Liberals to push ahead with pharmacare, but program’s fate under Conservatives is unclear

Health Minister Kamal Khera says a re-elected Liberal government would work to get on board the nine provinces and territories that have not signed pharmacare bilateral agreements. But what Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre would do with the program if his party forms the next government is unknown.

The single-payer pharmacare program—focusing on specific pharmaceuticals for diabetes and contraception—is one of the landmark policies to come out of the Liberal-NDP supply-and-confidence agreement that was negotiated by then-Liberal prime minister Justin Trudeau and NDP Leader Jagmeet Singh, who is running for re-election in Burnaby South, B.C. After pharmacare legislation was passed in October 2024, Trudeau’s government signed bilateral agreements for funding with Manitoba, British Columbia, and Prince Edward Island between Feb. 27 and March 7, 2025.

Although four agreements have been signed, programs have not yet been implemented. Prince Edward Island will be the first province to make the federal coverage available to its residents on May 1, 2025. And with a deadline of March 2026, B.C. has the longest timeline for implementing the coverage at this point.

Until recently, it was unclear whether single-payer pharmacare—where medications are covered under a government-funded program as opposed to a mix of public and private insurance—would go ahead under a Liberal government led by finance-focused Mark Carney, who won the Liberal leadership on March 9.

But between Carney’s swearing-in as prime minister on March 14 and when the general election was called on March 23, Yukon signed on.

The day before the election call, Canada’s new health minister pointed to the Yukon agreement to signal what a Carney government would do about pharmacare. Khera, who represents Brampton West, Ont., and was named health minister on March 14, said pharmacare is a priority for the Liberals.

“Under the Carney government, we were able to sign an agreement just two days ago with Yukon, and we have been able to sign four agreements with different provinces and territories already,” Khera said at the March 22 press conference in response to a question from Hill Times Health about whether agreements would continue to move ahead if her party is re-elected.

“We will continue to make sure we deliver for Canadians, whether it’s diabetes medication that is changing lives [or] whether it is oral contraception that’s changing lives.”

Neither Poilievre—who is running in Carleton, Ont., during his first campaign as party leader—nor his health critic, Dr. Stephen Ellis—running for re-election in Cumberland-Colchester, N.S.—responded to a request for comment as to whether their party would go ahead with a single-payer pharmacare program if it were to form the next government. The offices of both MPs received an email on March 19, and a follow-up on March 20. Neither email was acknowledged.

The Conservative Party has in the past made it clear that they do not support the single-payer model, voting against the Pharmacare Act (then Bill C-64) at both second and third readings. Poilievre also said during a House of Commons debate on Sept. 24, 2024, that he “will reject the radical plan for a ‘single-payer’ drug plan.”

During a March 25 press conference in Vaughan, Ont., Poilievre was asked by a reporter if he would “roll back” dental care and pharmacare programs if his party were to form the next government.

“We will protect these programs and no one who has them will lose them,” Poilievre replied. “I would note, let’s go through them one at a time. We will make sure that nobody loses their dental care.”

He then turned to the subject of child care, saying that Conservatives believe there should be more affordable child care. He ended his response by touting his party’s plan to make it easier for foreign health care professionals to become licensed to work in their field in Canada. He did not make any specific references to pharmacare.

Unsurprisingly, the NDP is fully committed to continuing negotiations if it were to form the next government.

NDP health critic Peter Julian said in a voicemail on March 19 that his party would go ahead with pharmacare and other health bilateral agreements.

“A vote for the NDP in the next election really is a vote for action, implementing these things, rather than dangling them before the electorate as a carrot,” said Julian, who is running in New Westminster–Burnaby–Maillardville, B.C., aiming to return to Parliament for an eighth term.

As of March 24, the Carney Liberals and Poilievre Conservatives were neck-and-neck in popularity—39.6 per cent to 37.3 per cent, respectively, according to CBC News’ Poll Tracker, which averages the results from multiple pollsters. Singh’s NDP was lagging in third place with 10.1 per cent.

If an election were held on March 25, which is only the third day of the 37-day campaign, the Liberals would win a majority government with 183 seats, the Conservatives would form the official opposition with 130 seats. The NDP would be down to just four seats, a far cry from the 25 seats in the 2021 contest, and well off from the 12 MPs needed to form official party status.

New government could ‘reverse, undo, or renegotiate anything’

Bilateral funding for pharmacare—worth a total of $1.5 billion—is one of two sets of health agreements that were not signed by all provinces and territories before the election was called. The Liberals under Trudeau were also negotiating agreements to help provinces and territories fund personal support workers, and completed three deals before Carney took over earlier this month. Budget 2023 earmarked $1.7-billion over five years to aid hourly wage increases for them “and related professions.”

A third set of agreements—$1.4 billion to help provinces pay for drugs for rare diseases—was completed on March 21, just two days before Carney asked the governor general to dissolve Parliament.

Now that Canada is in campaign mode, Health Canada cannot finalize any other agreements. Following an election, it will be up to the newly-elected government to decide whether to keep already-signed agreements and continue negotiations on others, or whether to change course.

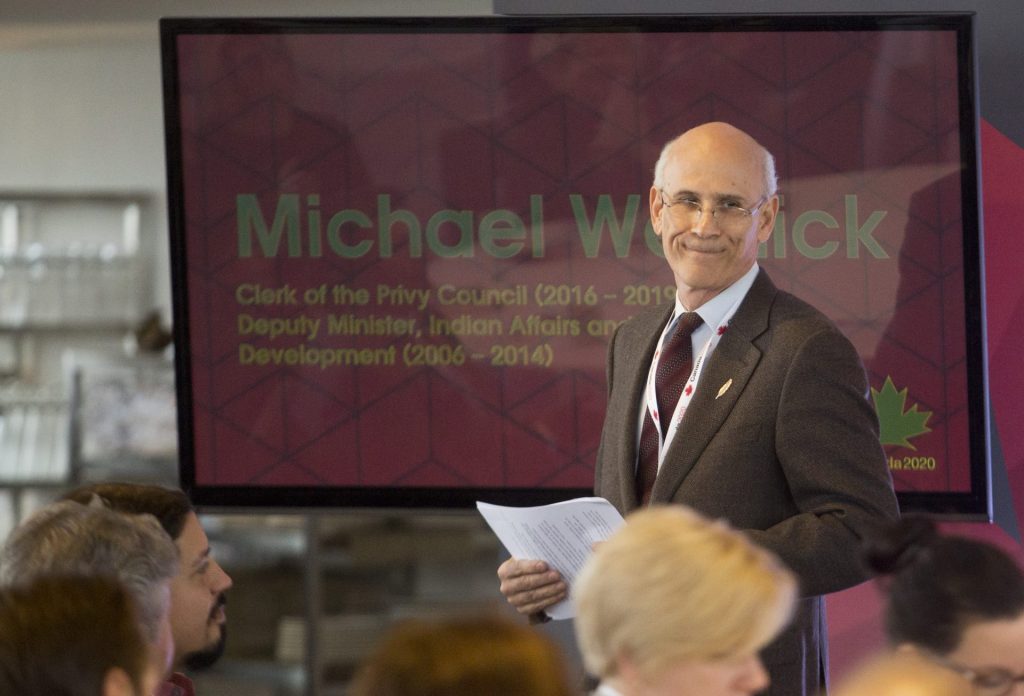

Former Privy Council clerk Michael Wernick said that agreements signed by one government are binding if there is a change in the country’s leadership, but a new government can also make changes.

“The next government and Parliament can basically reverse, undo, or renegotiate anything it wants to,” said Wernick during a March 19 phone interview. “It comes down to the specific language in terms of termination clauses, compensation, penalties, what courts would find was reasonable notice, what courts would find was reasonable compensation, and so on.”

Jill Pilgrim, who worked for former Liberal health minister Mark Holland, said that the decision of whether to honour pre-existing agreements would be up to the government of the day.

“I know that Pierre Poilievre has stated in the past that [the Conservatives] would not support national pharmacare, but that was before any of the agreements were finalized. There hasn’t really been much sense on whether they would honour those agreements,” said Pilgrim, now a senior consultant at Santis Health, during a March 20 interview.

A tale of provincial haves and have-nots

Still, provinces and territories are likely to feel differently about whether the next federal government should move ahead, according to a health policy expert and a former bureaucrat.

Tom McIntosh, a professor of politics and international studies at the University of Regina, said that the existence of a program for some jurisdictions and not others “will not sit well with the provinces.”

“Even those that would prefer that the federal government stay out of their business, they still want the cash, and so there may be pressure to come to finish that process if [the federal government] can’t get out of the existing agreements,” McIntosh, who specializes in Canadian politics and health policy, told Hill Time Health on March 18.

He added that provinces who hadn’t yet signed on may have their spending plans impacted if they don’t receive the funding from these agreements.

Marcel Saulnier, who spent 12 years in senior roles at Health Canada, said that “fairness across the federation is the real driver” when it comes to negotiating these agreements.

“I don’t think the next government could get away with just having a set of agreements with some jurisdictions and not with others,” said Saulnier, now a senior adviser at Santis Health, in a March 18 interview.

Pilgrim, who worked on bilateral funding agreements for health systems and for seniors while in Holland’s office, said that staffers and the government go into these discussions with the goal of attempting to finalize agreements with all provinces and territories.

“I think there is a risk there that the new government—whoever that may be—will not, and that could create some friction,” she said.

Bilateral agreements include standardized language that allow for changes that can be initiated by either of the signatories. These particular agreements include a termination clause that states that either party can choose to end the deal “if the terms of this agreement are breached,” and if written notice is provided six months in advance. Agreements can also be amended “at any time by mutual consent of the parties.”

Saulnier said a government that does not want to move ahead with the deals has the option of keeping the existing agreements, but changing the approach set by the Trudeau Liberals.

Those bilateral agreements have been specific about the areas of health (such as mental health, primary care, and home care) where federal dollars are meant to be spent. Provinces and territories have typically been required to report on outcomes from the federal spending.

If the next government doesn’t agree with the Trudeau government’s conditions, Saulnier said it could choose to provide the previously-promised money to provinces and territories through a federal transfer arrangement, and avoid the “policing” approach that had been present in these agreements.

“I think they would have to get the agreement of the jurisdiction to do that because it would … kind of be a breach of the agreement … [but] I don’t think too many provinces would complain that strings are being taken off of the money,” Saulnier said.

But a new government could also just undo what the Trudeau Liberals put in place.

Wernick pointed out that Stephen Harper’s Conservatives replaced Liberal prime minister Paul Martin’s plan for child care agreements.

The Liberal government had negotiated child care funding with 10 provinces between 2003 and 2005. After the 2006 election, the new Conservative government cancelled the deals and replaced that funding with benefit payments sent directly to parents.

Wernick noted that once Trudeau was elected in 2015, he replaced Harper’s child benefit program with a new program.

This piece was first published on Hill Times Health. Tessie Sanci is the executive editor of the website, which provides in-depth coverage of federal health policy. Click here to register online for a free trial.

The Hill Times

This article was corrected on April 1, 2025 to clarify Tom McIntosh’s professional title. McIntosh spoke to Hill Times Health in his capacity as a professor of politics and international studies, and not in his other role as associate dean at the University of Regina.

LICENSING

LICENSING PODCAST

PODCAST ALERTS

ALERTS