Predicting Poilievre’s foreign policy plans

OTTAWA—Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre has made it clear he will not pivot if he becomes prime minister. Good. Now we know his domestic policy will focus on things like “axe the tax,” and something to do with combatting “woke” issues. What about his foreign policy?

There are naturally the “globalists” he wants to confront by never going to the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. He will nonetheless go to Brussels, Belgium, where NATO is located. Poilievre has promised to “work towards” spending two per cent of our GDP to feed NATO’s war addictions, but not if it gives Ukraine a fighting chance with Russia. He likes Russia, maybe?

We could glean more from Poilievre’s campaign speeches and keep making snarky observations about plans for the World Health Organization, for example, but it’s not helpful. His bombast helps hold his lead in the polls, but it’s not for policy-making. After all, what does the word “woke” mean anyway? And how do you turn it into a viable policy? Ditto for “globalists.” Who are they? Surely, it’s not yet another form of anti-Semitism as some have suggested.

Governments don’t base their foreign policies on dog whistles or conspiracy theories, but on pragmatism, which entails exploiting domestic opportunity, advancing vital national interests, and implementing political ideology. This framework is a saner approach through which to examine Poilievre’s potential plans.

For domestic opportunity, Poilievre as prime minister would be pressured to expend his political capital to pay back his initial base of supporters, like the evangelicals and white nationalists. This he can do quite easily. Like former prime minister Stephen Harper, he could tie development aid to anti-abortion policies, pledge to move the Canadian embassy in Israel from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, and throw in a few bigoted policy ideas to bait and blame asylum seekers.

For vital interests, he has two big fan favourites: foreign interference and border security. No one is about to invade our borders, but we have the Arctic. Like Harper, Poilievre will try to defend the Arctic. With the new Liberal defence policy also emphasizing the Arctic, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has given enough fuel for Poilievre to ramp up his rhetoric on the Arctic. Foreign interference, on the other hand, might get tricky. Poilievre is hard on China but soft on India. He hasn’t criticized India’s meddling in Canada’s domestic affairs. Instead, he blames Trudeau for souring affairs between the two countries.

The most vital foreign policy interest for any prime minister, however, is international trade. It’s the core of the economy. With his fixations on rules-based order and “friend-shoring,” Trudeau has arguably failed on the trade file. Poilievre is not bound by Trudeau’s neoliberal obsessions. He can sell Canadian commodities to the highest bidder and, using the Harper playbook once again, make trade the centrepiece of his foreign policy program.

Except, that is, for his inner circle. It is chalk full of parochial diehards, lobbyists, and think-tank operatives. Their influence could turn his trade agenda into a set of hit-and-miss dogmatic transactions. There is also the spectre of Harper himself, who may use his outfit, the International Democratic Union, to pull Poilievre towards the policy fraternity of neocon authoritarian parties in places like Holland, Hungry, Austria, Chile, and the Czech Republic.

Poilievre’s challenge will be avoiding blimpish ideologies and instead relying on policy realism. Ideologies aren’t bad, per se. They can provide a setting in which policies can be placed to make unified sense. The downside is that ideologies are rigid, and if they are not aligned with the zeitgeist, they backfire: ask Liz Truss, the short-lived British prime minister. She now has a new gig, incidentally, as an honourary advisor to Harper.

This theoretical math may mean very little. It’s just guess work. By the time Poilievre takes charge, Trudeau would have dissolved any semblance of Canadian foreign policy independence, anyway. We will be unambiguously meshed to the geopolitical ambitions of the United States. Poilievre may have no choice but obey the dictates of the next U.S. president.

If Donald Trump wins, we can expect a full court press of reactionary right-wing negations: no to Ukraine, no to NATO, but mostly no to China. China, it’s a sure bet, will become enemy No. 1. That fiits well with Poilievre. His foreign affairs critic, Michael Chong, is already on it. Chong eats and breathes China and, as the Conservative handbook of the 2021 election lays it out, the Conservatives aim to rough up the Chinese Communist Party, no less.

But if Joe Biden wins, then Poilievre may have to hold his breath. Presidents from the Democratic Party tend to use their second term to build a legacy of progressive achievements. Like former U.S. president Barack Obama in his second term, Biden might open up to Cuba, cut the nuclear deal with Iran, isolate Israel, and ease up on China. That could be a problem for Poilievre.

It need not be. After a near decade of the Trudeau Liberals, our clout in the world is next to negligible. We are mired in unending wars and imperialistic buffoonery. Poilievre could break this unproductive cycle. He could build our foreign policy on tact, soft diplomacy, negotiations, and dialogue. That won’t happen though. He is apt to label those kinds of things as too “woke.”

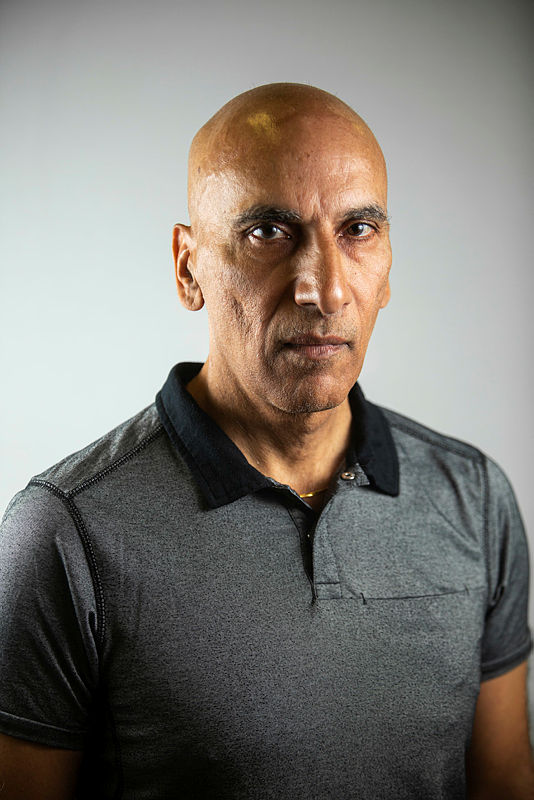

Bhagwant Sandhu is a retired director general from the federal public service. He also held executive positions with the governments of Ontario and British Columbia.

The Hill Times

LICENSING

LICENSING PODCAST

PODCAST ALERTS

ALERTS