‘No sugarcoating the fact that changes are needed’: watchdog calls on feds to act now to fix procurement

Federal Procurement Ombud Alexander Jeglic says he is “absolutely frustrated” with the slow progress on fixing persistent issues plaguing federal procurement.

Jeglic released his annual report for 2023-24, titled Time for Action, on Oct. 21. The report underscores the urgent need for efforts to address long-standing procurement issues amid growing scrutiny from parliamentarians and Canadian taxpayers.

“There is no sugarcoating the fact that changes are needed,” Jeglic wrote in his report. “It is time to start to address these issues directly to make sure they do not impact our future the way they have impacted our past.”

“Am I frustrated that more has not been done to this date in terms of foundational changes? Absolutely,” said Jeglic in an Oct. 23 interview with The Hill Times.

“If you go back as far as 10 years, many of the issues we were trying to raise are still relevant today, [they] have not been successfully addressed.”

At the same time, Jeglic said “I’m also energized by what I’m seeing,” adding that there is a growing awareness around the importance of a transparent and efficient federal procurement system, particularly after revelations from the ArriveCan and McKinsey investigations.

“That’s why I believe the theme for the annual report is so important. We must not lose this energy or momentum, and ensure that key players remain focused on this issue,” he said.

Creating chief procurement officer role could help

Jeglic’s report reiterated his office’s push to create a chief procurement officer (CPO) role to address persistent issues within the system. The report noted that a CPO could focus on long-standing gaps in policy creation and implementation, and the lack of professionalization within the procurement sphere.

“There is no mechanism currently in the system to contemplate good performance in solicitation processes, and equally so, there’s no process by which to take into consideration poor performance,” Jeglic said. He said that this is why the government used such restrictive criteria to prevent poor performers from participating, and that they might have a specific entity they want to include—or exclude—from the process.

Jeglic added that his office has not done an overall review to provide a complete picture of the characteristics of firms that have been favoured in past government contracts.

Creating the CPO faces some obstacles with a lack of consensus on the role, including from people in the system who may “have to give up their piece of the pie to this global CPO position,” he said.

“The issue, really, is there’s huge accountability within federal procurement, and there’s multiple departments implicated, but ultimate accountability is unclear, and the main thrust of the creation of the role is to have [someone at the] senior level who has ultimate responsibility for federal procurement,” Jeglic told The Hill Times.

Jeglic’s report recommends creating a government-wide Vendor Performance Management program which would track supplier performance across departments, and hold vendors accountable for poor contract performance while rewarding strong performers, according to the report. Such a program could prevent favouritism towards certain vendors, Jeglic argued.

Unfair treatment is a top issue: suppliers

Federal suppliers complained 73 times about evaluation criteria for contracts that were unfair, overly restrictive, or biased, pushing that category to the top of 10 procurement issues the Office of the Procurement Ombudsman (OPO) tracked in the last year. There were 32 reports of unfair or biased criteria, 22 reports of restrictive criteria, and 19 reports highlighting bias for or against individual suppliers, or classes of suppliers. In 66 cases, stakeholders cited challenges in federal procurement, describing the process as “too long and burdensome,” with vague or contradictory information and difficulties using procurement systems.

Payment issues were reported in 24 cases where those trying to get federal business believed evaluations were incorrectly conducted, or contracts were awarded to the wrong bidder in 44 cases. In 11 cases, departments were reported to have deviated from the terms and conditions of contracts.

Jeglic emphasized the barriers suppliers face due to the complexity of federal procurement, which he said limits competition. The second most common issue raised to his office this year was the complexity of the process, with overly restrictive evaluation criteria and complicated language in solicitations discouraging contractors.

“These are things that have significant impacts throughout the system. We’re losing people because the system is too complex,” Jeglic told The Hill Times.

Jeglic’s report also underscored the principles of fairness, openness, and transparency in public procurement. He warned that favouritism can manifest through overly restrictive selection criteria—an issue the ombud highlighted in the ArriveCan report—or deviating from prescribed evaluation methods to benefit specific suppliers.

Jeglic said the lack of proper documentation hampers accountability and public trust in how taxpayer dollars are being spent.

“Canadians expect easy access to complete, accurate, and timely procurement information,” he said, urging the government to take immediate action to ensure contract data is available to the public.

Jeglic mulling Indigenous procurement review

The procurement ombud has also proposed regulatory changes to widen its authority, including the ability to review complaints related to contracts awarded under the Procurement Strategy for Indigenous Businesses (PSIB) set-asides program.

“We are considering a review of Indigenous procurement, but in order to launch a review, we need to establish reasonable grounds, and the scope,” Jeglic told The Hill Times.

A Sept. 17 motion proposed by Conservative MP Garnett Genuis (Sherwood Park–Fort Saskatchewan, Alta.) at the House Government Operations and Estimates (OGGO) Committee, which is studying Indigenous procurement, asks Jeglic to study it, too.

Jeglic said he can "anticipate" doing a study once his office receives a formal request from OGGO, and noted he has been made aware that it is likely forthcoming. Jeglic did not elaborate on the details of what an Indigenous procurement review would look like, saying it would be "premature" to discuss.

Contracts set aside pursuant to the PSIB are not subject to trade agreements, and therefore are not subject to the jurisdiction of either OPO, or the Canadian International Trade Tribunal. This means neither group has the authority to investigate complaints from unsuccessful Indigenous bidders or suppliers, which Jeglic said creates a fairness issue.

Jeglic also noted that some Indigenous-owned businesses have said they would welcome his office having jurisdiction to investigate these types of complaints. He said others want the recourse mechanism to be Indigenous-led, a position with which he said he does not disagree.

“More than 25 years have passed, and no formal mechanism has been established to provide Indigenous suppliers with a recourse mechanism—other than the courts—with respect to contracts awarded under the procurement strategy for Indigenous business set-aside,” he said.

Jeglic said other actors have responsibility in this area, such as Indigenous Services Canada, which must conduct an audit of the eligibility of Indigenous suppliers who are bidding for contracts, and have responsibility for the integrity of the Indigenous Business Directory. He noted there have been multiple instances over the years where issues were brought to OPO’s attention, but the ombud could not take formal action because they fell outside his legal mandate.

The federal government has had a procurement strategy for Indigenous businesses since 1996 to boost participation. It was revamped in 2021, and became the PSIB with a mandate requiring at least five per cent of contract value to be allocated to Indigenous firms. In 2018, more than $170-million in contracts were awarded to Indigenous companies under PSIB, which represents only one per cent of the total value of contracts awarded by the federal government that year. The value of government contracts awarded under the program reportedly rose to $862-million in the 2022-23 fiscal year.

According to government records, from 2022 to 2023 the government awarded businesses $33.5-billion in contracts, while 6.27 per cent—amounting to $1.6-billion—were awarded to Indigenous businesses.

Other regulatory changes Jeglic asked for are the power to compel—rather than request—federal departments to provide the necessary documentation requested to conduct reviews and investigations, and the authority to recommend compensation to suppliers exceeding 10 per cent of a contract's value.

OPO asking for more funding

Jeglic said his office needs more funding than the currently allocated budget of $4.1-million to support its growing workload. He said the office's budget has remained static for 15 years since its creation in 2008.

For the 2025-26 fiscal year, the OPO has asked the government for an additional $1-million, followed by $3.4-million for 2026-27, and approximately $4.7 million for 2028 and beyond. The OPO also receives one-off funding when a minister or parliamentary committee tasks it with doing a specific procurement review, but this doesn’t allow the office to hire full-time staff, according to Jeglic. Instead, the office often ends up needing to bring in temporary staff who may lack the tailored experience needed for the job, so the experience needs to be built up on the job.

“On paper, it might look like the problem is being addressed. It's really not. It's just exacerbating the problem,” he said.

This also means that the office is pushed to hire consultants or contractors due to lack of funding hindering the OPO from hiring full-time staff. The federal government's use of consultants and outsourcing government work has been highly scrutinized during the unfolding of the ArriveCan scandal.

“The irony was not lost on us,” said Jeglic, whose review into ArriveCan unveiled the deep-rooted issues in Canada’s procurement system.

“We refuse to do it because we just did not want to hire external consultants to review external consultants. We use internal government resources, but we funded them to our office on a short basis, consistent with the timing of the review,” he explained.

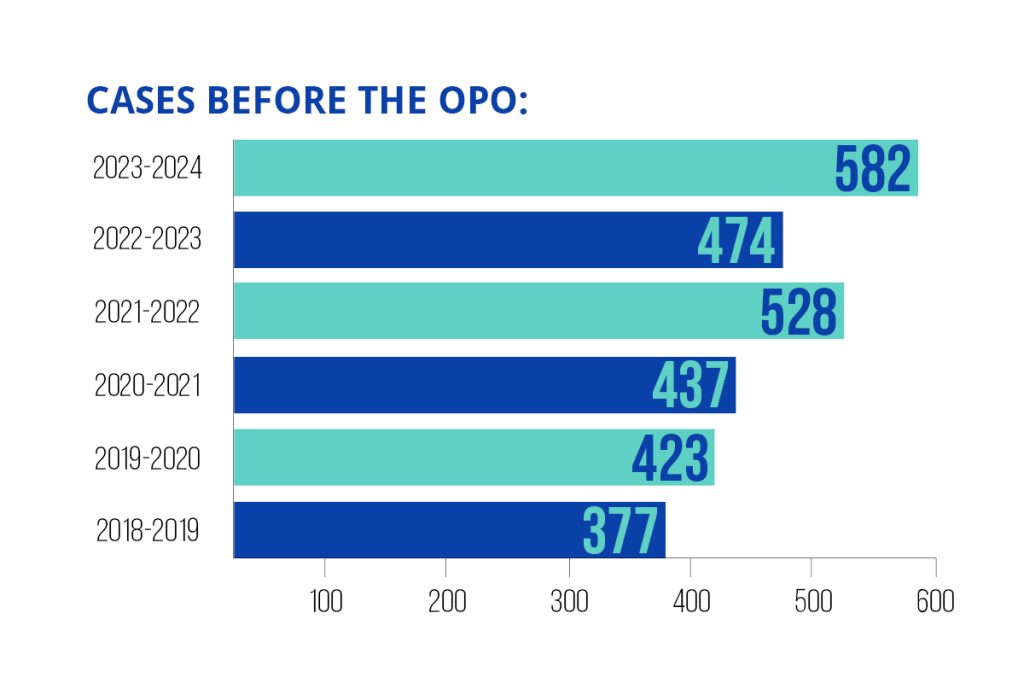

This fiscal year, the office had 582 procurement-related cases tied to reported issues, compared to 474 the previous year. It has also received 62 written complaints, and launched five reviews of formal complaints from Canadian suppliers related to the awarding of federal contracts. The office also completed five practice reviews, including three planned reviews and two ad-hoc reviews related to the ArriveCan application, and contracts awarded to McKinsey & Company.

ikoca@hilltimes.com

The Hill Times

Correction: This article was updated on Oct. 25, 2024, to clarify Procurement Ombudsman Alexander Jeglic said he does not disagree with the perspective that a recourse mechanism to investigate complaints related to PSIB should be Indigenous-led.

LICENSING

LICENSING PODCAST

PODCAST ALERTS

ALERTS