, and Canada should be considering the Arctic element of the U.S. expansionist rhetoric,” he said.

During the election campaign, the Liberals pledged to “work closely with Arctic and Northern Indigenous leadership as partners, in defence and security investments that respect their rights, incorporate traditional knowledge, and ensure community priorities are reflected.”

Obed said that during the 1940s and 1950s, the Inuit Nunangat “became a key and vital part” of the American and Canadian security apparatus at the end of the Second World War.

“But the first time that happened, we weren’t a part of it at all.”

Through treaties in place, Obed said the ITK would like to collaborate with the federal government on “defending our borders and ensuring that the infrastructure that we need to do that is not only helpful for Canada and its allies, but also essential for Inuit and our communities.”

He said that the Inuit need extends to housing infrastructure. In March and before the federal election, Carney announced during a trip to Iqaluit that his government would invest nearly $66-million to build, renovate, and repair homes across Nunavut.

Obed also said he hopes the Liberals will honour their campaign commitments to increase investments for Indigenous mental health and “partner with Inuit to eliminate tuberculosis in Inuit Nunangat by 2030.”

Métis National Council urges greater investment

Victoria Pruden, president of the 42-year-old Métis National Council, said the MNC has several priorities for the new Parliament.

“We call for targeted investments in distinctions-based tools to support capital access, procurement readiness, and skills development for Métis businesses,” which Pruden said includes a dedicated Métis stream within the Indigenous Loan Guarantee Program.

She said that in light of growing demand from a young and expanding Métis population, the MNC also seeks “a renewed commitment and increased investment” in the Métis Nation Post-Secondary Education Strategy that is run through Indigenous Services Canada and which received $362-million over 10 years in the 2019 federal budget.

Pruden, who was elected MNC president last December, also wants increased federal investment “to support sustainable energy and infrastructure, low-carbon economic development, and prosperity and emergency management and climate resilience” across the Métis homeland in Canada, which includes the Prairie provinces, and extends into contiguous parts of Ontario, British Columbia and the Northwest Territories.

Those goals are identified in the Métis Nation Climate Leadership Agenda that was co-developed by the MNC, the five Métis governments (in B.C., Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Ontario), Environment and Climate Change Canada, and Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada.

Pruden said the MNC wants the Carney government to convene a Crown-Métis Nation Summit (the last one was held with Trudeau in 2023) to “reset priorities and implement outstanding commitments in areas such as justice, health and emergency management” under the Canada-Métis Nation Accord signed in 2017.

The national council is also calling for continued negotiation and implementation of self-government and treaties with Métis governments, said Pruden.

“Building a more inclusive and prosperous Canada requires working in full partnership with Indigenous governments.”

The Hill Times

LICENSING

LICENSING PODCAST

PODCAST ALERTS

ALERTS