Is Canada’s military procurement system broken? Some defence experts say it is, others say it works as designed

Canada’s defence procurement woes continue as the cost to build Navy supply ships jumps by nearly $1-billion, spotlighting the delays, cost overruns, and bureaucratic red tape inherent in the system. Some defence experts say the system is “broken,” while others argue it works as designed.

High-profile projects like the procurement of F-35 fighter jets and warships have become synonymous with these issues, sparking debate on the system’s effectiveness. The latest example came on Aug. 2 when Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC) announced that the cost to build the Navy’s delayed supply ships has increased by nearly $1-billion. The Liberal government awarded Seaspan’s Vancouver Shipyards a contract in June 2020 to build HMCS Protecteur and HMCS Preserver for $2.44-billion. The contract’s price tag is now $3.3-billion, excluding design, support, and other related expenses, bringing the total expected cost to more than $5.2-billion. This is just the latest setback in a nearly two-decade effort to deliver joint support ships to the Navy.

Is the system broken?

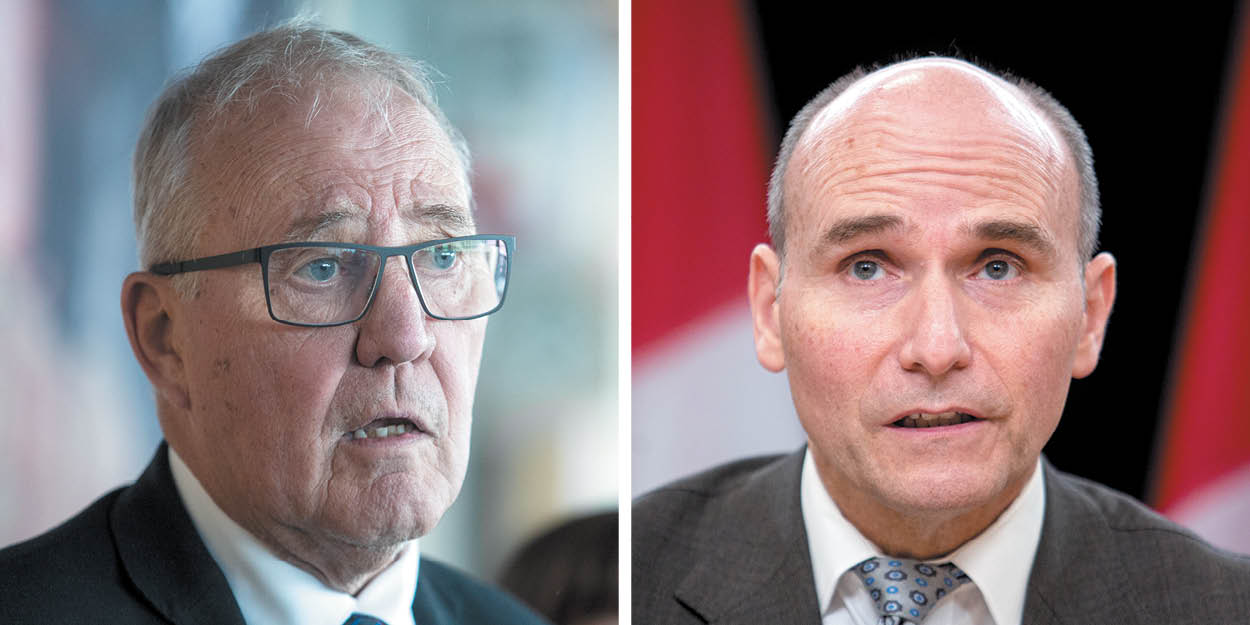

Mark Norman, a retired vice-admiral and a senior fellow at the Canadian Global Affairs Institute, argues both the military procurement system and the relationship with industry are “broken” and “need to be completely rebuilt from first principles.”

Norman—who spent more than three decades in the Canadian Navy and served as vice-chief of defence staff—managed numerous major procurement projects during his time in the Forces. He also came to public attention in 2017 when he was accused of releasing confidential information related to a $700-million procurement of naval supply ships. Charges were dropped in 2019, and Norman reached a confidential settlement with the federal government and he received an all-party apology from the House of Commons. Norman told The Hill Times that his views on procurement are “completely independent of that experience,” and it has not “clouded or influenced [his] thinking” on the matter.

Richard Shimooka defence procurement expert and senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, said that the current system is “just not delivering,” which leads to rapidly aging equipment and a loss of capabilities.

“If you look at the Canadian Armed Forces, that requires immediate replacement of several very essential systems, it clearly is [broken]. It is not delivering” said Shimooka. “We have an Armed Forces that whose equipment is ageing rapidly, some rusted out into nothing, so that we don’t even have those capabilities anymore.”

Procurement runs on “a consensus model,” which he said slows things down.

“If you are from one of the many departments that are involved [in the procurement process] you have the ability to veto or slow up the process by raising your objections,” he said.

“The process is designed not to be effective and not to be fast, unless there is, real political push at the top to get things going.”

For example, Shimooka pointed to Defence Minister Bill Blair’s (Scarborough Southwest, Ont.) comments in May that it’s hard to convince cabinet and Canadians that meeting the NATO two-per-cent of GDP spending target “was a worthy goal.”

Philippe Lagassé, an associate professor at the Norman Paterson School of International Affairs at Carleton University, argued the system works as successive governments have designed it—heavy on process, oversight, and caution.

Federal ministers are ultimately responsible for the state of Canadian defence procurement and “if they wanted a different system, they could get one,” argued Lagassé. “But they’d need to be willing to push for it, overcome bureaucratic resistance, and accept a higher level of risk for greater rewards. Until they’re willing to do so, we’ll be stuck with the system that we have.”

“It’s not broken,” said Dave Perry, supporting Lagassé’s take that the system is “delivering as it has been built to.” Perry said that the bureaucracy creates bottlenecks for senior officials involved in the procurement process due to complex procedures that only permit higher-level public servants—like associate deputy ministers and deputy ministers—to call the shots.

Perry said the government and the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) must make clear which procurement files are most important. The overall lack of capacity, including personnel, helps create a system that fails to deliver the desired outcomes, he said.

“If the prime minister doesn’t seem very concerned by how well all of this is going, then it shouldn’t surprise anybody that the bureaucracy is responding in a way that suggests a lot of other things in government are far more important than this,” said Perry.

What are the challenges?

Experts agree that the complexity of defence projects is the main challenge, noting that Canada’s military procurement system has been inherently complex by design. The intricate web of regulations, lengthy approval processes, and politics all slow down procurement timelines, they say.

The skills and knowledge deficit in procurement is exacerbated by political decisions, budget cuts, and staffing shortages, argued Ian Mack, a former rear admiral and director general in the Department of National Defence. Mack—who was involved in the creation of the National Shipbuilding Strategy from its inception in 2008 until 2017—also pointed out that realistic cost estimates for weapons platforms only come after design and testing, but the government prematurely announces schedules and budgets.

Lagassé said it’s difficult to anticipate price if the estimates are made before the project has started, or discussions with industry on requirements are complete, and reveals the problem is “optimistic costing.”

“The budget overruns reflect the fact that the initial funding isn’t realistic or tied to anything tangible,” explained Lagassé.

“Individual projects can face budgetary shortfalls that involve trades-offs and compromises,” he said. “Mostly, though, it’s the challenge of trying to acquire the right capability, for the best price.”

Experts also cited Canada’s Industrial and Technological Benefits Policy as an additional layer challenging defence procurement. It requires companies awarded defence contracts to invest in Canadian industry, which can complicate procurement processes and extend timelines.

Issues with procurement affect CAF’s operational readiness, say experts

Experts agree that current geopolitical tensions—including Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, escalating tensions between China, and increasing regional instability in the Middle East—make fixing procurement issues essential to mitigate Canada’s risk. More delays and inefficiencies in procurements of military capabilities could compromise the operational readiness of the Armed Forces, they say.

“If we don’t improve the process, the CAF will be at a disadvantage when sent into harm’s way,” said Craig Stone, an emeritus associate professor of defence studies at the Canadian Forces College.

That sentiment is echoed by others who emphasize the urgent need for modernization in procurement practices.

“Canada needs to adapt its procurement system from a relatively peaceful era with gradually evolving technological change to a wartime footing with rapidly changing technologies,” said Lagassé. “If we don’t, we’ll lose relevance and put CAF lives at higher risk than is necessary.”

Mack said Canada risks being “relegated to the sidelines” and relying on other countries.

“If we cannot equip the Armed Forces with state-of-the-art capabilities when they need them, they will find themselves either in harm’s way (such as an immediate human disaster),” Mack said by email.

“This is critical,” agreed Norman. He added that getting military procurement on track is an essential step towards Canada achieving NATO spending targets and “to fundamentally rebuild the Armed Forces to meet the rapidly degrading global security environment.”

‘Politics influence the delivery of projects‘

The government’s 2017 defence white paper, Strong, Secure, Engaged, found that 70 per cent of all defence procurement projects were not delivered on time. The April 8 update to the government’s defence policy, Our North, Strong and Free, did not provide a similar analysis. The Department of National Defence did not respond to The Hill Times‘ request for one by deadline.

Stone argued that political and economic considerations slow down the procurement process and increase risk aversion, which hinders the successful delivery of major defence projects. He also emphasized that billions of dollars are spent unnoticed because projects are completed on time and within budget, but big-ticket items make the news, because they reveal political interest, interference, or direction. Stone cited the F-35 procurement as one of those examples of a “real failure,” influenced by politics and the years-long back-and-forth in execution under both Conservative and Liberal federal governments.

The Liberal government signed a $19-billion deal last January to buy 88 F-35 jet fighters to replace the Air Force’s aging CF-18s, but efforts to buy the aircraft date back to 2006, when the Conservative government under prime minister Stephen Harper made the initial commitment. Harper’s plans to sign a $9-billion contract for 65 F-35s at the time were shelved in 2012 following criticism from the auditor general and the parliamentary budget officer over projected costs. In 2015, then-Liberal leader Justin Trudeau (Papineau, Que.) campaigned to cancel the F-35 acquisition and followed through on this promise. After exploring other options, the government launched a competitive bidding process, and Lockheed Martin, the manufacturer of the F-35, ultimately won. The first 16 jets are expected to be delivered in 2026.

Another military procurement affected by provincial and federal politics was the controversial procurement of Boeing’s P-8A Poseidon surveillance aircraft, noted Stone. In late 2023, Canada inked a $10.4-billion sole-source deal to buy at least 14 of the aircrafts from the United States, replacing its ageing fleet of CP-140 Auroras. The decision took months with Quebec-based Bombardier pushing Ottawa to consider its own alternative proposals before buying the American option.

Political direction and decision-making is “critical,” noted Stone. He explained that, during the Afghanistan mission, “when Canadian Armed Forces members were in harm’s way, decisions were made quickly” by using the Advance Contract Award Notice process, which shows that rapid procurement mechanisms exist. However, when CAF members are not in immediate danger, the government’s economic and social requirements take precedence, Stone said, which adds time to the procurement process.

The House Defence Committee, meanwhile, published a report on June 19 concluding its year-long review into Canada’s procurement process impact on the CAF. The report highlights how “the complexity” affects not only project delivery “on time and on budget, but also transparency and oversight regarding them.” Witnesses told the committee that processes are “too complicated, politicized, bureaucratic, and slow,” which they said limits the Armed Forces’ capabilities. One of the report’s 36 recommendations was for the government to “depoliticize procurement decisions.”

Norman echoed the report’s suggestion, saying “a more unbiased process for approvals and decision-making” is important.

“The politics of procurement is problematic,” said Norman, who noted “it’s understandable that when billions of dollars are involved, politics will be hard to avoid.”

Christian Leuprecht, a professor at the Royal Military College of Canada, said procurement ultimately hinges on political will. “Politicians love to blame it on expenditure frameworks, bureaucratic dysfunction, etc. But we live in a Westminster constitutional democracy that is premised on ministerial responsibility, so, it will only happen if there’s political will,” Leuprecht said in an email.

Canadian politicians are “exceptionally focused” on industrial and regional benefits of defence procurement, argued Leuprecht, because “that’s how you build consensus in cabinet, in caucus, and across party lines.” But he said the problem is these benefits are “often elusive, and impossible to measure” and they “massively drive up the cost of procurement projects, in many cases, doubling, tripling, or more the project.”

In a May 12 National Post article, former Liberal MP and retired lieutenant-general Andrew Leslie wrote Trudeau “is not serious about defence. Full stop. A large number of his cabinet members are not serious about defence. Full stop.”

Stone argued the layers of bureaucracy are another major issue hindering the successful delivery of major military procurements because it means meeting multiple ministerial mandates with differing priorities. Project requirements—including operational needs, economic benefits, socio-economic factors, trade requirements, and competition—are just layers adding onto the many challenges involved in any major equipment purchases, he explained.

Norman expressed a similar view and suggested that the military procurement should be handled by a single and impartial authority—like a special operating agency or a Crown corporation—instead of being overseen by multiple departments with their own agendas and biases.

Stone highlighted the lack of expertise and the shortage of personnel among military, public servants, and industry as significant challenges. An internal DND memo from 2023 highlighted a “critical shortage of procurement experts” and revealed that 30 per cent of roughly 4,200 military procurement positions were unfilled at the end of May 2022.

Norman said the CAF keeps equipment for too long and then faces “repeated and avoidable ‘crises’ to replace equipment which is obsolete or too costly to maintain.” Compounding that issue, both CAF and DND “take far too long” developing requirements for new capabilities and making those requirements “far too specific,” he said.

“This is partially a function of them only getting a chance to get a new ‘thing’ every 30 to 50 years, so they feel compelled to try and get as much as possible in that next purchase,” Norman explained. “Delays in finalizing requirements directly affect design, engineering, and costing which all subsequently contribute to additional compounding delays and cost escalations.”

The Canadian Surface Combatant project will replace the Navy’s aging destroyers and frigates with 15 new warships. The first request for proposals was released back in 2016. Irving Shipbuilding Inc. was awarded the contract in 2019, and the first vessel is expected to be delivered in the early 2030s. National Defence estimates the total cost is between $56-billion and $60-billion, but the parliamentary budget officer puts the cost closer to $84-billion.

Stone explained that cost overruns for the Canadian Surface Combatant are due to changes in the initial equipment, with the Navy amending and establishing requirements that differ from the original design construction and first article testing. Stone linked this issue to a lack of expertise and trust between the government and industry.

How much does Canada spend on defence procurement?

The government pledged in the April policy update to invest $8.1-billion over the next five years and $73-billion over the next 20 years in national defence. A significant amount of the 20-year investment will be for procurement, with $9-billion allocated to sustain military equipment. Another $9.5-billion over 20 years is for new artillery ammunition production capacity in Canada, and investing in a strategic supply of ammunition.

How is Canada doing in comparison to its allies?

Experts agree that other countries are also dealing with military procurement issues, but Canada is lagging behind its allies.

“All of our allies have examples of major procurements being late, over budget, or not meeting operational requirements,” said Stone. “There is no silver bullet solution to defence procurement.”

Canada “seems to be worse than most,” according to Norman. He said those with strong procurement processes have tighter authorities and approvals, as well as clear lines of accountability. These countries also have better relationships with industry, or they purchase directly from preferred suppliers, he said.

Shimooka said Canada struggles to deliver off-the-shelf systems—ready-to-use weaponry or systems that need no or little modification—which often mirrors the time it takes countries like the United States to develop new systems from scratch and get into service.

“We’re really at the low end of this. We have one of the worst procurement systems in the West,” he said.

The Hill Times

LICENSING

LICENSING PODCAST

PODCAST ALERTS

ALERTS