It’s difficult to ‘follow the money’: former MPs, bureaucrats, and PBOs say budget and estimates process makes it tough for Parliament to hold government spending to account

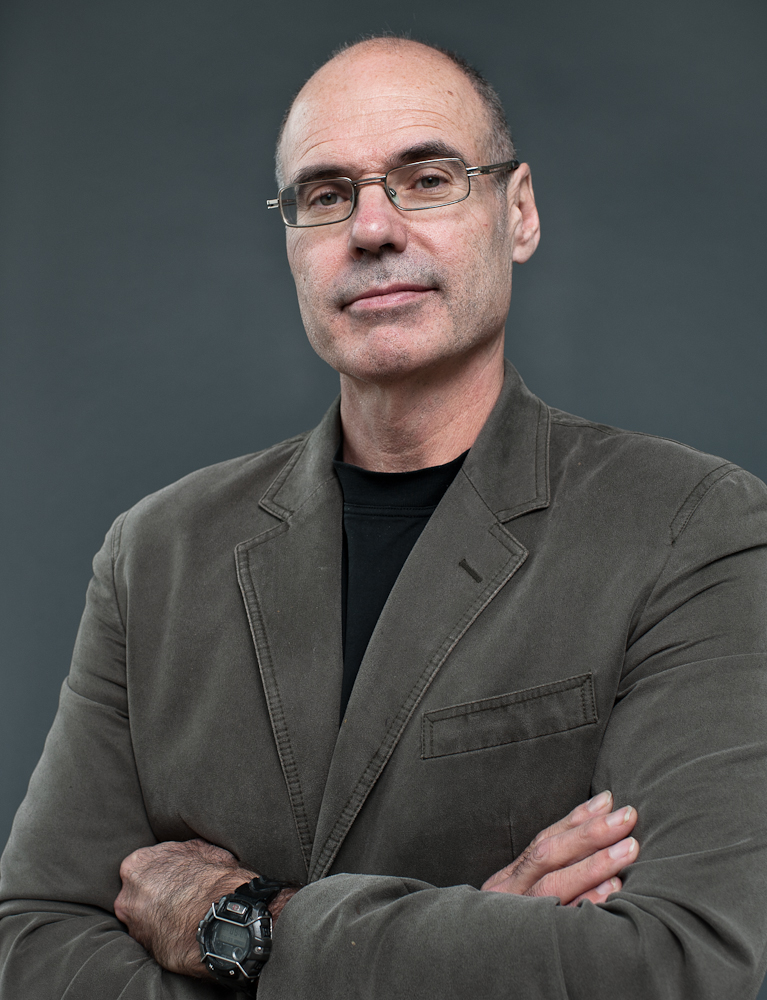

When former parliamentary budget officer Kevin Page thinks about what’s wrong with the process by which MPs scrutinize the government’s spending—a system that has been described by the current PBO as “unnecessarily complex”—he thinks about how his father might have looked at government finances if he had ever become an MP.

“I grew up in Thunder Bay. My mom and dad didn’t finish high school. Dad was a machinist,” Page told The Hill Times. “They’re long gone. But they should be able to read the budget—you know, in terms of basic spending lines, revenue lines, these are the new measures, this is how it adds up—and as long as they lived, I’m sure they wouldn’t be able to do it.”

Page said he believes the current system of budgets and estimates is too opaque, and happens on a flawed timeline, leaving MPs and the general public disconnected from the process and unable to closely follow how billions of dollars in public money is being spent.

The government just tabled its $449.2-billion in spending estimates for 2024-2025. MPs will vote on $191.6-billion, while $257.6-billion are statutory authorities, meaning the government already has Parliament’s permission to spend it.

Page, who served as Canada’s first parliamentary budget officer from 2008-2013, has been a longstanding advocate of reforming the system that Parliamentarians use to scrutinize and approve government spending—one of the most fundamental roles they perform as the elected representatives of Canadians.

“I was always kind of thinking about, if my dad became an MP, didn’t finish high school, I would want it to be [that] he can be a good MP—he should be able to read these documents, and actually have tough questions for people,” Page said.

Page said the current system needs significant changes for that to be the case.

‘You’re flying blind’: former MP Bateman

As the government prepares to deliver its budget next month, The Hill Times spoke with current and former PBOs, former bureaucrats who worked for the Department of Finance and Treasury Board Secretariat, and current and former MPs for this three-part series about the problems with the current process, why they affect fiscal accountability, and how the system can be improved.

Page said problems with the system go back decades, and that Canada has never—in his view—had a highly effective system for how this information is provided to Parliamentarians and the public. Attempts at reform in recent years have been unsuccessful.

A central concern expressed by many of the sources consulted for this series was the timeline by which the budget and estimates are rolled out.

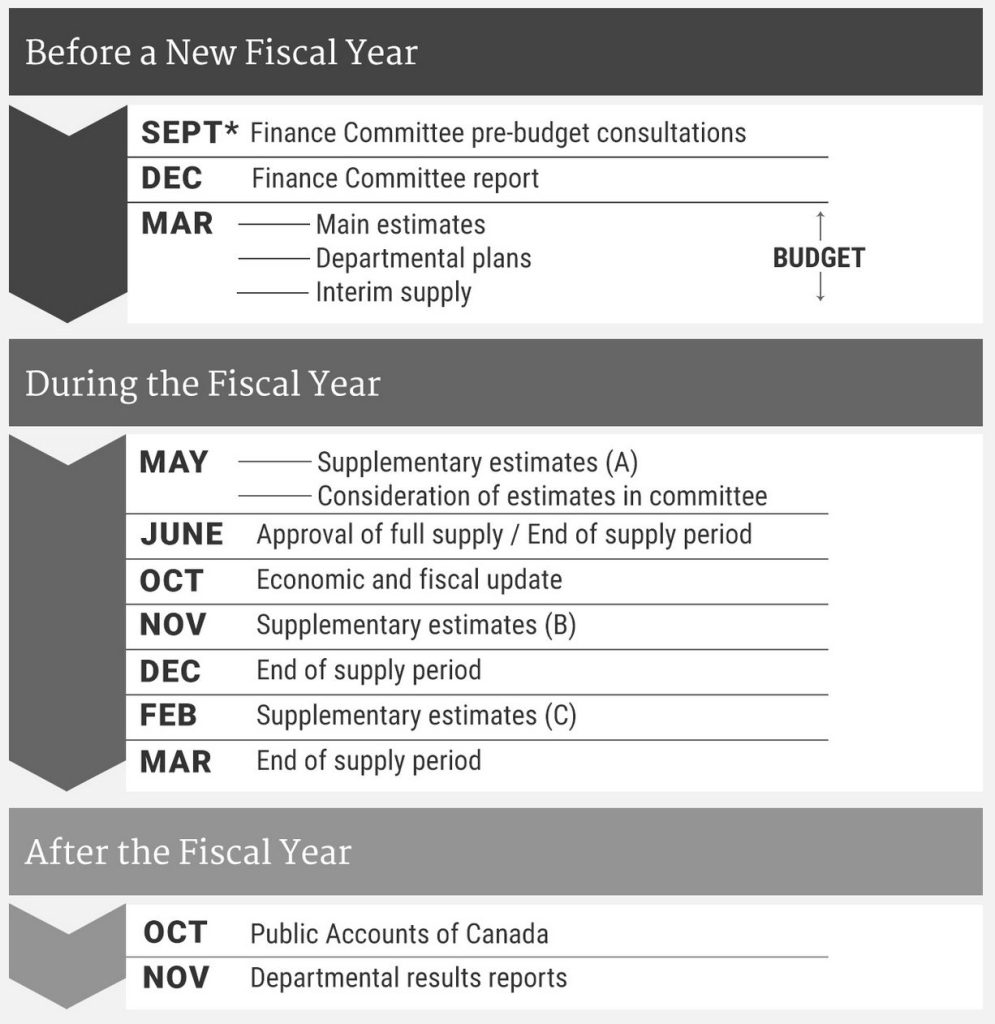

Under the current process, the budget is often released several weeks after the tabling in Parliament of the main estimates—which lay out initial spending plans for each federal department and agency for the year, and are typically followed by three supplementary estimates (sometimes fewer). The main estimates are generally prepared in the fall, and the Standing Orders require them to be tabled by March 1. However, there’s no fixed date for tabling the federal budget, which may be tabled weeks after the main estimates and sometimes (as will be the case this year) after the new fiscal year has begun on April 1.

This year’s federal budget is set to be tabled on April 16. The 2024-25 main estimates were tabled in the House on Feb. 29, and as such do not include any new spending that will be announced in the budget, which would instead be put to Parliament for approval through subsequent supplementary estimates.

Following the end of the fiscal year, the Public Accounts are tabled in the fall—typically October—detailing actual spending and revenues, as well as liabilities, assets, and net debt as of the end of that fiscal year (so, the Public Accounts detailing actual spending in 2023-24 can be expected in the fall of 2024).

In addition to concerns about the timeline, many sources consulted by The Hill Times described the documentation as highly opaque, and said the budgetary process led by Finance Canada and the estimates process by the Treasury Board Secretariat are not well integrated.

Parliamentary Budget Officer Yves Giroux told The Hill Times that the current process is “unnecessarily complex.”

“What makes it difficult for Parliamentarians is the misalignment between the budget and the estimates process,” said Giroux.

He emphasized that, in his view, it is not that the current system “doesn’t work” or that there’s “money unaccounted for”—as “that could lead people to believe there’s something inappropriate being done”—but rather that “it’s very difficult for Parliamentarians and Canadians to figure out how the mains the supps and the budget work together.” As a result, Giroux said it’s difficult for MPs and Senators to “follow the money” on specific initiatives, and to bring the level of scrutiny that Parliament is meant to deliver in its role of ensuring the nation’s finances are used wisely.

He said, in his view, the central problem is that the main estimates are released before the budget—because this creates a situation where the mains do not reflect new programs that will be announced a few weeks later.

“It makes Parliamentarians’ jobs very difficult to hold the government to account, scrutinize government requests for funding and spending, given that they can’t see budget initiatives in the mains, and they have to put together multiple pieces of legislation—mains and two or three supplementary estimates—to have a complete picture of government expenditures,” he said.

For an opposition MP, or a government backbencher, Giroux said this means that when reviewing the main estimates, they are working with “a very inaccurate picture.”

“Anything that the government will touch in the budget, they can’t really reveal their hand in the mains because that would be disclosing information that they haven’t decided on yet, or that’s not ready to be disclosed publicly,” said Giroux.

Former Conservative MP Joyce Bateman, who represented the riding of Winnipeg South Centre, Man., from 2011-2015, told The Hill Times that she also sees this timeline as a problem.

“You’re flying blind,” said Bateman, a chartered accountant who had stints on both the House Public Accounts Committee and the Finance Committee during her time as an MP.

“You look at this year—I mean, the main estimates won’t include any of the spending promises of the April 16 budget,” she said. “And it’s doable to follow the money, but it sure requires a mammoth reconciliation effort, and a lot of hard work. And not everybody has the tools or the skills or the interest to do that.”

When the main spending estimates are released before the budget, Giroux said this creates a second problem for MPs at the time the budget is released. At that juncture, they find themselves looking at initiatives announced in the budget without sometimes knowing which departments will receive the funding for those initiatives—especially in cases when funding for an initiative is to be spread across multiple departments.

In that case, MPs must wait for the next round of supplementary spending estimates released later in the year. However, by that time, departments may have already begun to spend on the initiative—in the anticipation that supply would be approved in the supplementary estimates—making it difficult for MPs to exercise much discretion on how public money is used. In such a situation, if the spending is not approved by Parliament, the department would then likely try to move funds around within the department to make up for the funding it would not receive, said Giroux.

“So it makes it so that individual MPs and Senators have very, very little influence on government spending—even committees have very little influence,” he said.

‘A binder the size of a Manhattan phone book’: former MP Martin

In addition to the timeline by which the process happens, Page said the format in which much of the information is presented is also a problem.

Former NDP MP Pat Martin, who represented the riding of Winnipeg Centre, Man., from 1997-2015, led an attempt to reform the process during his time as chair of the House Government Operations and Estimates Committee from 2011-2013, and has been a long-standing critic of the process.

In an email to The Hill Times, he said parliamentary oversight of public funds is a “fundamental cornerstone of our democracy” and he continues to care deeply about “the importance of scrutiny and oversight as the primary task of Parliament.”

Martin pointed to a speech he gave in February 2013 at a meeting of Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development parliamentary budget officers held in Ottawa. In his remarks, Martin highlighted some of his longstanding concerns with the system.

“I think Canadians would be horrified to learn that hundreds of billions of dollars in proposed spending is approved by Members of Parliament each year with virtually no scrutiny or oversight or due diligence, and how little time and attention is given to the main estimates in the financial cycle,” said Martin in his speech.

He said the spending estimates process is a “classic example” of how a “data dump” can be a means to obfuscate rather than enlighten, adding that “too much information in an inaccessible format is as bad as getting no information at all.”

“The estimates arrive in a binder the size of a Manhattan phone book and in a format that is almost impossible to understand by anyone other than a forensic accountant,” said Martin, who is a carpenter by trade. “MPs haven’t got a prayer of making sense of this material. I’m the chair of the committee and a six-term veteran, and I can barely figure it out.”

Martin added that, in his experience, the time spent by standing committees to review the spending of their relevant departments was much too brief—with usually only a single hour spent questioning the minister.

“It’s a matter of debate whether this appalling system of approving the estimates has evolved this way by design or simply by neglect,” said Martin, “but the net result is that the government gets a free pass and doesn’t have to explain or justify anything to anybody, much less the pesky representatives of the people.”

Expenditures not always well-linked to results: Samson

Several former bureaucrats who worked across multiple federal departments said the current system has problems.

Don Drummond, who spent more than two decades as an economist at Finance Canada and is now a fellow-in-residence at the C.D. Howe Institute, said the current timeline can lead to a mismatch in assumptions between the annual budget and the main estimates.

“As an MP, you want the main estimates and the budget to be as equivalent as possible,” said Drummond. “You don’t want to be going through the main estimates and then have some other event come up and change things.”

Drummond said the longer the gap between the mains and the budget, the greater the chance that events—either government announcements or other economic factors—will lead to these two documents being based on a different set of assumptions.

“And so the Parliamentarians have to kind of try to master the main estimates, and then all of a sudden they get something else coming at them that has new information,” he said.

Rachel Samson, an economist who worked at both Finance Canada and Treasury Board, said “challenges have existed for a long time” when the budget comes late and the main estimates come early.

However, she said, in her view, improving the way information is presented is an even more pressing issue.

“What seems to be more important is fixing the way the information is presented so that it is clearer, and there is more potential for scrutiny, because a lot of the incentives right now are to present information in an opaque way,” said Samson, who is now vice-president of research at the Institute for Research on Public Policy.

She said efforts to better tie expenditures to results in the estimates and departmental reports require further work.

“It’s high-level language. The specific numerical targets are infrequently reported or not necessarily linked to expenditures as well as they should be,” said Samson——though she added she is sympathetic to the challenges to achieving this that exist on the bureaucratic side based on her time in the public service.

Page also pointed to this issue of linking expenditures to results.

“They include spending that they don’t actually tie to specific initiatives in some of these tables now,” said Page.

He said he imagines better linking spending to outcomes would help to engage someone like his father—either as a member of the public, or if he was an MP—since representatives are meant to come from all backgrounds.

“They shouldn’t be voting on these votes that hide all kinds of things into an operating vote or capital vote or a transfer vote,” he said.

Instead, he said, as an example, for MPs from a coastal riding, “They should vote on icebreaking. They should vote on fisheries management. They should vote on these things because they’re relevant to people.”

“We can fix this system,” said Page. “It can be way better than it is now.”

This is part one in a three-part series on the budget and estimates cycle. Parts two and three will look at the role of MPs and why fiscal accountability is important to democracy, and how the system can be improved.

icampbell@hilltimes.com

The Hill Times

LICENSING

LICENSING PODCAST

PODCAST ALERTS

ALERTS