‘A lot of outstanding detail’ on pharmacare leaves program’s future riding on talks with provinces

Compromises made by both the Liberals and the NDP to achieve a pharmacare deal that’s light on details point to the relative weaknesses of both parties at this time, rather than either one having secured their preferred outcome in negotiations, says pollster Darrell Bricker.

“Neither one wanted to have an election. You’ve got [NDP Leader] Jagmeet Singh saying, ‘Please do anything that I can justify in order to be able to not have to go back on this agreement,’” said Bricker in an interview with The Hill Times. “And the Liberals are saying, ‘Well, yeah, we’ll give you what you need. But I know that you’re not going to force an election.’”

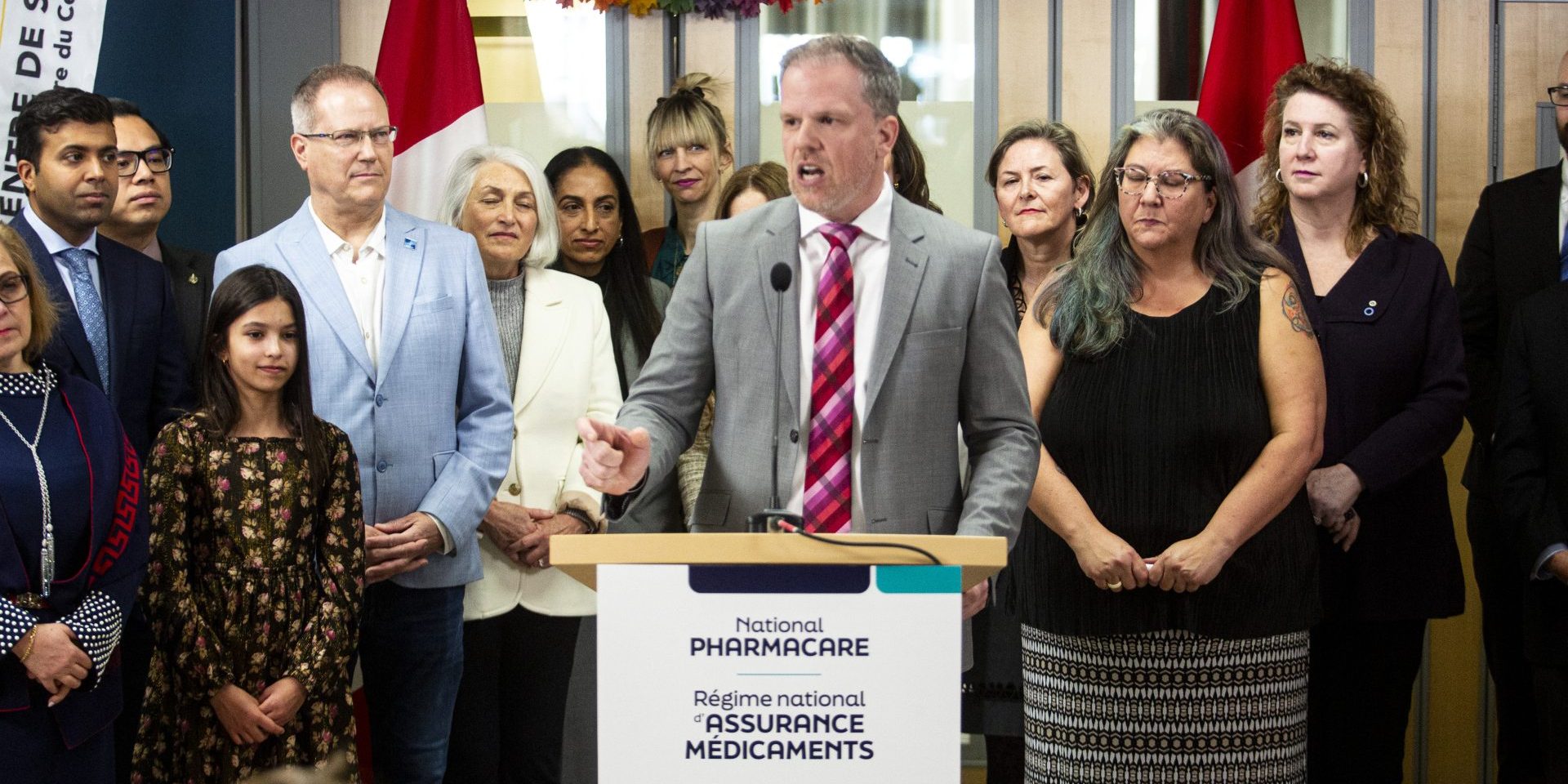

On Feb. 29, Health Minister Mark Holland (Ajax, Ont.) appeared at the Ottawa’s Centretown Community Health Centre, alongside NDP MP Don Davies (Vancouver Kingsway, B.C.), his party’s health critic, to announce the parties had reached an agreement on pharmacare, one day before their March 1 deadline to table a bill. That was an extension from the original Dec. 31, 2023, deadline set out in the supply-and-confidence agreement between the two parties.

In his opening remarks describing the bill, Holland focused on plans to implement universal coverage—a key criteria the New Democrats had for supporting the plan. However, when pressed by reporters, Holland was more equivocal about universality beyond the program’s first phase, which will see the government roll out single-payer coverage for diabetes medication and contraceptives.

Holland described this phase as “a pilot” and a “proof of concept” to be evaluated, while also pointing to a coverage model used in Prince Edward Island, which has a fill-in-the-gaps program that he described as “a different approach” that should also be evaluated.

Holland also had minimal details to offer about the costs of the initial phase of the program.

He first indicated that he did not expect there to be any costs in this fiscal year, but when pushed by reporters if that meant no one would receive medications under the program this year, he said his goal was to get deals signed as quickly as possible, so there may be some expenses.

Regarding the cost if the program were to be rolled out in all provinces, Holland first said that he would get back to reporters about that, then said “I do have a quantum in my head,” and finally, in response to a fifth consecutive question on the matter, said it may be roughly about $1.5-billion.

Rosalie Wyonch, a senior policy analyst at the C.D. Howe Institute who leads its health policy council, told The Hill Times she questioned whether the figure quoted by Holland could deliver coverage of diabetes medications and contraceptives for Canadians without needing a significant contribution from the provinces.

According to Wynoch, “$1.5-billion, as a speculative number, is interesting because just on diabetes drugs alone, public and private insurance [as of 2021] spends about $3.3-billion … and Canadians paid an additional $500-million out of pocket.”

She said, based on those numbers, the federal government would need the provinces to put up about half of the money for diabetes medication, even before addressing the cost of contraceptives.

“I think it’s highly optimistic that they think that the provinces will agree to expanding pharmacare coverage when they are going to have to shoulder the majority of costs,” said Wyonch. “The federal government might find that they need to provide more of an incentive to get cooperation.”

Intergovernmental Affairs’ staff ‘must be looking for a break’: Breton

Several policy experts interviewed by The Hill Times described the legislation that accompanied the announcement as also being sparse on detail, and said that means much is being left up to future negotiations with the provinces.

Michael Law, a professor at the University of British Columbia School of Population and Public Health, who holds a Canada Research Chair in Access to Medicines, said this means a well-entrenched universal system is not yet ensured.

“There’s still a lot of outstanding details that will matter here,” said Law. “A lot of how well this functions and how co-ordinated and consistent this is across the country will depend on the degree to which those negotiations are successful.”

Law said that programs that already exist in some provinces, particularly British Columbia, will give the federal government a jumping off point to get some of the deals in place.

“Politically, B.C. is going to be the low-hanging fruit here because B..C already funds contraception universally for the entire population,” said Law. “And B.C. also has expanded coverage recently for diabetes devices. So there’s clearly an interest there.”

That means British Columbia has the opportunity to access federal funding for a program it already delivers, making for an appealing offer. However, in provinces such as Ontario where a new program expenditure would be necessary, it might not be an easy sell, Law said.

Charles Breton, executive director of the Centre of Excellence on the Canadian Federation at the Institute for Research on Public Policy, told The Hill Times that the high volume of ongoing federal-provincial negotiations on multiple policy files—including several other sets of bilateral deals related to health care—could make completing pharmacare agreements more challenging.

“They’re busy,” said Breton of the staff working in Intergovernmental Affairs. “These people must be looking for a break.”

He said that same challenge is at play in the provincial governments, especially ones that tend to be more reluctant to make such deals with Ottawa.

“We haven’t heard Alberta complain about the health care deal … They were very quiet,” said Breton regarding the series of bilateral agreements Ottawa began last year on health care funding, for which Alberta was one of the first provinces to sign on.

Breton said it might be difficult for some provinces to sustain that approach over multiple bilateral agreements, and they might eventually say “‘we can sign one deal or two deals, but at some point these are provincial jurisdictions.’”

Fred Horne, a former Progressive Conservative health minister in Alberta, told The Hill Times that if he held the role today, one of the first items he would be looking at is how implementing such a program would affect individuals with private drug coverage. He said some provinces may also look at whether the program aligns with the areas they are want to focus their health care spending, saying that he would rather see an emphasis placed on rare diseases.

“We have legislation that’s been rolled out prior to achieving that broader consensus across the country,” said Horne, who is now a senior fellow at the C.D. Howe Institute.

Breton said some of these factors—like the need for the provinces to consult a wide array of stakeholders, such a private insurers—will make negotiating these agreements more challenging than the bilateral childcare deals, where Ottawa was able to build some momentum by starting with provinces that were most keen on the program.

Law said he is concerned some of these challenges may keep some deals from getting done, or produce a patchwork of dissimilar deals across the country, making the program more vulnerable to reversal by a future federal government.

“It would leave any resulting federal program very vulnerable to just being killed by a government that wasn’t in favour of it,” said Law. “A government could get elected and say, ‘Now we’re just going to add this to the Canada Health Transfer, wipe our hands of it, and no more national pharmacare.’”

icampbell@hilltimes.com

The Hill Times

LICENSING

LICENSING PODCAST

PODCAST ALERTS

ALERTS