Rebuild underway: fresh peek inside Centre Block offers up new details

Media got a fresh look inside the Centre Block construction site on Nov. 14, with new details and a new tour stop offered up along the way.

The Centre Block Rehabilitation Project being led by Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC) includes both the renovation of the 100-year-old building, as well as construction of a new underground Parliament Welcome Centre (PWC).

Along with heritage restoration, the project will see Centre Block modernized with new building systems, and brought up to par with modern fire safety and universal accessibility requirements. Improved energy efficiency is also a project priority, and PSPC is aiming to ultimately reduce the building’s energy use by roughly 65 per cent. Pre-renovations, it was one of the worst-performing buildings in PSPC’s portfolio in terms of energy efficiency.

Centre Block has been closed for construction since the end of 2018, and with demolition and hazardous material abatement work complete, “we are now into the phase of rebuilding,” Siavash Mohajer, PSPC’s senior director of the Centre Block Rehabilitation Program, told reporters gathered for the “second annual media tour.”

Despite higher-than-anticipated rates of inflation since PSPC first released project estimates in June 2021, Mohajer confirmed that work continues to “track” in line with the projected $4.5- to $5-billion price tag.

“Inflation—or escalation, as we call it—is a pressure,” said Mohajer. “There are various pressures on our cost, but we planned for it to some extent. Obviously we didn’t expect eight per cent inflation when we put together the budgets, but we carried enough that we’re able to absorb these pressures.”

Mohajer highlighted the complex work ongoing in Centre Block’s basement in preparation for excavations that will happen underneath the historic structure—both to connect the building to the PWC, and to install base-isolation seismic upgrades—as another “pressure” on project costs.

“So far, when we put together all these pressures and what we can see in the future, we’re still tracking within that [cost estimate range],” he said.

But “time is money, and so when you’re having monetary pressures it translates into time pressure, as well.”

“We are seeing pressures on the schedule, however everything is still tracking to finish in that 2030-31 range in terms of construction,” said Mohajer.

The department has previously noted that once construction finishes, it’ll be another year—roughly—before the building is ready to be fully reoccupied.

The finalization of conceptual design plans for Centre Block—expected by the fall of 2025—will be a “key checkpoint” in confirming “that we’re still able to absorb all these pressures,” noted Mohajer.

As of Sept. 30, a total of $975-million had been spent on the project to date.

Along with work to prepare for structural upgrades throughout Centre Block—including installation of a new, slightly raised roof, as well as new elevator banks, stairwells, and more—the work ongoing on the building’s first and basement levels is currently a main project focus.

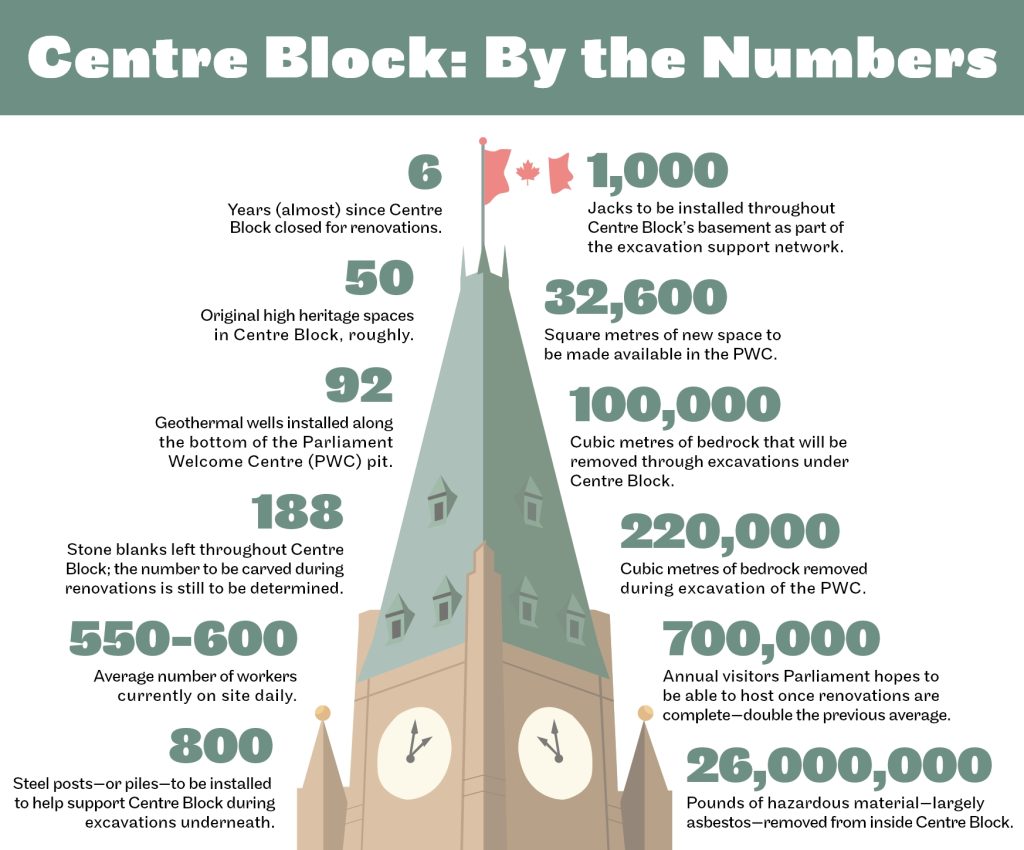

As has been previously detailed by The Hill Times, a lot of work needs to happen to stabilize Centre Block ahead of excavations, including installation of a network of 800 steel posts, structural steel supports, and concrete sandwich beams, and replacement of the building’s level 1 slab. About 85 per cent of those steel posts—or piles—are now in place.

Excavation under Centre Block is projected to start next spring, and will involve removal of an estimated 100,000 cubic metres of bedrock to dig down roughly 23 metres—in line with the depth of the welcome centre pit.

Digging will start in the building’s courtyards—starting in the west—and eventually move south to connect to the welcome centre through openings on either side of the Peace Tower.

Mohajer has previously said that at least 50 per cent of the building’s slab needs to be replaced before the building’s load will begin its transfer onto the support network in advance of digging.

PSPC’s second-quarter progress report this year flagged some delays in slab replacement work—which first got underway in the spring of 2023—with the department having failed to meet its target of replacing 20 to 25 per cent of the building’s slab by June 30. Progress has since reached the 25 per cent mark.

Speaking to those delays, Mohajer highlighted the “complexities” and “physical constraints” of the space: “The work is complex [and] in small, confined spaces—so you can’t throw more people at it—and the sequence of it is very prescribed, and so we can only move as fast as we are physically allowed.”

“We are working with the construction manager and structural engineers to see if we can change things—re-sequence things—to continue with our excavation while we progress with the level 1 slab [replacement], and right now all signs are positive,” he said.

Unlike the welcome centre pit—where workers were able to blast through roughly 220,000 cubic metres of bedrock—digging under Centre Block will be a more delicate operation, and will involve use of remote-operated machines.

“We’ve got to be very careful and meticulous on how we remove the bedrock,” Bill Coleman, the structural lead for construction manager PCL/EllisDon, told the tour.

Multiple systems are in place to track the building’s movement during this work, including liquid and laser level monitoring systems, a vibration monitoring system that helps to identify the source of vibrations, and temperature monitors to establish a baseline of the building’s natural expansion and contraction and help differentiate movement caused by construction, he explained.

“We’re trying to keep it under three millimetres of vertical movement, and in some areas one millimetre, which is very, very hard to do but we have the best of the best helping us do this,” said Coleman.

First tower crane coming soon for PWC

Excavation of the PWC pit—which started back in 2020—finished earlier this year, and the concrete base for the first of three tower cranes that will be installed to facilitate construction of the underground structure has now been poured.

The first crane is expected to go up within the next month, and will be used to lift materials and equipment in and out of the pit. Actual construction of the PWC is expected to start this fall, and will begin in the west.

Once the second tower crane is installed in the middle of the site, the ramp that’s currently being used to access the pit will be removed, and workers will instead have to access it through scaffold stairs, which have already been installed.

The PWC will be the new public entrance to the Hill, and will also serve as a connection hub for the rest of the parliamentary campus, including buildings south of Wellington Street.

The three-storey underground structure will offer up roughly 32,600 square metres of new space. Along with tunnel connections to precinct buildings and new meeting space for parliamentarians, the PWC will feature security screening for visitors, a café, a gift shop, and an expanded suite of visitors’ services on its first floor.

“You’ll have spaces like classrooms, a multimedia theatre, exhibition spaces,” explained the Library of Parliament’s Kali Prostebby. “The Parliament Welcome Centre will become a destination in and of itself, including for people who don’t actually go to Centre Block,” if guided tours are full, for example, or if public access is suspended during a state visit.

With expanded security capacity and more sights to see, Prostebby said the PWC is expected to roughly double the number of annual visitors to Parliament, from an average of 350,000 to 700,000 people per year.

Detailed design plans for inside the space—including the kinds of materials that will be used—are still being finalized.

As part of the broad concept that has been set out, visitors will move around the rounded base of the Peace Tower—the otherwise unremarkable rock of which will be covered in some type of stone-cladding—to enter Centre Block through either its west or east courtyards, and will be able to peek up at the looming tower through skylights as they go.

New Senate viewing option to be offered

The Nov. 14 tour featured slightly less scaffolding than visits past, most notably in the Senate Chamber where scaffolding previously erected to allow workers to access and investigate the state of the ceiling has been dismantled.

Currently stripped back to bare bricks, when it reopens, the Senate Chamber will have a few new features, including broadcast capability—something it didn’t have pre-closure—and a new glass-enclosed viewing deck that will be accessible from Centre Block’s fourth floor.

“We have numerous visitors from school groups to visiting dignitaries,” said the Senate’s Louise Cowley. The “glazed enclosure” will offer an opportunity to “look into the Chamber, hear about the proceedings, but not actually interrupt Parliament.”

“This was something that we saw in various Parliaments around the world and decided to add here as well,” said Cowley.

Previously, the Senate Chamber’s interpretation booth sat in the space where the enclosure will be built, but that’s been pulled out in light of plans to create a centralized simultaneous interpretation space on Parliament Hill.

The Hill Times confirmed there are currently no plans for a similar enclosure in the House of Commons Chamber where interpretation booths pre-closure were situated at ground level.

As reported back in February, plans for the Red Chamber also include installation of new stained glass clerestory windows.

Scaffolding will have to return to the Senate Chamber down the road for the actual restoration of its gilded ceiling on site. Mohajer explained that it was taken down in the interim as it was determined to be cheaper to take down and put back up than to keep paying rental costs.

Restoration of the House Chamber’s painted linen ceiling is a different undertaking altogether.

Brothers David and John Legris, second-generation painting conservators with Legris Conservation, talked reporters through the work that’s gone into restoring the Lower Chamber’s ceiling, which has been removed and is currently being stored offsite in advance of conservation.

Removal of its painted linen panels happened in the midst of demolition of hazardous material abatement work inside the building, and presented hazards of its own. The ceiling itself is made up of multiple layers, with painted canvas stretched over wood straps mounted onto plaster, and with a layer of horsehair to help with sound absorption in between.

“It was about six-foot sections [that] we lowered to the table, and we could actually clean the back of the canvas [before rolling it up for removal], which had some kind of gross things falling from the ceiling,” shared David Legris. “There was insect droppings, mice droppings, things like that—a lot of debris coming from the horse hair and upper plaster.”

Restoration will also involve fixing the many water stains that mark the painted canvas.

While the heritage aspects of the old ceiling won’t be altered, some new materials will be used as part of restoration work, namely replacing the old horse hair with “modern materials that follow fire safety” standards.

“The next step is doing that, and then eventually reinstallation,” said David Legris.

What’s old is new

Water damage is something that’s affected spaces throughout Centre Block, including the House Speaker’s dining room—a new stop on the tour.

One of roughly 50 high-heritage spaces throughout Centre Block—and one of a suite of rooms designated for the Speaker’s use, which is usually out-of-bounds to all but invited guests—the space offered a good example of the depth of heritage restoration being done in Centre Block alongside modernization.

Prior to renovations, the room featured wood and cream fabric panels along its walls, and a white ceiling with a decorative border.

But it didn’t always look that way. Originally, the room’s walls featured a painted design—a mixture of dark green, browns, and gold—and its ceiling had a gilded gold finish.

As PSPC heritage management officer Kate Westbury explained, “100 years worth of water damage that occurred due to a flat roof condition that’s above” prompted renovations in the 1960s that saw the wall paneling installed and the ceiling painted white.

Through renovations, the room’s original details will be restored, including its gilded gold ceiling and stencil patterns that were previously painted over on its curving vaulted walls and have since been uncovered.

Speaking in “defence of those who came before us,” Westbury noted that this is the first time since its construction that Centre Block has been fully cleared out for renovations, and previously, “small piecemeal changes had to occur because they needed to be done” during summer recesses or other sitting breaks.

“We’re now given the luxury of being able to step back and make coherent design choices and decisions without having those types of pressures or constraints,” she said.

Similar decisions to restore original details have been made throughout the building, and the list includes the restoration of natural light to certain spaces, including the second-floor Senate and House foyers. Both foyers feature laylight glass ceilings, which have been lit artificially since being covered over as a result of roof leaks decades ago.

Fill in the blanks?

Masonry restoration is another huge component of the Centre Block project for both the building’s stone walls and its decorative stonework.

As part of the Nov. 14 tour, reporters were introduced to Danny Barber, a stone carver and sculptor with PSPC’s decorative arts team. He showcased a buffalo he spent the summer carefully carving, which will replace one from Centre Block’s west wall that was too damaged for re-use after more than 100 years of Ottawa’s freeze-thaw cycles, and wind and water erosion.

Barber showcased the different tools he used in sculpting the creature from a single block, ranging from “traditional calipers” to chisels, mallets, and other hand tools, as well as modern pneumatic tools.

“I’m very proud to have worked on this stone,” he said. “This isn’t the sort of thing that we get on our workbenches very often. We were born 100 years too late for that.”

Almost 200 blank stone blocks were left throughout Centre Block prior to renovations as part of the original architects’ desire to have the building be a living space upon which future generations could leave their mark.

Many of those blanks sit high on the walls of the House of Commons Chamber, and in turn, the current renovation project offers a unique opportunity to access and carve those stones.

PSPC has confirmed plans to carve up those blanks—with those in the House Chamber being eyed, in particular—but just how many will be carved and what the designs will feature is still to be determined.

Though a number has previously been floated, Mohajer said one idea currently on the table is to carve all 188 remaining blanks in Centre Block and instead leave the PWC as an area that can be added to by future generations.

The Hill Times

LICENSING

LICENSING PODCAST

PODCAST ALERTS

ALERTS